In 1989, a new faculty member’s chance discovery on a library shelf at Western would set in motion three decades of work and help solve one of the biggest anthropological and linguistic puzzles of our time: Where did the Indigenous peoples of the Americas come from?

Now, 30 years later, Professor of Modern and Classical Languages Edward J. Vajda has become internationally known for his historical linguistic research comparing the language families of Siberia and North America, and his hypothesis, increasingly accepted by fellow historical linguists, is based on clues hidden inside an ancient Siberian language called Ket.

For decades, scholars speculated whether any of the languages spoken by the First Peoples of the Americas could be related to languages of the Old World. Before the arrival of Europeans, there were at least 120 Indigenous language families spoken from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego on the southernmost tip of South America. The well-known Nahuatl language of the Aztecs and the Quechua language of the Incas were only two of perhaps 1,500 individual languages once spoken across the Americas, but none of them had ever been definitively linked to languages in Eurasia or elsewhere.

Until now.

As it turns out, Vajda has found that one particular Native North American language family does appear to be linked with the Ket language of Siberia. The effort needed to investigate this—and have it accepted by the scientific community—has taken Vajda decades of hard work, two books and countless presentations, papers and journal publications, extensive fieldwork in Siberia, and, as is the case with most breakthroughs, more than a little luck.

More recently, his work has gotten the attention of archeologists, anthropologists, geneticists and other scholars who are also digging into Vajda’s theories about the language link between Asia and North America.

And none of it would have happened without that chance discovery in Wilson Library.

“It was totally random”

In 1989, third-year faculty member Ed Vajda was leafing through piles of books from Western Libraries’ expansive collection on Mongolia and East and Central Asia.

“I spent hours and hours with that collection,” he says, “so many hours.”

One day, while wandering a quiet aisle deep within the library, he thought he heard someone whisper his name, and he spun on his heel to see who it was.

The aisle was empty.

