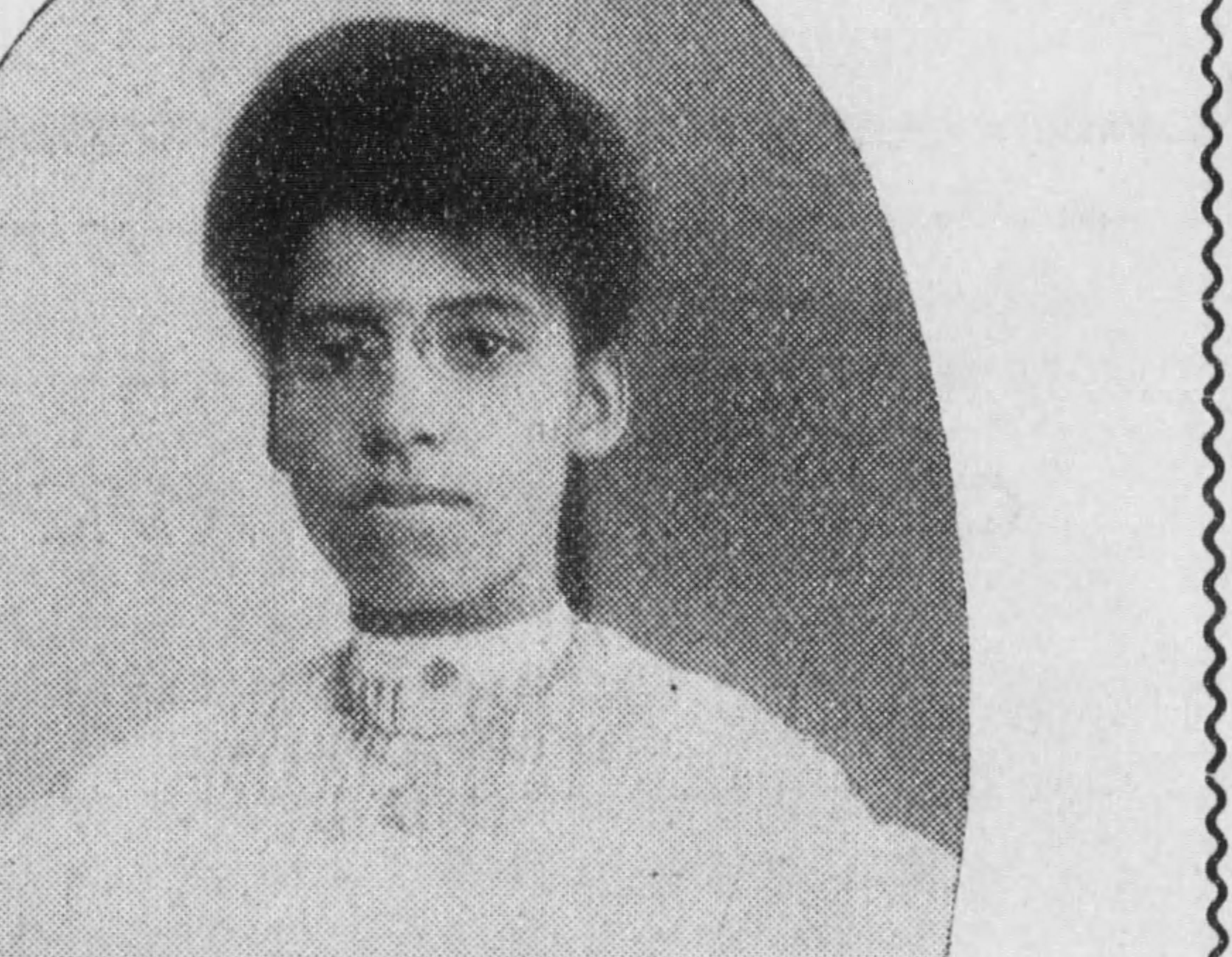

When Alma Jordan Clark rode the train up to Bellingham in January 1906 to become the first Black student at the State Normal School, she had her cousin at her side and her community at her back.

