You can’t miss it, really. The sculpture rises from Red Square and surrounding academic buildings of similar color and conservative design, like an alien object dropped from outer space.

Perched on stubby pillars, the 14-foot-high cube with circular spaces seems to defy gravity with a delicate three-point stance, a ballet dancer floating en pointe a foot above the square’s brick walkway.

Isamu Noguchi’s “Skyviewing Sculpture,” one of campus’s oldest and most famous pieces in a renowned outdoor sculpture collection, is about to star in its own show. “Looking Up: The Skyviewing Sculptures of Isamu Noguchi” is set for July 26-Nov. 26 at Western Gallery on campus. Skyviewing was a recurrent theme in Noguchi’s career that spanned six decades, from the mid-1920s until his death in 1988.

But this is the first time Noguchi’s skyviewing works, about 40 in total loaned from the Noguchi Museum in New York, have been gathered and shown. According to the exhibit’s description, items in the collection act as “observatories, reflecting telescopes, or sundials (to) mirror the firmament, trace the path of the sun with cast shadows or lead the eye up toward the sky.”

Observatory for the naked eye

On campus, “Skyviewing Sculpture” serves as a naked-eye observatory. Made of painted iron plate, it tilts precisely to accomplish Noguchi’s intent to create frames for the sky. Western Gallery Director Hafthor Yngvason had intended the exhibit for the sculpture’s 50th anniversary in 2019 before being stymied first by lack of funds, then the Covid-19 pandemic. Yngvason, responsible for bringing the exhibit to Western, also edited a book, “Looking Up,” which will be published in time for the event. Lead sponsorship for both the exhibition and the book is provided by the Henry Luce Foundation, with additional funding from the National Endowment for the Arts.

When Yngvason brings students to study the sculpture, he first has them stop about 75 yards away. From a distance, it’s a simple cube. Get closer, and Skyviewing practically begs you to come inside. You duck in, and that’s where Noguchi’s magic is revealed.

“We go inside it and it’s a completely different shape,” Yngvason says. “After the transformation, you’re suddenly in a different space. And then, the way it’s designed, the eye is just drawn up.”

Inside, unexpectedly graceful curves and angles, a complex geometry, run counter to the work’s uncomplicated exterior. But Noguchi wants you to look up: You see sky blue framed through one space, sections of buildings and sky through another. You see treetops and clouds. Birds zip past.

Yngvason once visited the cube one night in three consecutive months to capture the full moon through the yawning round portals. The match-up was no accident. Noguchi “was absolutely in control of exactly where it was,” Yngvason says.

Students have noted the sculpture’s resemblance to Darth Vader. Except this Darth Vader has an inner lightness. And by design, you don’t need a ticket to experience it.

“He gave the entire student body an observatory that everyone had access to,” says Dakin Hart, senior curator at New York’s Noguchi Museum.

Japanese American Noguchi was a seminal figure in the art world and beyond with his multicultural background foundational to his work. Noguchi also helped transform how the public viewed art by bringing it to shared public spaces, rather than restricted to galleries and indoors. Noguchi designed playgrounds, landscapes, and even furniture.

“In the creation and existence of a sculpture, individual possession seems less significant than public enjoyment,” Noguchi says in Yngvason’s book intro.

Plaza, piazza

“Skyviewing Sculpture” didn’t make Noguchi more famous. Just more fulfilled.

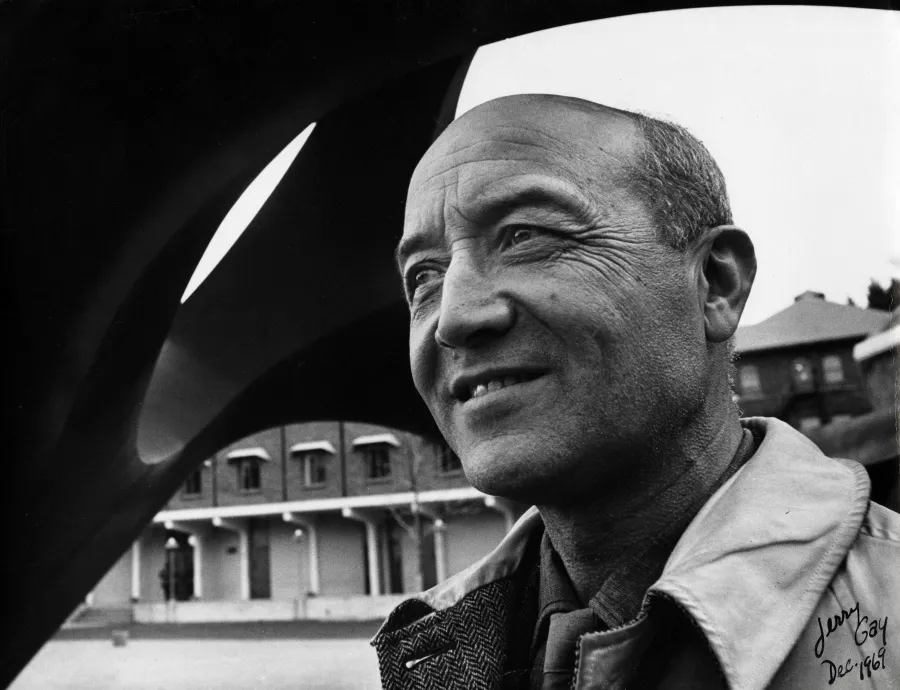

At the time of the sculpture’s December 1969 installation, Noguchi was 65 and in the prime of a prodigious career. He had a major retrospective at New York’s Whitney Museum and his autobiography was recently published. He had just unveiled two big public pieces in Seattle’s Asian Art Museum’s “Black Sun” and “Red Cube” in Manhattan.

