Open your eyes to all that is around you. What you are going to see in the next few weeks could change how you view the world.

It was one of the first pieces of advice from Carolina “Caro” Barona, the implacable Ecuadorian guide who would shepherd the WWU Honors College’s Ecuador summer abroad program through countless sights, sounds, and experiences this past July. It was also one of her most prophetic.

“I can’t think of any two weeks that have made a bigger impact on my life than these last two,” said Honors student Ayla Bilyeu, a psych and pre-med major from Monroe, at the group’s last dinner more than two weeks later.

So what happened between that first bit of advice by Caro and the joy-and-tear-filled last gathering?

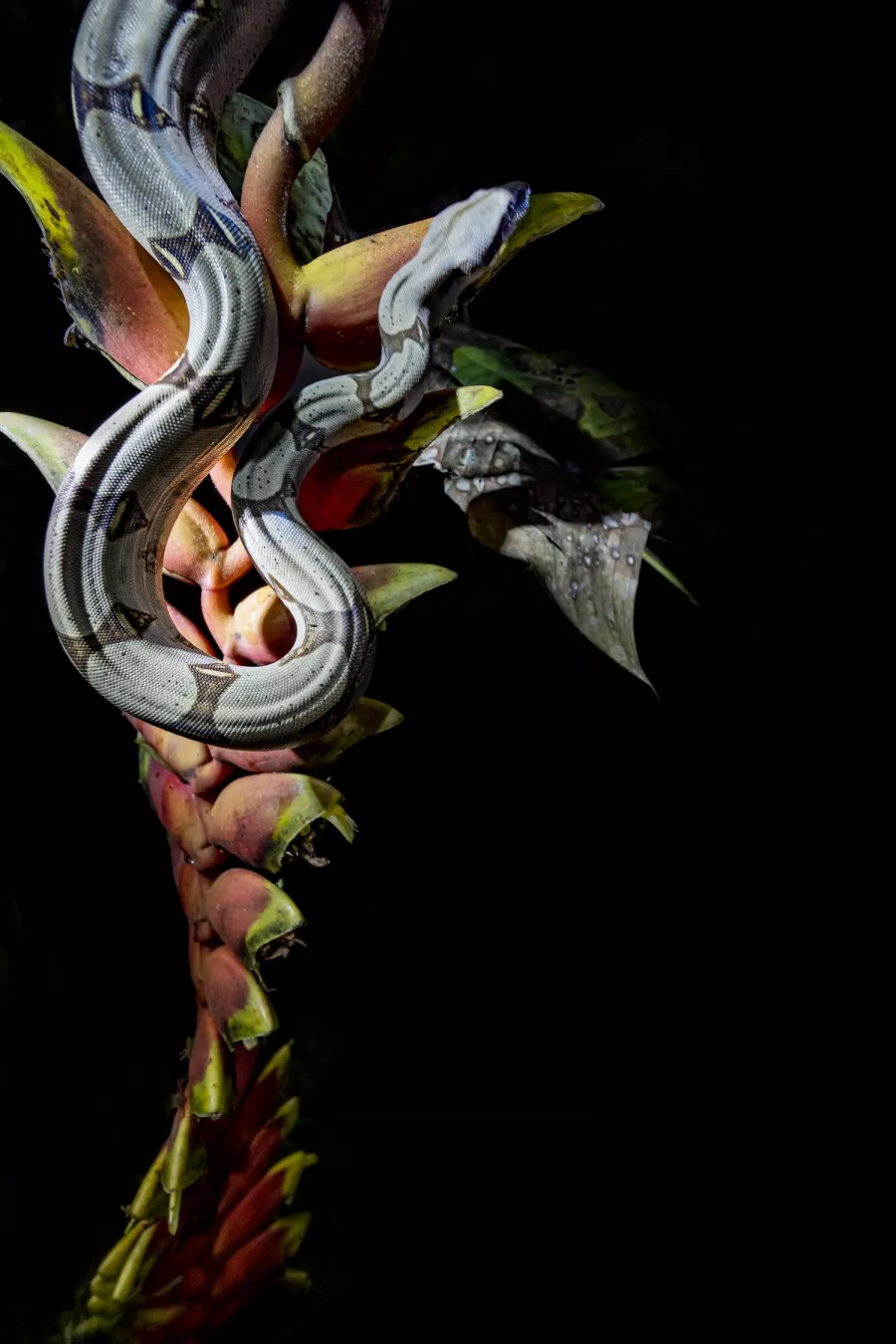

Snakes. Alejandro Murillo, the world’s most amazing bus driver. Andesite (lots and lots of andesite). Parrots. Soccer matches in the jungle. Piranhas. Spider Monkeys. Four-hundred-year-old churches. Chimborazo. Tarantulas the size of dinner plates. The studio and imagery of painter Oswaldo Guayasamín and the words of Ecuadorian author Maria Virginia Farinango. The gentle, forgiving gaze of a 150-year-old tortoise the size of a refrigerator. The Night Bus. Watching the sun set over the Rio Napo. The phrase, “Is your buddy here?” Grubs for lunch (imagine a wriggling Vienna sausage). And, most importantly, a group of 21 Honors students who, thanks to COVID, barely knew each other at the start of the trip – and who by the end had bonded into an unbreakable circle of friends.

But let’s start at the beginning.

The Honors Ecuador program is distinctive in its interdisciplinary structure: the Faculty-led Global Learning Program is led by two faculty members who teach two very different topics. Senior Instructor Amy Carbajal from Modern & Classical Languages teaches the language/humanities/cultural immersion half of the course, while Honors College Director and Geology Professor Scott Linneman teaches the geology half. So the scientists in the group get a heavy dose of the humanities, and vice versa.

It's challenging for faculty from separate academic disciplines to lead a joint Global Learning Program. "It’s hard to do,” Carbajal says. “You have to have two faculty members who are really, really on the same page about outcomes and content … and they have to be willing to compromise and work together to get that content delivered.”

“We know it’s a different approach, but that’s one of the things that makes this program really special,” says Linneman, who has taught the Honors in Ecuador program three times – including twice with Carbajal.

Linneman and Carbajal were joined by Biology Professor Deb Donovan (along with her husband, Political Science Professor Todd Donovan, who tagged along on his own dime), who would dig into the marine science component of the trip once they got to the Galápagos.

Quito Video Description

