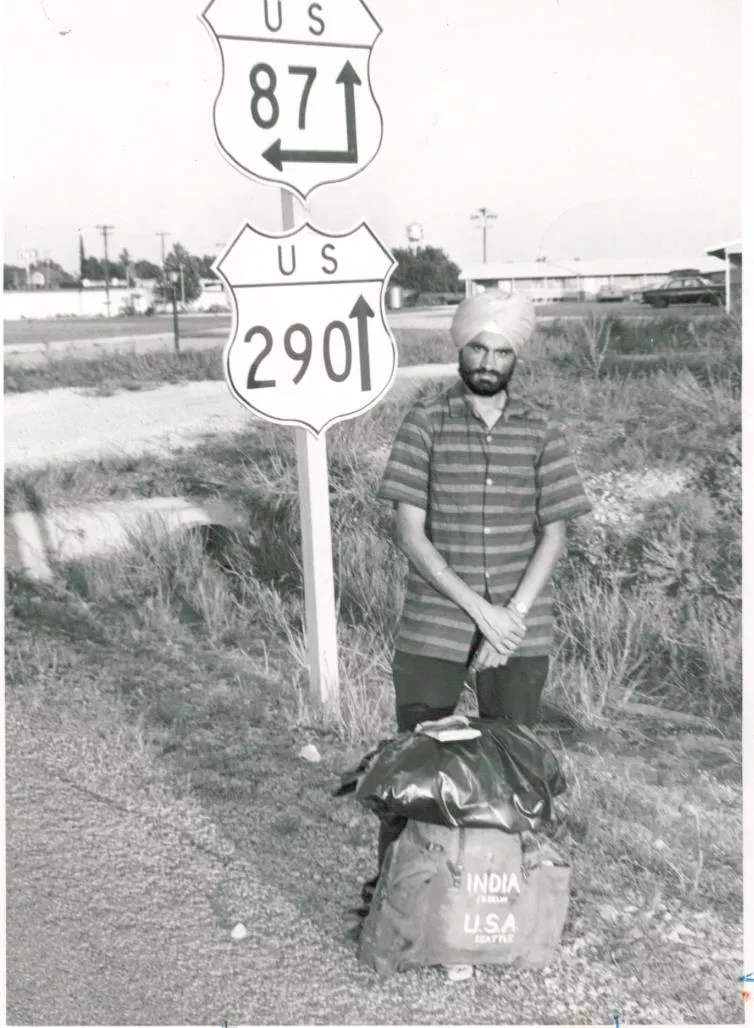

Deep in the vaults of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, you’ll find a very worn turban cover, along with a pair of black pants, a striped shirt and a tattered backpack stamped with “India N. Deli, U.S.A Seattle.”

What story is stitched and patched into that backpack? Whose turban did catalog number 2019.0073.4 protect?

These items belonged to educator Hardev Singh Shergill, ’62, M.Ed., who hitchhiked from New Delhi, India, to Seattle in 1960 before enrolling at Western. They’re part of a Smithsonian collection honoring the many ways immigrants arrived in the U.S.

Shergill’s story began in the northernmost corner of India, where he grew up in a village founded by his grandparents on the border with Pakistan in Bikaner State. He earned degrees in English, economics and geography at Panjab University and taught at a teacher’s college in Muktsar, Panjab.

But his ultimate goal was to travel the world, so he became a geography teacher at the Air Force Central School in New Delhi, where he could establish contacts with embassies. In 1960 he applied to the doctoral program in geography at the University of Washington, hoping for a new life in the U.S.

Shergill’s application was accepted, and his grandfather gave him $1,200 for the year. But Shergill didn’t want to spend the money on an airline ticket to Seattle, he wanted to have enough money to start his life there.

What better way to study geography than by traveling the globe?

He wrote some letters of introduction to relatives and family friends and gave a trunk full of his belongings to a friend to be shipped upon his arrival. He donned the shirt, pants, and turban cover that now reside in the Smithsonian, shouldered his pack, and began his journey by train from New Delhi in June 1960.

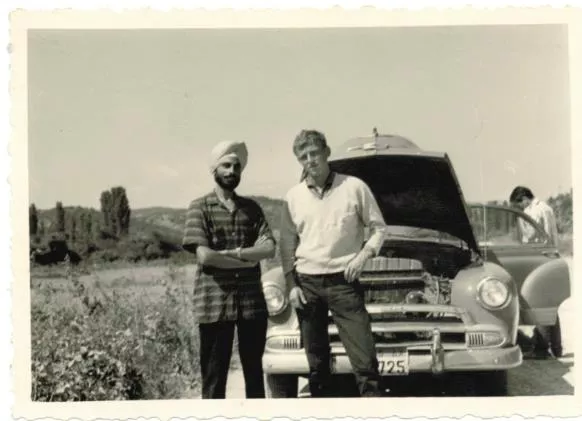

Seeing The Sights

In Pakistan and Iran, Shergill bunked with friends-of-friends and distant relatives, but once he arrived in Türkiye, he was on his own. Stringing together Indian embassies in several cities, cheap youth hostels, and the generosity of fellow Indian ex-patriates, Shergill managed his way across Türkiye, Greece, Yugoslavia, Austria, Germany, Paris, London and then Bristol, England, where he got free passage on an oil tanker to Baytown, Texas, thanks to the Indian Seamen’s Welfare Office.

The 16 1/2-day voyage across the Atlantic was difficult for Shergill—he suffered from seasickness and the endless, monotonous sea. For the first time in his journey, he was in low spirits, grieving his mother who had died four years before, and missing his siblings and cousins. But early the morning of Sept. 5, 1960, Florida came into view.

