A weeklong workshop the summer before Terri McMahan’s senior year at Western changed her life. Taught by physical education professor and visionary Chappelle Arnett, the 20-hour workshop was about Title IX, the landmark law signed a few years earlier by President Richard Nixon as part of the Education Amendments of 1972.

The summer workshop “was a defining moment for my future,” says McMahan, ’77, BAE, and ’80, M.Ed. “We knew that Title IX was monumental, but we didn’t know just how monumental. I’m in my early 20s, and I just didn’t have that vision. But Chappelle did, and she talked to us about a future that she knew we couldn’t imagine.”

Title IX, which turned 50 in June 2022, consists of just 37 words: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Its effect on education and athletics would be seismic. Originally designed to address discrimination affecting women in graduate and law schools, it came about at a time when graduate schools openly discriminated against women, in some cases accepting limited numbers of female applicants, requiring higher grades than men and restricting what women could study. In 1970, 34% of women in the U.S. labor force did not have a high school degree, and only 11% had a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The law does not include a single word about athletics. Yet its effect on sports would be far-reaching and lifechanging— from participation to budgets to careers for women and girls.

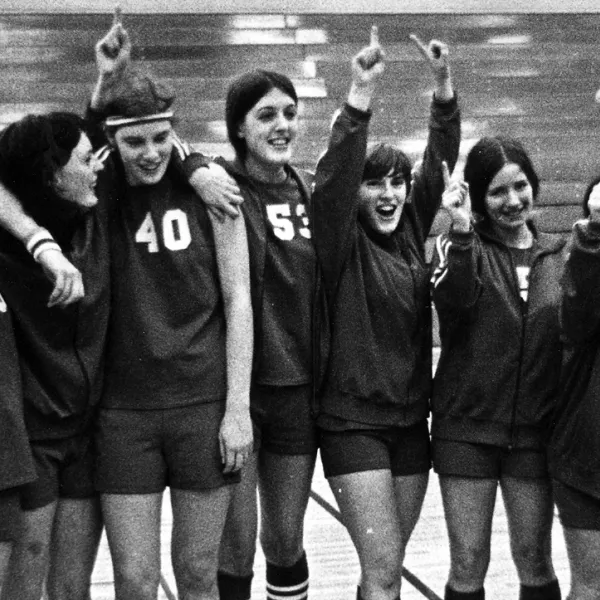

In 1972, about 294,000 high school girls participated in athletics compared to more than 3.4 million by 2018- 19, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations. Fewer than 30,000 women played collegiate sports prior to Title IX; more than 219,000 played in 2020-21.

Yes, there has been staggering success. But Title IX, a half-century later, in some ways has not fulfilled its promise of an equal playing field. Schools continue to fall short of compliance and most avoid punishment, with the exception of occasional lawsuits. In 1979, Washington State University was successfully sued by students and coaches, setting a precedent for the state’s public four-year institutions.

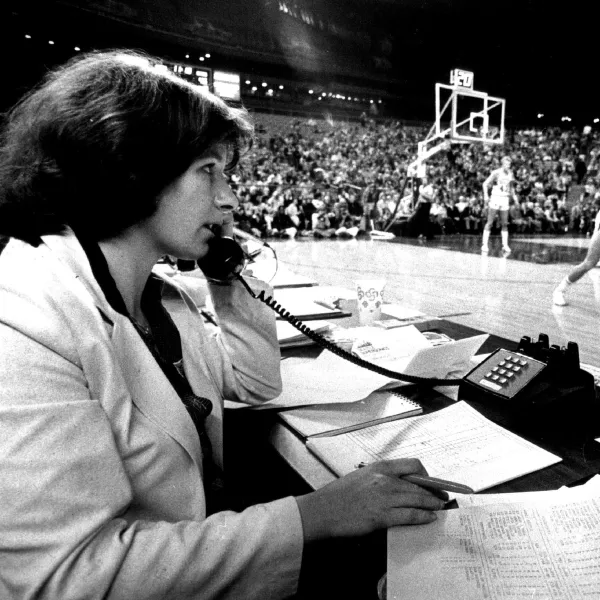

Progress has been slow. Title IX’s passing in 1972 didn’t mean women’s athletic departments were suddenly flush with money. It wasn’t until 1989 that the state authorized the use of tuition waivers for four-year public universities. Western athletic director Lynda Goodrich, ’66, BAE, and ’73, M.Ed., along with a representative of Washington State University and state Sen. Ken Jacobsen, testified before the Legislature to grant the waivers, funding a steady stream of athletic scholarships. “That really helped take women’s athletics to another level,” Goodrich says.

Public opinion can be justifiably withering too, when universities fall short in preventing discrimination on the basis of sex. Consider the case of the 2021 NCAA basketball tournament, where University of Oregon player Sedona Prince’s TikTok video went viral comparing women’s and men’s weight rooms, shaming the NCAA.

In Title IX’s early days, alarmists feared gender equity would kill men’s sports funding. It didn’t, but the law has been blamed by university presidents and athletic administrators as the reason for cutting non-revenue men’s programs. The reality: It’s not Title IX. Men’s and women’s non-revenue sports both suffer from schools’ outsized emphasis on high-profile programs like football and basketball.