Video opens at night, on the sculpture "For Handel" outside the Performing Arts Center at Western. Pan to a Bellair shuttle pulling up at the curb. Professor Scott Linneman walks up to the shuttle as students gather in a circle behind him. Students begin boarding the shuttle.

The shuttle has arrived at the airport, and bags are being moved to the curb.

Aboard an airplane passengers are finding their seats.

Students are rolling luggage through an airport in Quito. The students, all wearing N95 masks, gather at this airport, as two women gather into an emotional embrace. Outside the airport, Western students and other travellers gather at the curb awaiting transportation.

Aboard a bus at night time, a Western student dances happily down the aisle as he finds his seat. The camera pans to the door, where more students are boarding the bus. Looking out the bus window, a decorative sign reading "Quito" sits outside the airport, and then fades into streetlights zooming by. The camera then fades to students exiting the bus at their destination.

A large hill lies in silhouette as the sun rises behind it. Fade to a misty view of a city, and then to gondolas arriving at a station. Students take their seats on a gondola, and then the camera moves to look out the window as it leaves the station. The weather is rainy outside. The camera pans over a National Geological Map of Ecuador that a student has opened in front of them.

Scott Linneman is talking to a group of gathered students inside a tourist center. Everyone is wearing N95 masks and rain jackets.

Clouds travel over a grassy hill. Two students swing together on a hill overlooking a city, as though they are about to take flight over it.

Cutaway to a photo montage:

A black and white shot of electric towers on a rocky hillside.

Thick fog over a grassy knoll, with a fence.

A student in a red jacket swinging over the city.

Knobby hills overlooking the city, with students standing on one hill in the distance.

A student standing between and embracing two llamas.

A student smiling enthusiastically against a cloudy backdrop.

Cut back to video, a student blows into a small ocarina tied around their neck and laughs as Sean asks them if they got a little souvenir.

After a vigorous Prep Week – which included assignments on Ecuador’s culture and history, lengthy discussions of the two books of required reading for the program, as well as deep dives into the active geologic history of Ecuador - the group met in front of the Performing Arts Plaza on campus at 2:30 a.m. on Sunday, July 3, to board a bus to SeaTac and fly to Atlanta. There, they caught a 5 1/2-hour flight to Quito, the capital of Ecuador and a city of nearly 3 million inhabitants.

“I’m not sure what I expected, but this city is huge,” said student Noah Goodwin-Rice, a biochemistry major from Newport, Oregon, gazing down at the city from atop the nearby peak of Pichincha. Quito sits in a valley atop the Andean highlands at more than 9,000 feet above sea level; a long, thin city, it stretches for miles across the low saddles between Pichincha and the foothills of neighboring volcanoes such as Antisana and Cotopaxi.

