The story we tell about our lives is a story of how we view ourselves—and how we want to be seen.

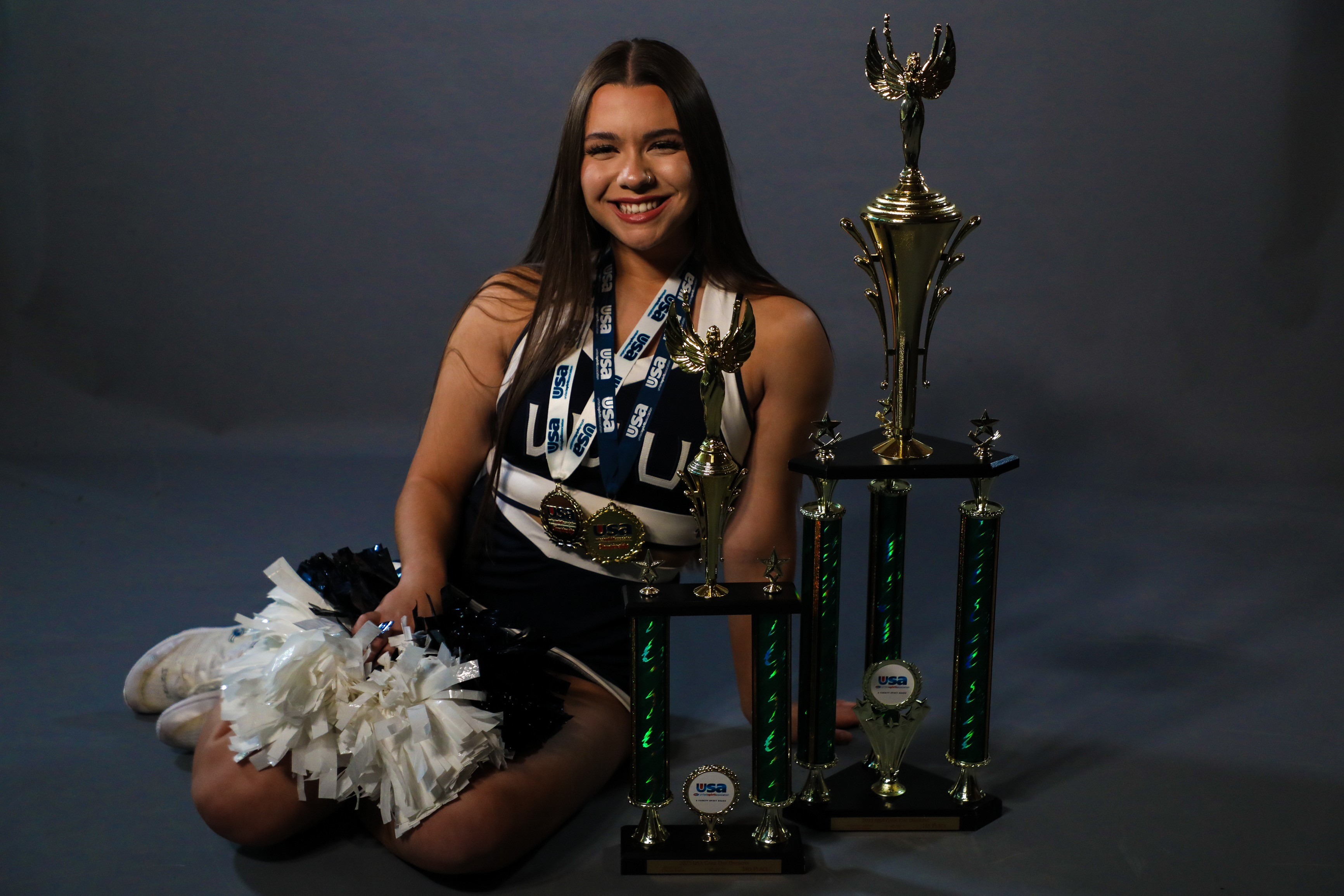

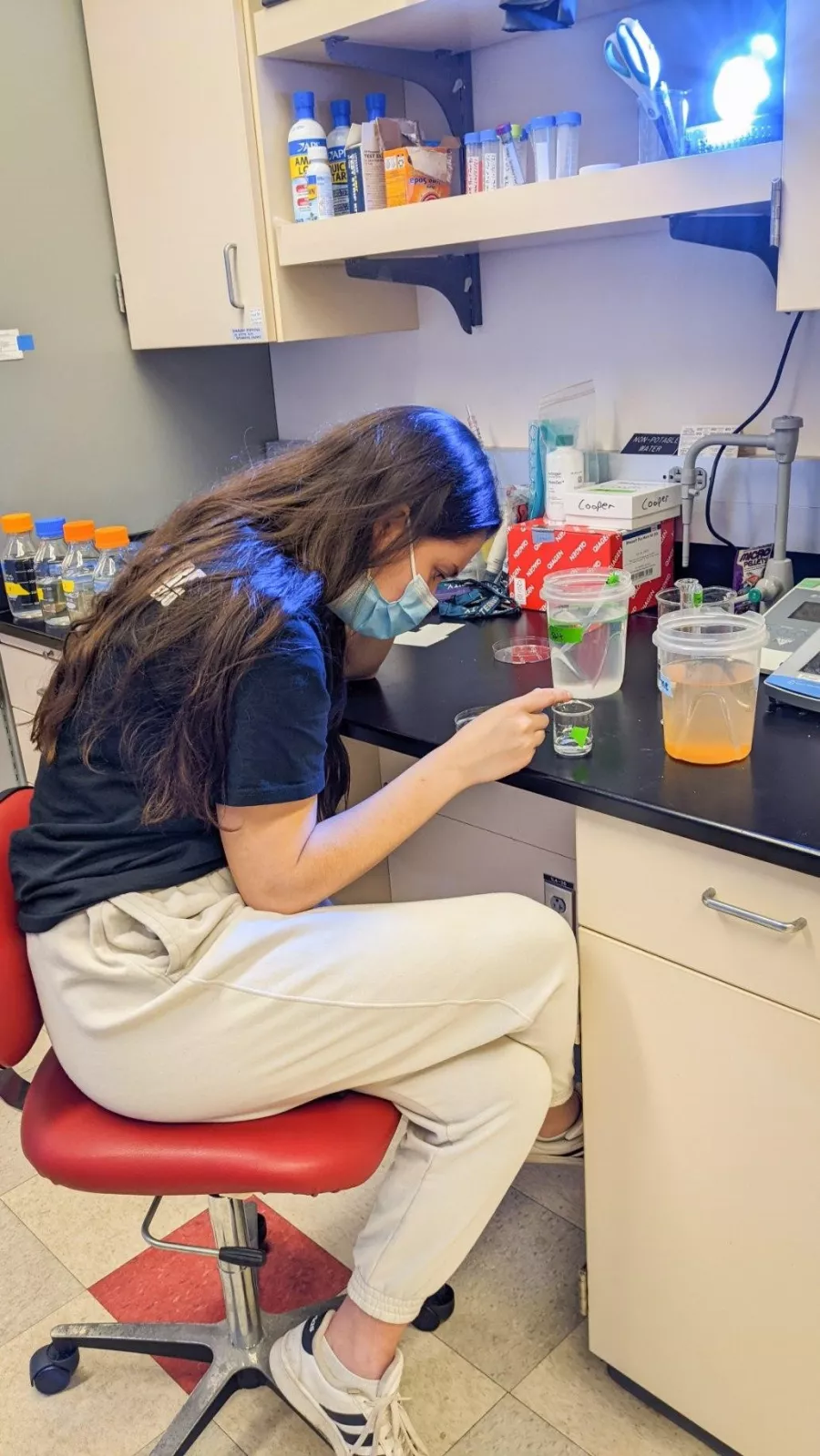

For Amirah Casey, the first Outstanding Graduate of Western’s Marine and Coastal Sciences program, her story was one of success: immersing herself in marine science research, becoming the first undergraduate at WWU to teach a 200-level Biology lab section, co-leading Western’s cheer squad to its first national championship, and receiving full funding to attend a renowned graduate program at the University of Washington.

Her story is also about a young person whose parent experienced homelessness and addiction, and who lived with the stigmas that come with both. This is the part she hasn’t talked about very much.

“I am working on being more open,” she says. “It is a large part of my story, but it needs to be told correctly.”