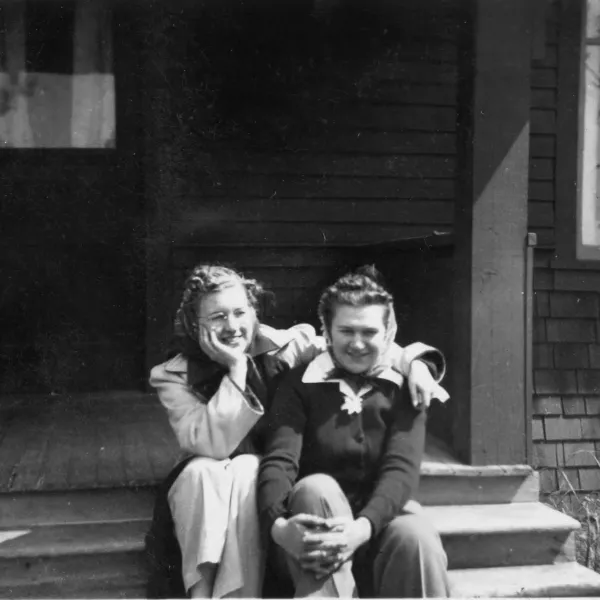

While East Coast universities established rivalries in women’s field hockey, many West Coast schools offered tamer competitive outlets for women from the late 1930s to 1950s in the form of Sports Days or Play Days that promoted the values of sportsmanship and friendship. Multiple schools would descend on one campus for a day of play and social activities, often on mixed teams rather than school vs. school.

Each student was “assigned” a visitor as she got off the bus, and the two would spend the day playing and socializing without the intense competition that was the hallmark of men’s sports.

Also not like the men: a beauty component. At Western, it would happen in Gym D, the main floor of the Physical Education Building, built in the 1930s and referred to as “the women’s gym.” For the “Posture Parade,” students from each team would wear high-heeled shoes and march around the gym while female faculty selected a champion based on what a woman was supposed to look like.

Before there were varsity sports for women at Western, there was the Kline Cup. The women’s basketball tournament in the early 1900s had class teams competing for a prestigious trophy sponsored by Valentine and Clarence Kline, brothers who owned a jewelry store on Bellingham’s West Holly Street.

Early basketball was the six-woman version with the court divvied up in thirds, no one allowed to run full-court and only two or three dribbles permitted per player – a holdover from Victorian-era beliefs when women were considered too delicate, or too constrained by corsets, to exert themselves.

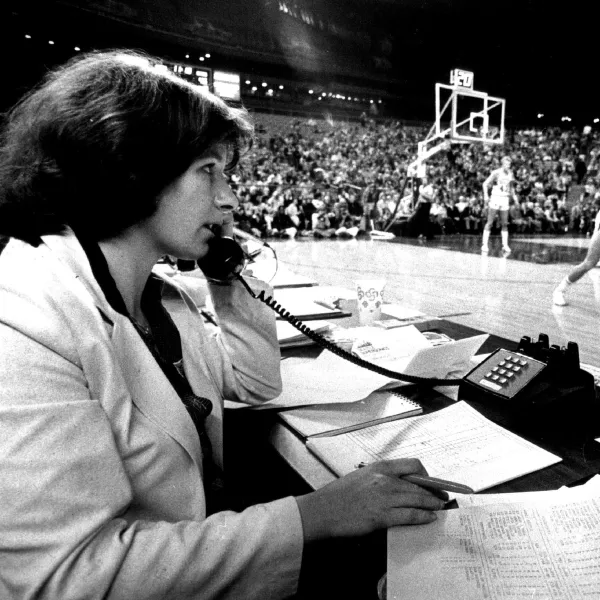

Women’s athletics competitions would evolve. Evelyn Ames, who taught in the Physical Education Department for nearly 40 years, coached basketball at Western from 1965-69. Western would host the University of Washington, Oregon, Washington State, Central Washington and Eastern Washington in annual school-vs.-school basketball competition.

“It would be over the course of about two or three days,” says Ames, who would sometimes coach and then officiate games, “and it would be finished with a banquet.”

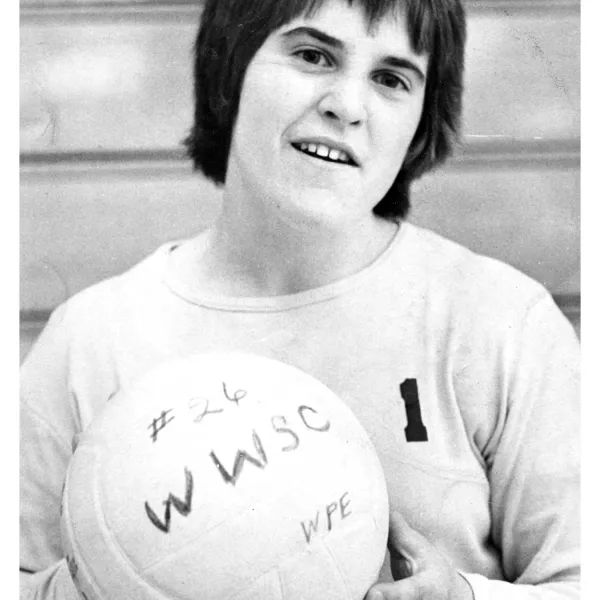

The game transformed with the introduction of the “rover” position – one player allowed to roam freely. One of Ames’ standout players: Lynda Goodrich, who would go on to be named Western athletic director and set the course for women, and athletics, for decades at Western. “She was my star forward,” Ames says. “She would not hesitate to shoot when she had an opening. She wanted to score.”