Claire Hutchings, an environmental science student from Bothell who will be a senior this fall, said she was just happy to be in Ecuador, as the two weeks leading up to the departure saw her get a case of COVID and see the trip almost canceled because of strikes and protests led by Indigenous leaders against rising gas and food prices.

On top of that, the global spike in fuel prices related largely to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused a price jump of over $1,500 per person that would have been untenable for many of the students. But a single call to the Western Foundation by Linneman and Carbajal solved that issue, as WWU Vice President of University Advancement Kim O’Neill agreed to pick up the overage so students’ cost would remain the same.

All hurdles had been cleared at the 11th hour, and just days later, Quito lay before the students like an open book.

“I am just so happy we made it,” Hutchings said.

There was little evidence of the unrest that had almost nixed the trip; life had returned to normal in the capital.

A walking tour of the historic city center, a UNESCO World Heritage site, illustrated the importance of the Catholic Church in Ecuadorian society and inspired the first of many conversations about syncretism: the amalgamation and assimilation of different religions and cultures over time.

For example, the Catholic Church built many of Quito’s cathedrals and churches atop Incan holy sites (Quito was the capital of the northern half of the Incan Empire) in an effort to assimilate the pre-Catholic faiths of the region.

The group saw the same pattern elsewhere, among other cultural groups; when the group toured the ruins of Cochasquí north of Quito, they learned that the 15 truncated pyramids on the site were built around 950 CE by the Caranqui people, who used it as a center for religion and trade for hundreds of years before it was finally conquered by the Inca, who then brought their own belief structure to the region.

The Incans’ victory would be short-lived as their conquest of the Caranqui was followed by an Incan civil war and the arrival of the Spanish. The dissolution of the Incan Empire and the arrival of the Spanish set in motion the cultural and societal underpinnings of what would emerge as modern Ecuador in the 1800s.

Wren Hart, a psychology major who graduated after finishing the Ecuador course, said Cochasquí’s history and culture were eye-opening.

“The incredible effort over hundreds and hundreds of years to build this site is something you almost have a hard time wrapping your head around,” Hart said. “And thankfully the Spanish never saw it as valuable because it probably wouldn’t be in the condition it is in today if they had.”

Goodwin-Rice said the weight of thousands of years of settlement at Cochasquí was palpable at the site.

“This one spot has collected so much history -- thousands of years’ worth -- and you can really feel it,” he said.

Otavalo Video Description

Inside a solar clock looking up, the camera pans down to Professor Linneman lecturing to students. The solar clock is an orange cylinder structure, approximately 3 stories high and 10-15 feet diameter at the base.

Inside a greenhouse, plants grow in rows. A woman lays fronds of a plant onto a scale.

The Western group hiking along a green flat, with Amy Carbajal talking to John Thompson in front. Students look out into a grassy field as the wind blows softly through their hair. A small, scruffy dog does the same.

Inside a bright building with arched windows, one student braids another's hair while Amy Carbajal passes out notebooks.

Students walk around a museum, looking up to take in the brightly colored stained glass windows around them.

On a grassy hill, Linneman watches students walk past.

Carbajal giving a lecture in a town square.

Students walking down a narrow catacomb hallway.

Students gathered on the top of a Catedral Metropolitana de Quito, next to its checkered yellow and brown dome roof.

A student and professor walking up a hill on a brick sidewalk.

Students cheering with matching lime-green beverages in mason jars.

Students running in a circle wearing a hat with ribbons hanging down.

A person dancing in front of a church. The camera pans up on the church's intricate gothic architecture features.

Cut to photo montage:

Students lined up in front of the solar clock.

The checkered and domed roof of Catedral Metropolitana de Quito

Students crossing the street in front of a mural of a flute player.

A large, snowy mountain peek surrounded by trees.

Two rows of green houses

Two students standing next to green houses.

A dramatic black and white shot of clouds over the hills next to Otavalo.

Sun peeking through a cloud onto green hills.

A group photo of the students and professors next to a lake.

Two windblown llamas on a hill.

Cut to a time-lapse of the city at night, clouds roll overhead as city lights twinkle.

