Two are yellow, two are orange, two are the shade of sunglasses, and at 4 by 4 feet, the new solar windows in the entryway of the Western Gallery are the largest of their kind ever installed.

They’re an accomplishment for Western, a landmark in a 12-year-old research effort involving faculty, students in several departments and a partnership with private industry. But more than that, they represent the beginning of a technology that could help free cities from dependence upon fossil fuels.

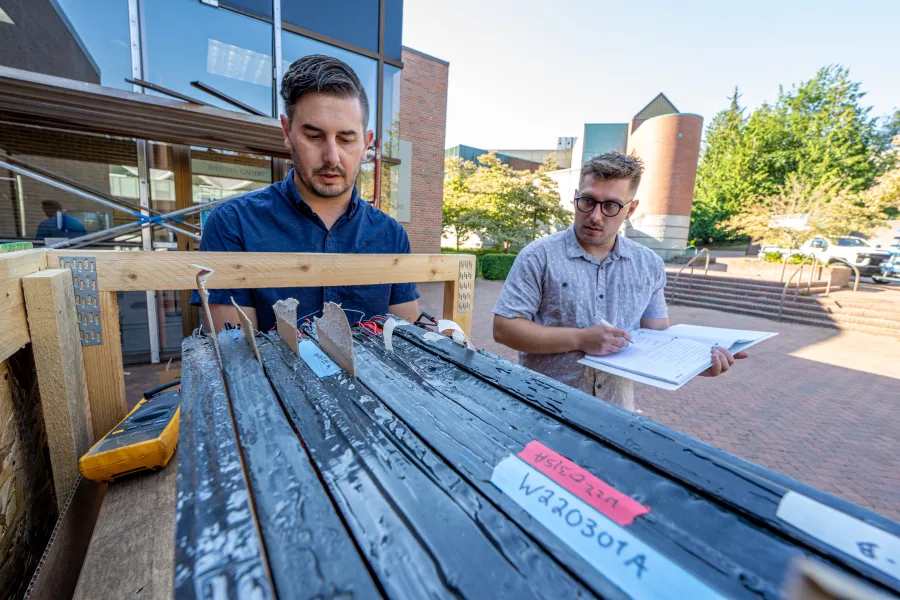

Daniel Korus, ’19, B.S, and ’21, M.S., chemistry, and Matt Bergren put the final polish on the six new solar windows on July 29.

Bergren is chief product officer and Korus is the windows project manager at UbiQD, the Los Alamos, New Mexico-based company that built the windows. The name UbiQD stands for “ubiquitous quantum dots” and the company is developing a window technology brand called "WENDOW," where the "EN" stands for energy. Western and UbiQD collaborated to pay for the windows.

In each window, two layers of glass sandwich a layer of plastic containing microscopic nanoparticles of a special kind of pigment. The particles absorb sunlight and glows a particular color. Called quantum dots, these special dye particles can be designated to glow orange, red, or near-infrared, which makes them appear brown-ish. The plastic layer guides that light to tiny solar panels at the edge of the window, producing electricity.

A team of researchers from WWU and the University of Washington patented a method of harvesting solar energy using these pigments, and in 2017, UbiQD exclusively licensed the patents.

Korus’s work with the windows goes back to 2018, first as an undergraduate and later as a graduate student, in the chemistry lab of David Patrick, who is now Western’s vice provost for Research and dean of the Graduate School.

Korus arrived at Western after struggling with chemistry in high school in Spokane.

“I was so bad that my teacher had my dad do a lunchtime conference with me, him and the teacher to tell him that I wasn’t fit for science, that I should not do an AP class, nor should I continue in chemistry.”

For the record, Korus’s dad did not believe that teacher. And once Korus came to Western, he found that what he enjoyed most was chemistry lab work—hands-on tasks such as extracting caffeine from tea leaves. He took up research because his friends were doing it, and he didn’t want to be left behind, he says. When he started in the lab as a junior, he had a packed schedule: along with classes, he was doing two workouts a day as a member of the rowing team, and held a part time job leading tours at the admissions office.

But Korus enjoyed being part of a team of undergraduates and graduate students.

“They were showing me the ropes. I was learning from the students next to me how to do lab work.”

While some labs work like factories, with students each focusing on a particular task, the students at the Patrick lab participated in all aspects of the projects.

“It was everything from wet chemistry through to the device stage, and then we’d go measure the device ourselves, usually.”

He said Patrick’s lab struck a great balance for an undergraduate: There was enough freedom that he always felt ownership of his work, but enough support that he never felt lost.

And although he looked into other graduate programs, he didn’t encounter a supervisor he liked as much as Patrick, or a project as compelling as solar windows.

He stayed on for a master’s degree, which he ended up finishing while working at UbiQD.

Korus has seen the technology improve rapidly.

When Korus started working on windows, the largest most anyone could produce was 3 inches square. The engineers at UbiQD changed that.