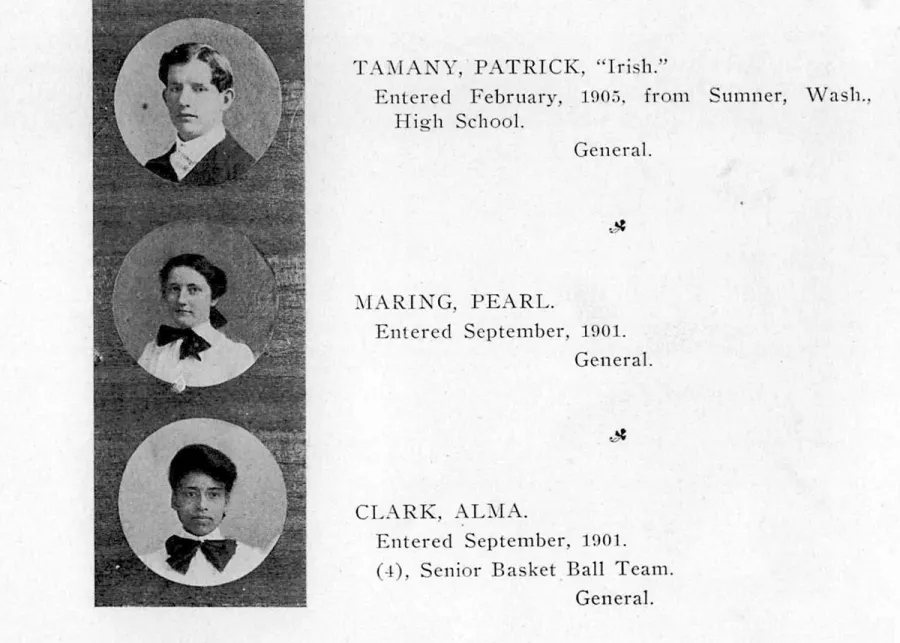

The daughter of one of the most successful Black business owners in Seattle, Clark was the third Black student to ever graduate from the city’s high school at a time when attending high school was rare. The Clark family was often mentioned in the Black-owned Seattle Republican newspaper, which called her graduation party the previous summer “the grandest affair of the season,” complete with speeches and musical performances by classmates, elaborate decorations of flowers, ferns and ribbons, and place settings for 30.

But her reception in Bellingham, a community with a legacy of driving out people of color, was not nearly as grand.

The Bellingham Herald took a sensationalized view of Clark’s arrival, reporting that her appearance caused a “commotion” on campus: “For a time there was talk of a general exodus from the school should the faculty persist in its determination that she shall remain,” the town’s paper reported, “and indignation meetings were held in various rooms.” The story goes on to include comments from classmates who vouch that Clark was “highly intelligent” and “most ladylike.” “It would be a shame to drive her out of school,” one student told the paper.

The Herald reported that she remained in her room that first night in Bellingham instead of joining the other boarders for supper, but in the morning, she appeared at breakfast and “sat at a table with several young ladies who were democratic enough to receive her on equal terms.”

“Miss Clark announces that she intends to stay, and that she is deeply grateful to the faculty for coming to her defense, and to Miss Blanchard, who accepted her as a boarder without a second’s hesitancy,” the Herald reported. “The students are still divided on the question as to how she shall be received. Some of the more outspoken students insist that she be ostracized while others are inclined to take a broader-minded view of the whole affair, and receive her on equal terms. The leaders of the latter faction quote from speeches of President Roosevelt on the subject, and declare that if the president of the United States is not too good to eat at the same table with [Booker T. Washington,] a highly respected colored teacher, then they should not consider themselves above doing the same thing with a girl student, who is having a much harder time than any of the rest of them to secure an education on account of the color handicap, and they are determined that her color shall not be a handicap to her, while she is a student at the Washington State Normal School.”

Bellingham Normal School Trustees meeting minutes reveal their frustration with the Herald’s portrayal of Clark’s arrival and “race prejudice” on campus:

“Dr. Mathes stated that, so far as he knew, no such feeling existed, and he explained the coming of Miss Clark, who with her brother, had talked over the possibility of any race prejudice as an outgrowth of her presence at the school. At the conclusion of the discussion, Mr. Donovan introduced the following resolution, which was unanimously adopted with the understanding that it be published in the Herald, which had given publicity to the story that a feeling of bitterness had developed at the normal. The resolution was:

“Whereas, - Certain misleading statements have been published regarding the race question at the Bellingham Normal School,

“Resolved that the school is for the benefit of all the people of the State of Washington, regardless of color, race or politics, good work and good morals being the essentials required of students.”

Clark’s enrollment at the Bellingham Normal School was also covered by the Seattle Republican, the city’s first successful African American newspaper, founded by Horace R. Cayton Sr., a former slave, and his wife Susie Revels Cayton, associate editor. According to the African American Registry, “the paper sought to portray ‘the black race’ in a positive manner and hoped to create harmony between races through open discussion of sensitive race issues.”

While railing against “those young white ladies” who would have refused Clark’s place at Bellingham Normal, the Caytons praised the trustees for affirming her right to be educated in Bellingham: “If the heads of all public institutions would but take the same firm stand, on the mooted race question of this country as did Principal Edward T. Mathes, who unhesitatingly made the young colored lady feel that her rights would be fully protected in his hands, there would be less such interracial upheavals. While Prof. Mathes but did his plain duty, nevertheless he did it so completely that every Negro in this country, as well as every Caucasian who wants to see all manner of man have a square deal, should feel everlastingly grateful.”