Amazon Video Description

We’re seeing the green mountains passing by from a bus window, then look out the front windsheild as the bus navigates over a stream flowing over the road. A few brick buildings and mist-covered mountains, then we see the students walk down a river embankment to four covered canoes. The Ecuadorian flag on our canoe flutters in the breeze as we motor down the wide river. We hang over the side of the canoe and see the water splashing in the wake, and see students in another canoe speeding along in the fading light. The channel narrows and a guide uses a pole to push us along; a student trails their fingertips in the dark green water.

Guides pull the boats ashore a muddy beach and the group gets out of the canoes. One student crosses a hanging rope bridge. A guide speaks to the group while demonstrating something with a large knife and a stick. Students walk and talk to each other among the lush Amazon vegetation.

At nighttime, we’re on a platform bridge, the only light apparently coming from our headlamp. We see a brown, hairy tarantula on a green pillar, surrounded by students taking its picture.

A photo montage: A black beetle with what looks like a curved rhinoceros horn. A double waterfall. Lush, green treetops seen from above, surrounded by mist. A student carries a large backpack out of a river canoe. Amy Carbajal and Scott Linneman smile on the riverbank. Students, some carrying luggage, gather on the shore of the river. The moon rises over the Amazon. The red-roof cabins of Yacuma Eco Lodge, nestled in a tree-covered hillside, are lit up at night.

After exploring Quito and heading north to Cochasquí, the volcanic caldera of Cotacachi, and the market town of Otavalo, it was time for the long descent from Papallacta Pass down the east slopes of the Andes to the Amazon basin, replacing the high, thin air of Quito with the heat and humidity of the jungle at the Yacuma Ecolodge.

At Yacuma, the students took a guided jungle walk and learned about the names and uses for many flora and fauna, like trees known as “walking palms” which slowly move with the growth of new roots. They also spotted a few of the hundreds of bird species common to the Amazon, and learned which shrub hosts the tasty lemon ant, known by the Kichwa, Ecuador’s largest Indigenous group, as a quick source of protein when foraging in the jungle.

Other activities at the lodge included a nighttime “critter walk” that revealed everything from a boa constrictor to huge, furry tarantulas; gold panning on the Rio Napo; an afternoon bird walk with parrots, macaws and squirrel monkeys; fishing for piranha in one river and tubing in another.

Audio file

Audio Description

Various tropical birds and insects chirping over one another, fading in and out of each other continuously. Occasionally a bird calls out in a louder and more melodious way, or the buzzing of insect wings can be heard.

Perhaps the most memorable activity was a short hike to a local Kichwa community, where the students were introduced to a family who shared with the group what life was like in Kichwa villages across the Amazon basin.

Farmers of such staples as yuca, corn, papaya, plantain, and cacao, the family opened their doors to the group and led demonstrations on cooking local food and preparing chicha – a local fermented drink that varies from community to community. They also introduced students to the Kichwa art of hunting with a blow gun.

A spirited pick-up soccer game among the students, local children, and the guides was the highlight of the day, as gales of genuine laughter echoed through the dense jungle, and the shared joy brought the students closer to the community and its people.

“The language barrier just totally broke down,” said Samantha Herlich, an environmental studies major from Pleasanton, California. “We just laughed and communicated together so easily.”

The group’s local guides, Fausto Imuez and Rolando Benjamin Cerda Licuy, proved to be crucial in not only connecting the class to the incredible biodiversity of the region, but, more importantly, to its inhabitants.

“Without our guides, we wouldn’t have known anything about this amazing place. They didn’t just give us a series of lessons, they immersed us in their culture firsthand, which was so much more impactful,” said Jessica Dietzman, a business and sustainability major from Sequim.

Environmental science student Amelia Bourne of Northampton, Massachusetts, agreed.

“The relationship between our guides and the natural world around them - and how closely they are tied to that environment as a way of life - is just amazing,” Bourne said.

As she took one last canoe ride along the Rio Napo, biology major Jordi Baron of Bellingham reflected on her time in the Amazon.

“These people and this place … I don’t see how I could ever forget them, or forget what it felt like to be here,” she said.

Baron later wrote more about her Amazon experiences in her journal.

“I have no words. No way to profess the awe I feel, and the humbling sense of how small I really am,” she wrote.

Cuenca Video Description

Mist floats over green mountainsides. A student in a hooded raincoat walks on a cliffside trail next to a waterfall. A group of students stand in an alcove behind the rushing waterfall.

A smiling student swings out past us on a swing at the cliff’s edge, feet pointing into the cloud-covered heights. Misty fog creeps over the grassy hillside of Ingapirca, which is crisscrossed by old stone fences and pathways. Students walk up a pathway among stone ruins. More fog flows up the mountainside like water over a rock.

