Mighty Women of Western

In the late winter of 2013, Western Washington University’s athletic department faced a dilemma of the good kind. Both women’s and men’s basketball teams had earned the chance to host the NCAA Division II regional tournament, a huge advantage in advancing to the NCAA Final Four, and possibly the national championship.

Schools rarely qualify to host both; doing so would create a logistical tangle for the NCAA, which apparently likes a measure of control over its March Madness. Their unwritten rule: A school could host only one regional. The assumption was Western would choose to host the men, because that’s how it traditionally went—along with the fact that the men’s team was the defending national champion, after winning the program’s first title in 2012.

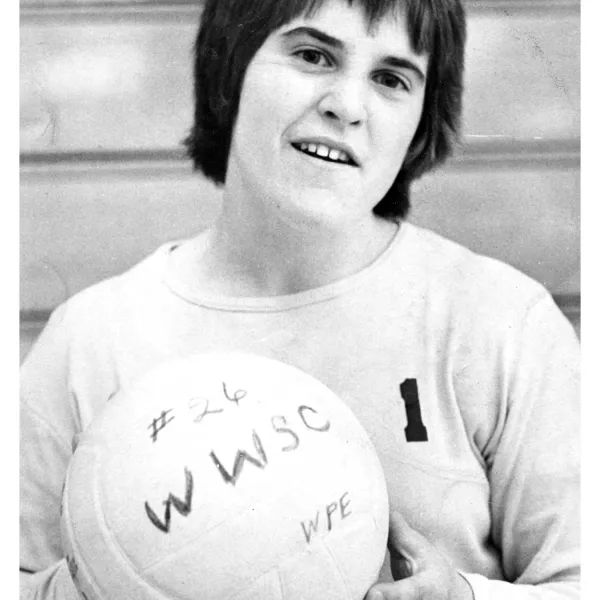

Western’s veteran women’s coach Carmen Dolfo, ’88, BAE, physical education and recreation and ’99, M.Ed., student personnel administration, braced for a fight, preparing a mental list of arguments why her team should host. “I’m sure Tony was doing the same,” Dolfo says of the men’s head coach Tony Dominguez, ’94, B.A., communication, in his first year as head coach after being a longtime assistant under Brad Jackson. Western Athletic Director Lynda Goodrich surprised them both. “We’re going to flip a coin,” she said.

Dominguez called it; Dolfo won.

Goodrich, ’66, BAE, physical education and special education, and ’73, M.Ed., physical education, contacted the NCAA with the news that the women’s team would host. The NCAA “was in shock,” Dolfo says. You’re picking the women’s team over the men? Goodrich, a national Hall of Fame athletic director and coach, stood her ground. Not only that, she eventually managed to convince the NCAA to allow both teams to host at Western after all.

“They just couldn’t see not allowing the men to host,” Dolfo says. “And so we both got to host. It was a fabulous weekend.”

Both teams ended up winning their tournaments and advancing to the Final Four that year. Goodrich, says Dolfo, believes to this day had she simply picked the men, the women would have been sent elsewhere, losing precious homecourt advantage and exposure. “I thought that was a pretty cool example of (Goodrich) doing what was right instead of what was easy.”

WWU Women's Athletic History

Eleven of Western’s 12 national championships have been won by women’s teams. And women brought home 26 of the 34 individual national championships. See them all.

A tradition of powerful women

For Goodrich, it wasn’t unusual to put women on equal footing. Well before Title IX, Western was ahead of the game when it came to women and athletics.

Even before Goodrich became the rare female athletic director for both men’s and women’s teams in 1987, she was continuing a legacy set by Western’s physical education and coaching trailblazers like Margaret Aitken, Chappelle Arnett and Evelyn Ames.

Viking icons whose careers together span nearly six decades, Aitken, Arnett and Ames were physical education professors who also coached women in an era when women’s teams were afterthoughts. The three were early believers in the value of athletics for women, even if the powers-that-be didn’t share that belief.

Aitken, who taught at Western from 1946 to ’84, was a badminton expert and tennis coach for whom Western’s tennis courts are named. During her time at Western from 1964 to 2003, Ames coached a variety of sports, including basketball—even when women were not allowed to run full court because it was perceived dangerous for them.

During her career at Western from 1960 to 1990, Arnett coached field hockey early on and was at the forefront in the emerging field of exercise science, securing federal grants for things like the first stress-testing treadmill on campus and establishing a small lab above the swimming pool.

All three women were all part of a transition in the physical education department from skills-based teaching to science-based movement and, eventually, kinesiology.