Professor Stephen McDowall, a mathematician, has been a point of communication with UbiQD and watched the progress. “We make these little sample sizes,” he says. “They make them in these huge vats (of dye) with big buckets at a time. It’s just a different scale.”

The windows’ journey to Western had its challenges, Korus says.

“There are three sighs of relief. The first is when they get there and they’re unharmed. The second is when they fit.”

The windows fit, and a crew was able to install them just as if they had been made of regular glass. One pane cracked under a glazier’s hammer, but they had a spare.

Which brought them to the third sigh of relief: seeing the windows generate their first electricity.

Work on the windows goes back to 2010, when a group of faculty from Western’s Advanced Materials Science and Engineering center won a grant from the National Science Foundation. At the time, they did not foresee how successful it would be, Patrick says.

“It was fundamental, basic research—blue sky stuff—and sometimes that works out and sometimes it doesn’t.”

From the beginning, the drive involved collaboration.

The initial grant went to two chemists: Patrick, and Professor John Gilbertson, two physicists: Brad Johnson, now Western’s provost, and Janelle Leger, now dean of the College of Science and Engineering, and a mathematician, McDowall. Eventually, business and industrial design students got involved, too. In 2015, a team of chemistry, engineering, industrial design and business students won a $75,000 P3 award from the Environmental Protection Agency to continue work on the project and investigate potential commercial concepts. Through business plan competitions and public presentations, their work helped draw attention to the new technology and attract industry interest.

“Now the arts are getting involved, too. How wonderful is that?” Patrick says.

Hafthor Yngvason, director of the Western Gallery, was eager for the new windows.

“I found it really quite exciting for two reasons. This was a scientific experiment right here in the entrance way to the gallery, and also to do something interesting with this glass cube that we have, which is the entrance to the gallery, and right now it is not visually interesting.” Associate Professor of Design Paula Airth came up with the arrangement of the six windows. If things go well, Yngvason would love to see the whole cube covered in colorful solar windows.

“I like it when art and science come together this way,” he says.

For now, the electricity from the windows is dedicated to collecting the data on how much energy they generate day-to-day. There’s a lot Korus and Bergren need to find out about how the windows perform.

Not only are the Western Gallery windows the biggest UbiQD has installed, they are the only ones outside the southwest U.S. And sunshine in Bellingham works a little differently.

In one way, the conditions are better. Because sunlight strikes us at a lower angle this far north, a vertical surface might be able to collect more light, Bergren says. But then, there’s less sunlight to be had. Winter days are short, and clouds, fog, and rain are the norm. Bellingham gets an average of 157 sunny days a year, while Los Alamos gets 276.

The windows in the Western Gallery have visible wires coming from them, but Bergren says it is possible to run the wires through the window frames, so that to most observers the windows don’t look any different from regular glass, at least to humans.

When the data gathering is over, and UbiQD no longer needs the windows’ electricity for science, then it might power art at the Western Gallery. One possible future recipient: Sound Out Radio, which will broadcast from a pair of metal structures Assistant Sculpture Professor Sasha Petrenko is installing on the roof of the cube. The student-run radio station will broadcast from the roof intermittently and eclectically.

“I know we need to have it on in the middle of the night on Fridays because one of my students wants to make a radio show specifically for nocturnal animals,” Petrenko says.

It’ll start off powered by the regular electric grid, Yngvason says, but maybe in the future solar windows could power the creative broadcasts.

As Korus and Bergren worked on the windows, they attracted a stream of visitors, including Patrick, Korus’s mentor.

“He had a pretty big smile on his face,” Bergren says. “Watching Daniel and David give a hug and a high five, it was a moment.”

It was a great feeling to see the new glass in an actual building, Patrick says.

“It was exciting and satisfying both as a scientist and as a teacher, as a mentor, as a faculty member. Dozens and dozens of students over the years engaged in that research and moved it forward.”

For McDowall, the colorful panes are a reminder of the caliber of research Western does with undergraduates and master’s students.

“That’s pretty unique among universities for students at such an early stage to get involved doing research like this,” McDowall says.

Korus hopes the colorful panes in the cube will serve as inspiration to undergraduates to get involved in research projects.

“In their undergraduate research they can take the things they learn and the experiences they have and go do something meaningful with it.”

Korus hopes to be back making more solar window installations at Western before too long.

UbiQD plans to test the windows in different locations and climates, all while coming up with ways to make it easier to manufacture them at large scale, Korus says.

The company’s goal is to have windows that generate 50 watts per square meter, about one quarter to one third the rate of current solar panels, Bergren says. It’s not the whole solution to freeing urban environments from fossil fuel dependence, but combined with other strategies to conserve energy and shift to renewable sources, solar window ubiquity could make a better world.

“I want the windows to be so widespread that, you know, I go to the dentist and I see one of our solar windows,” Korus says.