Back in town, students stand in a sunny town square, listening to a guide. We see one student listening and nodding. They’re inside a building surrounding a display of volcanic rocks hanging by rope from a rod, like wind chimes. A guide taps each rock and we hear musical “plinks” in different tones.

Students are outside on a fog-covered hillside, listening to a faculty member. The Ecuadorian flag flies against a bright blue sky.

Cut to a photo montage: students smiling among the misty drops of the waterfall, one attempting to catch the drops in their hands. The group crosses a hanging rope bridge over a gorge, a student swings from a tree swing, an elaborate tree house in the background.

A hummingbird with vibrant green feathers on its head sits on a branch. Students walk in a line along a roadside stone wall, over a cobblestone sidewalk, green hillsides in the background. A wooden platform with the sign “Ingapirca” overlooks a grassy hillside doted with houses, trees and barns. Twin spires of a cathedral dominate the skyline of Banos, surrounded by mountains. Ingapirca’s stone ruins on a green hillside. An alpaca stands on a grassy hillside before the stone ruins. Students walk through a narrow street in town.

Mountainsides in the Andes. Students follow a trail along the hillside. The group walks up a trail away from a lake, mountain-peaked skyline in the background. Portraits of a student sitting on a mountainside, weaving a friendship bracelet on a water bottle with a mountain peak in the background, and another student examining a rock.

After a sad farewell to their new friends at Yacuma, the students and faculty began sections of the trip that brought them back up and across the Andes, with stops in Baños (a group favorite for its laid-back, friendly vibe), Riobamba, and the gorgeous southern highlands city of Cuenca.

But the high point (pun intended) of this section of the program was the day spent on the slopes of Chimborazo volcano, Ecuador’s highest point at more than 20,000 feet – almost twice as high as Mount Baker.

As Murillo inched the Night Bus (named by the students in honor of the physics-busting mass transit vehicle from Harry Potter) up the slopes, three students - Annabelle Carozza, Braden Brask, and Noah Goodwin-Rice - gave a presentation on the impact of the active volcano on its surrounding area. The trio pointed out lahars, ash flows and sediments, and kept an eye out for the moraines left by retreating glaciers.

Carozza discussed in great detail the types of rocks littering the landscape.

“These scoria were formed when basaltic magma was erupted from the volcano,” she told the group. “Most people just call them ‘lava rocks,’ but the correct name is ‘scoria.’”

The group climbed through the lunar landscape of Chimborazo through a stiff breeze and dense clouds with temperatures in the low 40s (a far cry from the damp heat of the Amazon just a few days before) to the first of a pair of refugios (shelters), where many turned around; others pushed on to the second refugio, at exactly 5,000 meters or 16,404 feet above sea level, higher than any mountain peak in the U.S. outside of Alaska.

After a fortuitous parting of the clouds revealed Chimborazo in all its glory, the exhausted group tumbled back into the Night Bus.

Galápagos Video Description

A speedboat bounces over the waves with students in the back. Cut to students walking along the water’s edge of dark brown lava rock, tall cacti in the background.

Back to the boat, students don fins, masks and other snorkel gear. We follow one student who jumps into the water, and we see them underwater, looking at the camera.

A student in a wetsuit laughs in the back of a speedboat, wind flowing through their hair.

Cut to a turtle swimming under water, then two turtles swimming among small, colorful fish. Then we see students swimming in the background, watching the turtles. A school of small silver fish swim past a snorkeling student.

Back on land, students are in an animal sanctuary gathered around an iguana with spines on its neck and back. Then we see them surrounding a giant tortoise.

Next they’re following Scott Linneman into a dark lava tube. Linneman is carrying a light and lecturing as he walks, the students trailing behind him.

More tortoises.

Sea lions gather on a waterside deck, watching the students as they listen to a guide.

More students observing tortoises.

Students stand at the edge of a volcanic crater filled with black rock against the green hillsides and blue sky. We follow them as they trek up the hillside.

Back to the students snorkeling, we’re at water level with a student smiling broadly, snorkel mask on their face. Underwater, students wave at the camera and we see sea lions darting around. We follow a student rising to the surface, head popping above the water next to lava rock ledges. More sea lions swimming playfully.

Cut to a photo montage: a giant tortoise, students sitting on the grass between two tortoises, a student looking over their shoulder as they walk down the lava tube, a red crab clinging to a black lava rock while a wave crashes around it, a tortoise resting on a rocky beach, a close-up view of the scaled texture of a tortoise’s head, the black sand and rocks of the volcanic caldera, and a group shot of students and faculty in front of the crater.