“I really respected them,” says Goodrich. “You kind of want to be like them, you know? You know how it is when you have teachers that are really good.” Plus, “Margaret and Chapelle and Evelyn—they went to bat for things. And of course, I did too.”

In 1972, the year Title IX passed, Aitken had become the surprise chairwoman of a newly combined men’s and women’s Physical Education Department, one of the first women in the nation to hold that title. The men’s department had split their vote for the new chair while the women backed Aitken. One consequence: The athletic director now reported to her, a development that caused the AD at the time to quit in a huff at year’s end.

Steve Chronister, ’78, BAE, physical education, now in his 45th year coaching and teaching in Bellingham Public Schools, was a student of that era. He says students knew they were seeing a foundational shift at Western that wasn’t necessarily happening on other campuses.

“They held significant positions,” he says of the women. “They were agents of change. I’m 20 years old, 21 years old, but at that time, that was real change. It was not something that went smoothly, necessarily.”

When Goodrich, a successful women’s basketball coach and athletic director for women, was approached by Western President G. Robert Ross to take over the vacant athletic director’s position in 1987, leading both men’s and women’s athletics, she said no. “I’m not a Margaret Aitken,” she said. “I’m not going to be a pioneer. I know what she went through.

Ross hadn’t even launched a search, Goodrich says. “He said, ‘You can do it, and I’ll support you.’ And so I did it.”

Later that year, Ross was killed in a plane crash. Without Ross to back her, Goodrich decided to resign the AD position. But at his memorial service, Ross’s wife hugged her and drew her close. “She whispered in my ear and said, ‘You do a great job and kick ass. Bob had a lot of faith in you.’ And I thought, ‘OK. I’ve got to keep doing this.’ And it worked out OK.”

Title IX 50th Anniversary Celebration

Western’s Back2Bellingham weekend will include a long overdue presentation of varsity letters to WWU women athletes from 1968 to 1981. If you or someone you know is eligible for this award, contact Nicole Ebersole at Nicole.Ebersole@wwu.edu or 360-650-3997.

A vision without limits

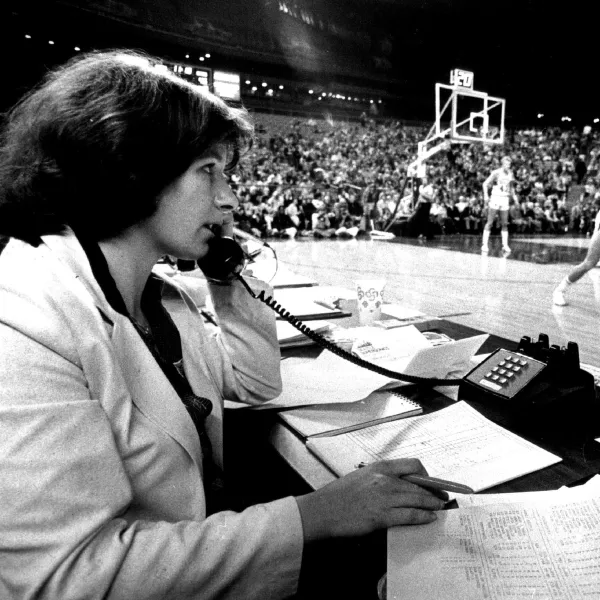

A turning point was women’s basketball’s first game in Carver Gym in March 1973. Before that, the women’s games and practices had been relegated to Gym D, a 1930s relic where limited space under the basket restricted drills and the stands held only 1,400 spectators. Carver’s main gymnasium, built in 1961, held more than twice that. About 1,800 fans came to watch Western beat rival Washington State in a 48-46 thriller for the regional championship that sent the Vikings to the national tournament for the first time.

“It was just an unbelievable game, tight all the way through,” says Western athletics historian Paul Madison, ’71, B.A., journalism. “People were there and loud and going crazy.”

Madison’s game story appeared in the next day’s Bellingham Herald, the first time a Western women’s sporting event had received more than a short paragraph in the paper.

Like the women before her, Goodrich was a conduit to those who followed. Sherry Stripling, ’75, B.A., journalism, who went on to become the first female sportswriter at The Seattle Times, was on that basketball team.

“I would like to be able to say that the first game in Carver Gym was a huge turning point but to me it just felt like a natural next step,” Stripling says. “Lynda had no limitations in her vision of what we could accomplish, and I think to win we had to believe that was true, too.”

Supporting the Next Generation

A new scholarship endowment has been created by former Viking female athletes to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Title IX. The Honoring Women in Sport and the Historic Impact of Title IX Endowment will fund scholarships for members of WWU varsity women’s athletic teams.

Video by Sean Curtis Patrick and Luke Hollister