One of Title IX’s latest issues: Transgender female athletes use the law to back their civil right to play on women’s teams. Meanwhile, some cisgender women athletes use Title IX to say they are at a disadvantage competing against trans women. As of mid-2022, 18 states had laws banning transgender students from participating in sports matching their gender identity.

Outside of sports, Title IX provides protection when it comes to sexual misconduct in schools and on campuses on the basis that victims are deprived of equal access to an education, creating additional legal urgency for universities to address the devastating problem of sexual violence on campus.

While it doesn’t erase gender inequality, Title IX’s impact has been far-reaching. From girls playing in Little League baseball to women’s professional leagues in basketball and soccer experiencing an explosion in popularity and market appeal, Title IX is deserving of all its celebrity as it turns 50.

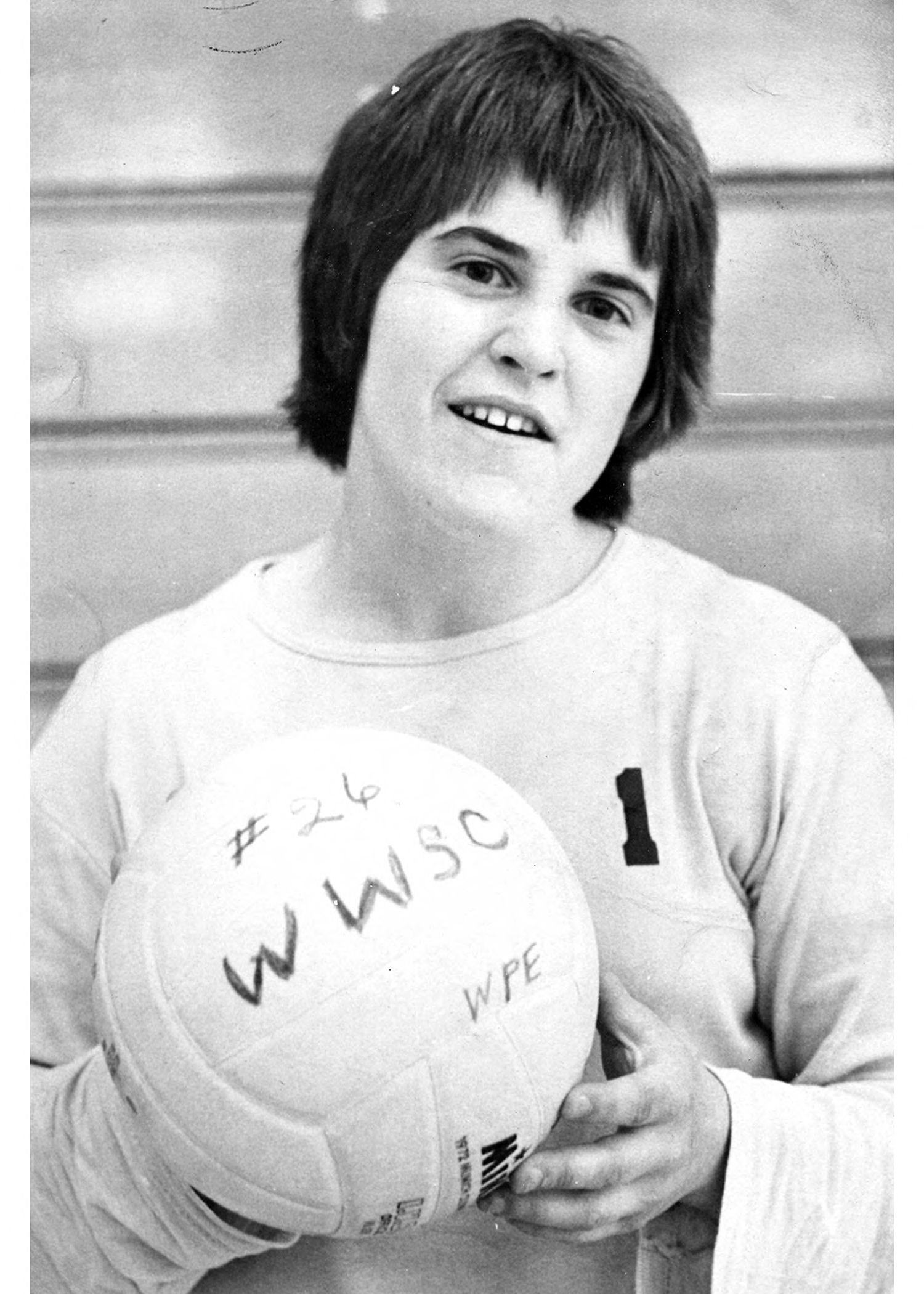

People like McMahan, who loved playing and coaching sports, found a world opening to them that had not existed. A top Western volleyball player, McMahan became a high school Hall of Fame coach and athletic director. Hired as a teacher and coach at football-intensive Ferndale High School, she became Ferndale’s first female athletic director— the state’s first female AD north of Seattle, in fact—and later rose to lead the Edmonds School District and Highline Public Schools athletic departments. She and others of her time were models for generations to follow.

“I look at my career path and those of my colleagues as the first wave of women who had these opportunities,” McMahan says. “I will always give credit to Western for the opportunities I received. I was able to spend my entire career in athletics as a result, having not seen women in athletics administration while growing up. Today, young women aspire to be directors of athletics before even starting college because they grow up now seeing women in these roles.”