More photos: Penguins, waves crashing on rocks, blue-footed boobys, a turtle underwater, lit from above, with three snorkeling students floating and watching in the background. Snorkeling students seen underwater and from below, seen in silhouette against the bright surface. A turtle swimming along the bottom of the cove, kicking up debris and tiny black fish with yellow stripes. A student treading water with a school of gold-colored fish swimming past their swim-finned feet. A spot of green plant life in the middle of the black rock crater. The group listens to a guide at the edge of the crater.

The final – and perhaps the most anticipated – leg of the trip lay ahead: four days in the Galápagos Islands. Like the Amazon, the Galápagos are one of the most biodiverse locations on the planet. It was on the Galápagos that scientist Charles Darwin, during his second voyage on HMS Beagle, made the observations and collections that helped frame his groundbreaking theory of evolution by natural selection. With a huge number of endemic species, including the famous group of birds known as Darwin's finches, it was a perfect place for him to work on his hypothesis.

“Darwin’s finches are in every bio textbook I have ever had,” said biology major Delphine Maurer. “Being here in his footsteps is just incredible.”

The wide-eyed students soaked up everything about the islands of Santa Cruz and Isabela, from touring a tortoise sanctuary to tiptoeing over groups of snoozing marine iguanas, swimming in the emerald swells of the beach on Isabela, and snorkeling among sea lions, “sleeping” white-tip sharks and giant green sea turtles.

A 10-mile hike up the slopes of Isabela’s Sierra Negro, which last had a major eruption in 2018, revealed its impressive caldera – a massive cone about 7 miles across. The guides described the odds of a calm day with blue skies atop Sierra Negro in the rainy season to be about a 1 in 20.

“I’m pretty sure this is the widest basaltic caldera in the world, so you are really seeing something special,” said Linneman. “And look at this day - are we lucky or what?”

The pending end of the program was on the minds of a couple of the students on the walk back down and that night at dinner.

“In some ways it seems like we just started the trip – but when I think back to the things we did in Quito or in Otavalo, it also seems like that was months ago," said Anna Byquist, a biochemistry major from Spokane Valley. “And we have seen and done so much.”

Fellow student Collette Webb agreed.

“It’s just hard to believe it’s almost over,” said the environmental science major from Fort Collins, Colorado.

The final night's group dinner in Quito was an opportunity to share and reflect, with both faculty and students rising from the long table to make toasts and look back on not only all the things they had seen, but even more importantly, about the relationships forged through 19 days of demanding travel and full immersion into a new culture.

Stories were shared and glasses of lemonade raised to memories and new friendships.

"Because of the pandemic, I feel like I was sort of robbed of an opportunity to really get to know my Honors cohort," said Bilyeu as she held up her cup in a toast. "But now, after this, I feel like there isn't a single one of you who I haven't shared a profound moment with on this trip, and for that I am so thankful."

The two most common words at the group's last dinner together seemed to be "remember when," followed by gales of laughter and a few tears of joy and gratitude for all they had seen.

But more treasured than any single event seemed to be fond memories of shared comradeship that, the more they talked to each other, seemed to be one of the most important goals of the trip for all of them – new, deep, and meaningful connections with their peers.

"I can't say enough how incredible I think you all are, and how thankful I feel to have been able to share these two-and-a-half weeks with all of you," said Dietzman as she toasted her fellow students.

Linneman echoed those thoughts with his own toast to the group.

"We've never had a student group in this program as big as this one, but when we were interviewing all of you, there wasn't a single one of you that we thought didn't deserve to come, and who wouldn’t grow because of what we would see and do together," he said. "And we were right. You all are amazing humans."

A tearful Carbajal thanked the group for their insight, their desire to immerse wholly in the cultures of an amazing but completely foreign country, and for their unbending quest to learn. Looking out at the table lined with faces who she said had made such an impact on her, she raised her glass to the group, and her toast was as simple as it was heartfelt.

"Thank you," she said.

Story Creators

John Thompson is the assistant director of the Office of University Communications. Seeing the peaks, jungles, islands and incredible people of Ecuador - and getting to know 21 amazing students - was one of the highlights of his career.

Sean Curtis Patrick is Western’s director of visual media productions. An artist and musician, he previously worked at University of Michigan, where his documentary about student research in Greenland won an Emmy Award.