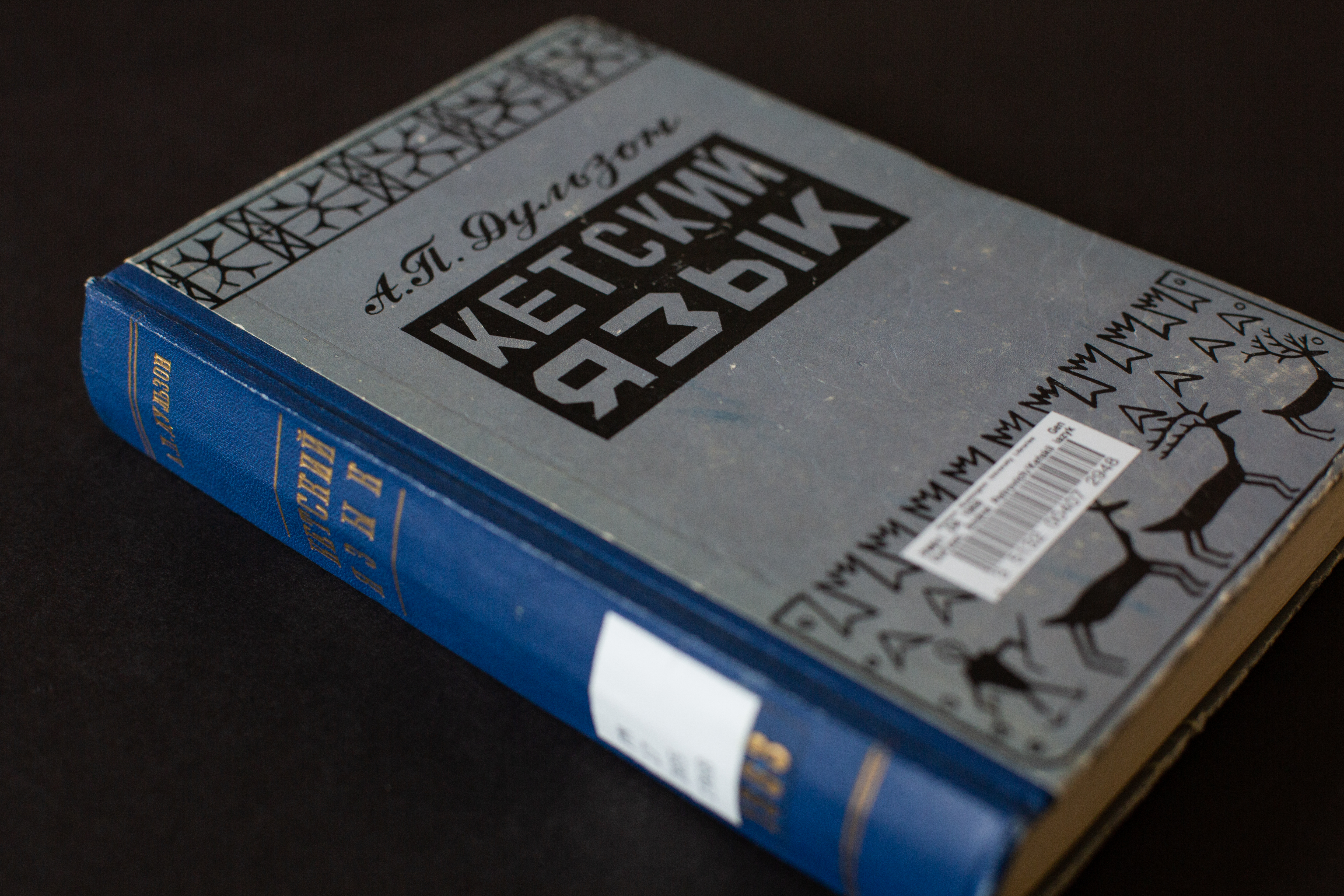

But there on a shelf was a book he had not seen before, with a title, “The Ket Language,” written on the binding in the Russian Cyrillic alphabet.

“The book was written by a former Soviet-era linguist, Andreas Dulson, who had been exiled by Stalin, and it was all about the linguistic uniqueness and complexities of a tiny group of hunter-gatherers in Siberia,” Vajda says. “The more I read, the more interested I became. If I had known I would be still poking down this rabbit hole 30 years later, maybe I would have put that book down and run,” he says, laughing.

“No, not really. I love it. It fascinates me. But finding that book—it was totally random.”

The Mystery of the Ket

The Yenisei River basin is a region in Siberia more than three times the size of France and Germany combined, and in its heart, surrounded by thousands of square miles of boreal forests and little else, are a few scattered villages where several hundred Ket people live today. Mostly devoid of rich deposits in ore or fossil fuels, the Yenisei river area in central Siberia has been passed over for centuries, first by the Turks and the Mongols—who couldn’t keep horses in the northern forests—then by the czars and the Soviets, the region still remains one of the most sparsely populated areas in Russia.

“It was too remote for Stalin to build gulags there,” Vajda says, “which tells you something.”

But this isolation, Vajda correctly surmised, had done one very important thing: By preserving Ket from linguistic replacement by larger outside groups, it froze the language in time, an apt metaphor given the Yenisei’s incredibly harsh winters.

Whereas the language families from regions surrounding the Yenisei had all been assimilated into larger families over the centuries, the Ket people, in their unique geographic and cultural bubble, had retained what was, in essence, an ancient language in modern times, and a look back into the languages of interior Asia 5,000 years or more ago.

Into the Yenisei

Vajda studied the works of the few scholars who had interacted with the Ket, and he began to wonder how an ancient language might be used to unlock questions about similar languages in North America—but he knew books could only get him so far. He needed to go and hear and speak Ket for himself and discover as much about the language as he could, as native Ket speakers were growing very rare, even in the Yenisei.

From 1998 to 2009, years after he initially began to study the Ket, Vajda flew back and forth across the world to study native Ket speakers, and in 2008 traveled to the Yenisei, becoming the first Western linguist to interact with them.

“It only took seven planes, three trains, and a four-hour helicopter ride to get there,” he says.

Flying over mile after mile of impenetrable taiga, bottomless bogs and wide, braided rivers, it was easy for Vajda to see how the Ket had remained isolated for so long.

The time he spent in the field along the Yenisei gave Vajda ample new information to understand how the Ket language was structured and how it may have developed over time. He was now viewed as one of the world’s foremost Ket scholars.

But still missing were many disparate pieces of the puzzle that could show a complete picture of the relationship between the languages of Siberia and Indigenous Americans.

His expertise in linguistics could only get him so far. Although he possessed a sort of “decoder ring” with his knowledge of the Ket, he needed more tangible physical and biological evidence to continue to push his theories further.

But where could he get it?

Show your work

In 2008, with years of fieldwork under his belt and having become internationally known for his work on the Ket, Vajda presented the keynote at the first-ever Dene-Yeniseian Symposium at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks.