At that point in his career, Noguchi “did the jobs that he was excited about, he didn't care if anybody else knew about him, and he didn’t care if he even got paid for them,” Hart says.

Noguchi loved the idea of Italy’s piazzas, a space for public buildings religious and civic, commerce, private residences, and people conducting daily life. “That was his idea of great sculpture,” says Hart. An American university campus, says Hart, is closer to an Italian piazza model than almost any other kind of town square.

“I think he was just incredibly excited by Red Square,” Hart says. “(Skyviewing is) one of his very best pieces, most truly site-specific pieces, because here he is in the equivalent of an Italian piazza… it was really an ideal location and an ideal commission. And I think he hit it out of the park.”

Born in 1904 to acclaimed Japanese poet Yone Noguchi and U.S. writer and editor Leonie Gilmour, Isamu Noguchi grew up in Japan and the U.S., and traveled extensively. Besides his sculpture and public art, Noguchi designed modern furniture, including the ubiquitous Akari light sculptures and an iconic coffee table. He created stage sets for famed choreographer Martha Graham, the original baby monitor, and playgrounds and gardens. Though critically acclaimed, he had to support himself by sculpting portrait busts before finding fame later in life.

Noguchi was ahead of his time, fascinated by space and the cosmos long before people walked on the moon (just months before Skyviewing landed at Western). In the late 1920s at a Greenwich Village café in New York City, Noguchi met architect, author and philosopher Buckminster Fuller, who popularized the geodesic dome and became a mentor to Noguchi. At the time, “there were very few people on the planet who were capable of thinking of the Earth as a big round rock floating around in space,” says Hart. “Bucky was one of them.”

Fuller was the guide for what would become Noguchi’s world view. The history of looking up, says Hart, is “the history of looking to the stars, the history of looking to God or the gods, whatever it may be out there. It’s the history of the development of the natural sciences and of a lot of philosophy. It still undergirds a lot of philosophy, and astronomy. It’s where the hard sciences and ontology come together. That was a really happy place for Noguchi. He spent a lot of time there, and he made a lot of work that relates in one way or another, to this metaphorical activity, of looking out into space.”

Noguchi’s faith that technology and humankind could produce great things was crushed by World War II, the Manhattan Project and America’s incarceration of Japanese American citizens. (Noguchi lived outside the exclusion zone, but, in protest, was voluntarily locked up for seven months in a prison camp in Arizona.) Then came the NASA space program to restore Noguchi’s optimism.

New York’s Noguchi came to the Pacific Northwest by virtue of his connection to Buckminster Fuller. Seattle architect Ibsen Nelson, who redesigned Red Square, headed the Seattle Arts Commission in 1965 and spearheaded efforts to bring Noguchi’s “Black Sun” sculpture to Seattle, aided by Fuller’s second cousin, Richard Fuller, founder of the Seattle Asian Art Museum. Nelson then brought Noguchi to Western Washington University.

Noguchi’s influence a legacy

Fred Wilson, a conceptual artist whose themes of race and cultural origin helped him achieve current acclaim and a 1999 MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant, holds Noguchi as both an inspiration and major influence. In November 2021, Wilson cited Noguchi while selecting the location of his chandelier sculptures now hanging in Viking Union, a five-minute walk from Red Square and Skyviewing.

Wilson’s two Murano glass chandeliers, “A Moth of Peace,” and “The Way the Moon’s in Love with the Dark,” one of white glass, the other black and modeled in traditional Venetian and Ottoman styles, seek to examine how cultures interconnect through exploitation, oppression, trade routes and imperialism.

When Wilson was the lone Black student in Purchase College’s Bachelor of Fine Arts program in the 1970s, Noguchi “was the only person of color I ever knew at that point who had any visibility. He was the only one I’d ever heard of.”

Much of Wilson’s work focuses on the neglected history of Africans and African-Americans. His installations and sculptures explore and challenge racism in colonial legacies and even in places like museum collections and display language.

“(Noguchi’s) fearlessness of making functional art, functional objects—it’s all embedded in the culture that his father’s side came from,” Wilson says. “It was extremely enlightening to me. Because there was no one else. His work spoke to me the way no one else in the place that I was going to school could. You know, they just didn’t have that personal, authentic experience.”

With skyviewing, like much else in his life, Noguchi saw the big picture and wanted to it to be shared. Hart posits that Noguchi’s influence may never have been stronger than right now. Biracial, multicultural with a complex identity, Noguchi was—as when he first looked to the stars—ahead of his time.

“Now, many artists and designers and other creative people in many different disciplines recognize him as a kind of, as an avatar, as an exemplar, as a model, as a role model,” Hart says. “He was somebody who in a very respectful, deep-connected way, was interested in looking to universals and looking for the things that unite us as human beings, not separate us.

“He never compromised on doing all the different kinds of things that he wanted to do…Now, contemporary art is opened up so much. It’s so much more open-ended. And artists are able to do whatever they want and call it their art form. And the world accepts that much more readily than it used to. That is in large part thanks to the example of people like Noguchi.”