In his journal, Shergill writes, “And it is Mum now who comes most in my thoughts—how would she have felt, were she alive, when I left the country? Would she have permitted me to travel the way I did? What would have been her parting advice; and fears and hopes? What promises would she have had got from me? Whether she would have allowed me to go at all?”

While the warmth of the global Sikh community made Shergill feel at home even as far away as Yuba City, California, racism also raised its head, particularly in the U.S. Some drivers refused him rides. Despite his turban and backpack stamped with his home country, he suffered through anti-Mexican-immigrant diatribes from highway patrols along the Mexican border.

When he reached Oregon, a gas station attendant informed him that a string of motels up the road “will all be full.” Shergill wondered how the gas station attendant knew so much about local hotel occupancy until he learned later that the entire state of Oregon (along with many U.S. communities, including Bellingham) had sundown laws requiring non-white visitors to leave at night. So on his last night before arriving in Seattle, Shergill ended up sleeping in a cold, damp shed next to the highway.

But there were pleasant moments, too. He was swept up by a carload of young military recruits who went out of their way to a truck stop in Texas to try to find him a ride with a trucker. He met a migrant farm couple who took him many miles, sparing him the Texas heat. He also met an oil company employee who gave him a ride and $5 for dinner—just has he had met an executive in Germany who gave him a ride and five marks for meals.

His longest ride was with a family who took him 881 miles to San Bernardino, California. They were moving with everything they owned in two cars, one driven by the parents and the other by their grown son.

“There was one catch; I had to share the front seat with a huge dog in a non-air-conditioned car with windows open and New Delhi temperatures outside,” he wrote. “But who cared.”

Their first stop was a small town near El Paso. The family went to a motel while Shergill asked the sheriff for a night’s stay, as was common for single men traveling on a very tight budget. The sheriff let him stay the night in the office and brought him a home-cooked breakfast the next morning.

The next night, in Casa Grande, Arizona, Shergill was at another police station, filling out a form before picking out which cell to sleep in. The officer noticed his middle name, Singh, and told Shergill there were many Singhs nearby, including the biggest cotton farmer in the area. That night, the Singhs invited Shergill to dinner at the local country club and to sleep in their guest house.

Shergill made it to Seattle in September 1960 after traveling about 16,400 miles and spending $18, the equivalent of about $180 today.

The Journey Continues

The head of the UW foreign students’ office housed and fed him and encouraged him to drop the geography Ph.D. program in favor of broadcast communications. The best program was at Western State college, now Western Washington University. So, Shergill came to Western, excited about this burgeoning field.

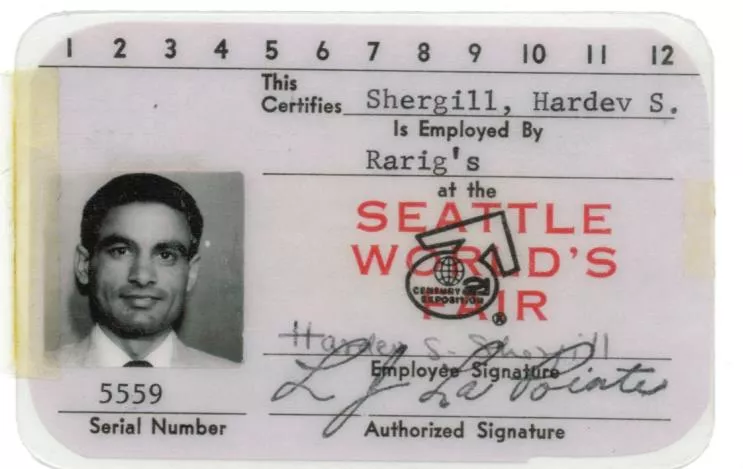

After a successful graduate career at Western, Shergill planned to work with a motion picture company at the 1962 World’s Fair. But his professor told him he wouldn’t sign the letter allowing Shergill to pursue labor as an immigrant, and that he should go back to India now that his studies were over.

Not one to be easily rebuffed, Shergill went to the dean of men, C.W. “Bill” McDonald, who signed the letter and wished him well. Shergill got the job and worked out of an equipment room at the base of the Space Needle, documenting the World’s Fair. But the bitterness of that professor’s refusal stuck with him, and he thought about it years later when he learned about Bellingham’s history of Ku Klux Klan activity and the 1907 riot to expel Sikh lumber mill workers.

In 1962, Shergill applied to immigrate to Canada, which had recently opened its borders to non-white people with skills in demand. Shergill was turned down flat, but he called the Immigration Minister’s Office in Ottawa, which sent him the paperwork he needed. He spent the next several years working in education all over Canada, both as a teacher and as an administrator.

Despite trouble breaking into the predominately white, tight-knit power structure of school administration, Shergill was a leader involved in establishing North Island College on Vancouver Island, advocating for the new campus while serving on a task force selecting locations for new community colleges. He also completed the feasibility study and served as the college’s first administrator. But after a well-connected British immigrant was hired as the college’s permanent leader instead of Shergill, who felt he was better qualified, he quit education and left Canada.

Shergill and his wife, Narinder, and their children settled in California where he had a successful real estate business. He publishes the Sikh Bulletin, which he started in 1999 to advocate reform of Sikhism, and served as editor for many years before retiring.

When Shergill learned that Sabah Randhawa—who grew up in Pakistan in the same region as Shergill’s hometown—was president of Western, he decided he would financially support Western and other universities that had touched him, his siblings and their children. He established endowments not only at WWU but at Sacramento State University, University of Calgary, and B.C.’s Douglas College and North Island College. At Western, the fund will support a student who is a single parent, at the request of Narinder, formerly a single mother.

Today, Shergill lives in California with Narinder and close to their three children, who visit and spend time with him regularly. Now 89, he still travels and stays active in the Sikh community, but his days hitching rides with families, soldiers, cotton farmers and humongous dogs are well behind him.