There, he laid out in full a hypothesis he had been working on for nearly 20 years, and continues to refine and update today: that there is a genealogical relationship between the Ket people and the Dene (Athabascan) family of peoples of North America, which along with Tlingit and Eyak form the larger Na-Dene family. Vajda traced this relationship by finding common root words and grammatical patterns shared by both families. Finally, a long-sought connection between Siberian and North American language families had been made, sending shockwaves across the linguistic and anthropological communities. Could two peoples half a world away from each other really be related?

Vajda had taken it as far as he could with linguistics. It was time for other scholars to help fully connect all the dots between Siberia and North America.

Clues emerge

Vajda had begun to work on a theory involving relationships he was seeing emerge between the Ket and the Na-Dene at about the same time as other scientists were, either directly or indirectly, working along the same path.

Archaeologists and anthropologists had been finding more evidence about who came across the Bering Sea land bridge that connected Asia and North America, information that began to open new doors for Vajda.

“It was long assumed that the major pulse across the land bridge from Siberia to Alaska happened about 14,000 years ago,” Vajda says. “But new findings were showing that there had also been a second, smaller pulse that began about 5,000 years ago. Who were they, and what languages did they bring with them?”

The possibilities were tantalizing.

“We thought this could be the link to the Na-Dene we had been looking for, and in the end, it was,” he says.

By now, researchers knew the initial pulse across the land bridge, brought the First Peoples. Before their arrival, humans hadn’t yet settled the Americas, as far as is known. But within less than a thousand years, the First Peoples traveled from the Aleutians to Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South America, with groups settling down to become what we know today as everything from the Haida, Coast Salish, Iroquois and Cherokee to the Incas, Aztecs, Toltecs and Mayans, as well as hundreds of other distinct tribes.

Vajda says that archaeologists had already determined that the newer pulse across the land bridge started about 5,000 years ago; these people spread into the Arctic regions of Alaska, Canada and Greenland. Their descendants, or perhaps their modern cousins, are known now as the Aleut, Inuit and Yupik peoples. However, there was no archaeological evidence these northern Asians also mixed with the First Peoples ancestors of the Na-Dene about 5,000 years ago, so demonstrating a link between the Na-Dene and the Ket remained elusive.

Genetic Codebreakers

As it turned out, it was geneticists, not archaeologists, who showed that the second group from about 5,000 years ago apparently had turned south and settled alongside pre-existing bands of the First Peoples in what is now Alaska, the Yukon, and the Northwest Territories. And according to Vajda, they joined with the people already living in the interior to form the Na-Dene, whose genetic profile is composed of the First Peoples along with newcomers from northern Asia.

Some of the Na-Dene would stay in the Alaskan interior, while others would go on to migrate south and become the Tlingit, the Navajo, and the Apache, but the code to unlock the origins of their languages have one common denominator—Ket.

“Ket was the key, and it finally unlocked it all,” Vajda says.

But to fully prove the theory and get buy-in from across the scientific community, Vajda needed more—so he began working with Pavel Flegontov, a biologist and geneticist at the University of Ostrava in the Czech Republic.

Flegontov says that like Vajda, he was drawn to the conundrum of the Ket and the Na-Dene, although he was approaching it from a completely different angle.

“Like Edward, I started to work on the Ket just by chance. When in 2013 I got an opportunity to lead an independent research team looking into human prehistory, I happened to hear from a friend in Moscow who headed a sequencing facility that they planned to sequence the genomes of the Ket people,” Flegontov says. “With this data, we were then able to show that Kets, along with Selkups and Nganasans living on the Yenisei, belong genetically to a certain sub-group of Siberians closely related to Paleo-Eskimos that crossed the Bering Strait about 5,000 years ago.”

Vajda says the data unlocked by Flegontov finally brought all the pieces of the puzzle to the table.

“Pavel began testing DNA, and what he found was two-fold: that the Na-Dene have a genetic base of the First Peoples mixed with a minority component derived from the newcomers that crossed Bering Strait, and that genetically the Ket are linked to this same group as well,” he says.

“Finally, almost 30 years later, there it was,” Vajda says with a long sigh, as if the retelling of this long tale of research and discovery had reminded him of the arduous nature of the task he set before himself when he first discovered the book in Wilson Library in 1989.

The research of Flegontov and Vajda was published in the June 13 issue of Nature, one of the world’s foremost scientific journals, and this recognition is the metaphorical cherry on top of three decades of hard work.

But when asked if he was ready to close the book on the Ket and the Na-Dene, Vajda’s response and his trademark grin were typical.

“Oh no, not at all. I think we’ve only just gotten started.”