A founder of Seattle’s NAACP

Alma Jordan Clark was born in 1884 in Tennessee to Anna Rogan and Robert A. Clark. Although both parents were born before emancipation, Alma’s mother was a school teacher in Mississippi prior to her marriage, indicating she also had received education.

The oldest of six children, Alma was 5 when her family relocated to Seattle in 1889. Robert A. Clark started the city’s first parcel delivery service, known as the largest and most successful Black-owned business in Seattle, in 1904. He was also a charter member of Mount Zion Baptist Church, which remains Washington’s largest African American church congregation.

Totaling a few hundred at the time, Seattle’s Black community experienced an unusual level of acceptance and opportunity. Among Seattle’s middle-class so-called “race families” of the period, the Clarks’ relative prosperity gave Alma the opportunity to further her education at a time when it was uncommon for most people to attend high school.

After she settled in to Miss Blanchard’s boarding house, we know very little about the remainder of Clark’s experience at Bellingham Normal. She took courses in psychology, geography, physical culture, biology, and botany, as well as observation and practice teaching. After completing her first year, Clark was appointed to an assistant librarian position in Seattle, receiving the highest scores on civil service exams. It appears she did not return to the school.

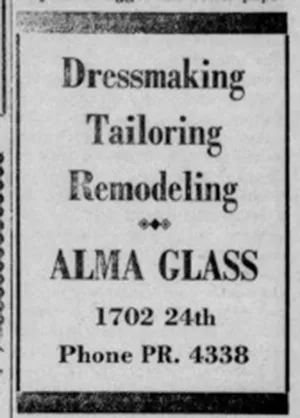

In 1909 Alma married Stephen A. Glass, a clerk in the Seattle Post Office. Their son Stephen Jr. was born in 1910. Taking on the role of wife and mother, Alma spent her son’s early years at home and later worked as a seamstress.

As the Black population grew in the Pacific Northwest, discrimination increased and opportunities for advancement became harder to find. In October 1913, Alma Glass was a founding member of the Seattle branch of the NAACP, one of the first branches west of the Mississippi. The Seattle NAACP staged protest marches, filed lawsuits against discrimination, and protested the 1915 Ku Klux Klan propaganda film, “The Birth of a Nation.”

Alma Glass was also a lifelong member of the Washington State Association of Colored Women, chairman of the Seattle Self-Improvement Club in 1939, and served on the board of directors for the Seattle Urban League during the 1940s.

The NAACP was Clark Glass’s “family outside of the house,” remembers her granddaughter, Juanita Glass Laney, who lived with her grandparents from around 1958 to around 1964. “I was extremely close with grandma,” Laney remembers. “My formative years, I was with her.”

Laney attended Madrona Elementary School and lived with her grandparents in Seattle from age 6 to 12, spending summers at home with her parents in Los Angeles.

Juanita was her grandmother’s near constant companion in those years, following her to the Seattle NAACP, where Juanita was tasked with running the ditto machine while her grandmother worked in the office. “She had her work, I had mine,” Laney remembers. “We had a community around us. Everyone was just really friendly to one another.”

They lived in the Glass’s house on 24th Avenue, walking distance to Mount Zion Baptist and Madrona Elementary. The Glasses rented out the bottom floor of their house and had additional rental properties in Seattle. “She was quite a buisnesswoman, I think,” Laney says.

Laney remembers yearly family trips, Alma always at the wheel, to Port Ludlow to cut down the family Christmas tree, and to Spokane to see Alma’s sister, Theodosia. Alma also took care of her husband Stephen, who by then used a wheelchair due to arthritis. But in 1964, Stephen Glass Sr. passed away and Stephen Jr. insisted his mother and daughter move to Los Angeles. Alma Clark Glass died in L.A. a year later in 1965 at age 79, and is buried with her husband in Sunset Hills Memorial Park in Bellevue.

“My grandmother was a strong, independent woman,” Laney remembers. She was an avid reader, but never forced her granddaughter to read. She made her own clothes, and tailored store-bought clothes to fit—Laney still has some of her grandmother’s dresses and church hats. And she kept her maiden name throughout her life.

But she never talked about her time in Bellingham.

So when Leonard Jones, WWU director of University Residences, called Laney and her husband David with news that the university was naming its newest residence hall after Alma Clark Glass, the couple thought it was some sort of scam. “Until he got to the NAACP,” Laney says, “and that made me take a breath and sit down.”

The Laneys and Juanita’s younger sister want to come to Bellingham to see the opening of the new home for students at Western later this fall.

Alma Clark Glass probably wouldn’t have a lot to say about the new residence hall that will carry all three of her names, her granddaughter says. “She would probably have a sheepish grin,” says Laney. “I know she’d be proud. She’d be very proud.”