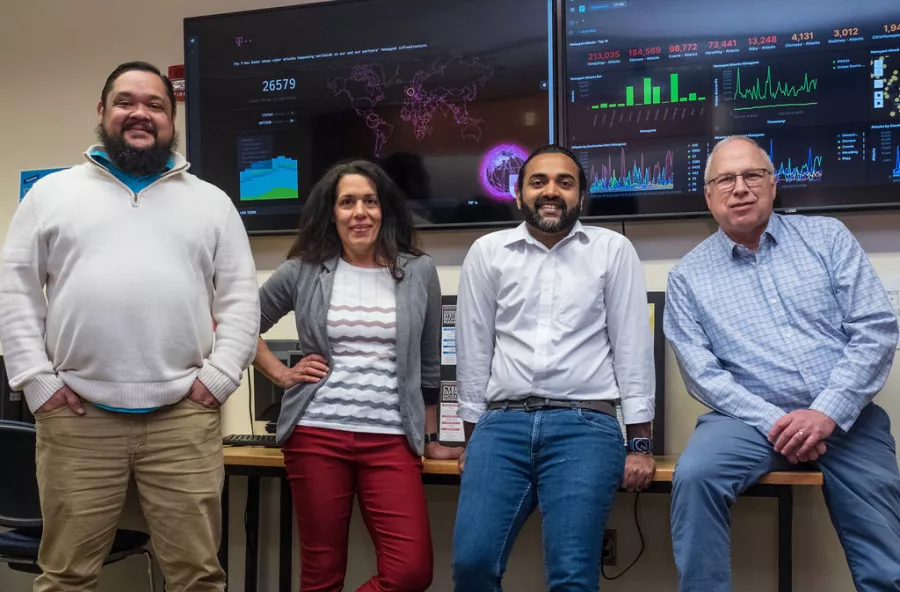

WWU seniors Robert Crocker and Shaine Metz spend a lot of time thinking about crime.

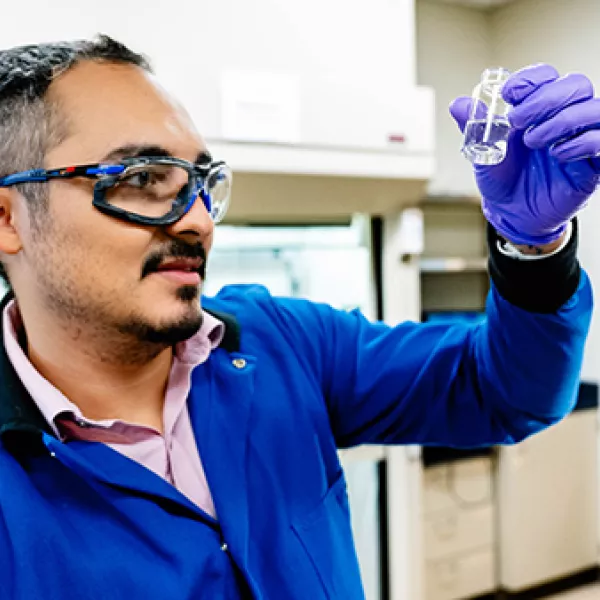

It’s a central focus of their degrees: Both majors in computer science and cybersecurity, Crocker and Metz are working with other students to develop “honeypots” that lure cyber criminals into sharing their dirty tricks and teaching students how to prevent future cyberattacks.

Like spies who use sexual and romantic subterfuge to manipulate their victims, honey pots present themselves as ripe data targets for hackers. As the bad guys try to break in, programmers are watching their progress and taking note of how to prevent real attacks on more vulnerable assets.

Honeypots are a big part of the research work Crocker and Metz are doing in Western’s Cybersecurity Program, based at the WWU Center at Olympic College Poulsbo. They’re focusing on protecting military-grade devices that are connected to the internet; the Internet-of-Things is coming under increasingly frequent and sophisticated cyberattacks.

“Different sectors are being targeted by attacks all the time,” says Crocker, of Lynnwood, “and from the perspective of a security analyst, you’d see behaviors in traffic that would indicate some sort of malicious action is happening. But it’s happening in real time and real systems are at stake.”