Nobody ever said saving the planet was going to be easy.

It was not the case in those now quaintly dreamy, Age of Aquarius days of the early 1970s, when Western’s Huxley College of the Environment was founded as a unique way to produce graduates with both the technical chops and policy skills to solve—not just complain about—pollution and other social ills.

And it clearly is not the case now, about 7,800 graduates later. The world’s first interdisciplinary environmental college celebrates its 50th year by acknowledging a renewed urgency for those skills in an increasingly desperate bid to combat global climate change—or blunt its human impacts.

That evolution in the need for students imbued with Huxley’s real-world problem-solving skills in many ways reflects the evolution of environmentalism itself: At Huxley’s 1970 founding as a “cluster” college beneath the Western Washington University umbrella, “going green” was a distinct movement – a product of social activism spawned in the 1960s, and played out in subsequent years with the establishment of Earth Day, and the launching of federal laws and programs focused on cleaning up and protecting the air, earth and waterways.

Its advocates, many of them graduates of Huxley and a small handful of counterparts, ultimately succeeded in making environmental consciousness part of accepted social norms. In contrast to the national norm at Huxley’s founding, environmentalism has been “institutionalized” in many segments of American life, author and journalist William Dietrich notes in “Green Fire,” his rich history of the Huxley program at age 40.

Local and national recycling programs, standards for energy efficiency, clean air and water, toxic contamination and other pollution, and even the way we build structures all owe their existence to public acceptance of giving the planet’s health, while clearly not primacy, at least a seat at the table of civic life.

But it’s safe to say that none of the dreamers who launched Huxley College (inspired by and named for Darwin-defending biologist/anthropologist Thomas Henry Huxley, not his more-famous relative, the writer Aldous) could have seen the need for students steeped in the Huxley way becoming so critical, so soon, in today’s climate-change reality.

In one sense, growing angst over a warming planet has been good for business at Huxley College.

“We live in a time where making a difference drives the college decisions of a lot of students. For us this has meant huge enrollment growth. We have more students than we have capacity in many areas,” says Steve Hollenhorst, dean since 2012 and parent of a Huxley graduate.

Huxley’s faculty—roughly 42 tenured and 40 non-tenured professors—now offers some 200 courses in the biophysical sciences and social sciences related to environmentalism to more than 1,000 students. The program’s areas of emphasis have become increasingly specialized.

The urgent need to address climate change, Hollenhorst says, has been more transformational than any other single force since the college’s birth a half century ago.

“It conditions everything we do now,” he says. “It is the global lens that we have to look through.”

Other societal shifts, especially a recent focus among incoming students on social justice issues, which translates to environmental equity in Huxley courses, also have led to major curricular adjustments, he notes, and will continue to do so. “But making progress in these critically important areas is all the harder because climate change has sucked up all the oxygen,” he says.

The accelerating planetary warming crisis is so frontloaded on the psyches of incoming students that “climate fatigue” and “climate despair” have become pressing issues for freshmen, now mostly born since 2000. Faculty at Western and other U.S. institutions have scrambled to combat this battle against deep-seated hopelessness.

“They are both agitated and motivated about this,” Hollenhorst says. “I see our faculty thinking more and more about how to help them out with hope, and with more of a positive approach.”

Part of the value of higher education in general, and Huxley’s programs in particular, is that it provides a hands-on outlet to combat stress by actually working the problem, Huxley faculty members say. That’s an outlet not every young person has.

“I think it’s really all about, ‘OK, here’s how we can work on this,” Hollenhorst says. “Climate, it’s really just math. We know what we need to do! You can take these energy courses. And here’s how you can make these new buildings carbon-neutral. That’s pretty powerful, and we can send these students out with those kinds of skills.”

The climate-change focus has manifested itself in other visible ways inside Huxley’s concrete, Brutalist- themed headquarters in the Environmental Studies building on South Campus. Its curriculum has both expanded and substantially shifted gears to address it.

Huxley is deeply involved with Western’s Institute for Energy Studies, the first in the country to offer a bachelor’s degree with that distinct area of focus, Hollenhorst believes. “The keystone approach to the climate problem is energy,” Hollenhorst says. “We’ve created 30-some energy courses; climate is the rationale for every one of those classes.”

“There are dozens of courses in place there, and virtually every one of those courses is climate-solutions oriented,” he says. “So there’s hope embedded in that.”

Climate and Social Justice

The renewed emphasis on that issue from incoming students is also piggybacking on another major Huxley trend long underway—the shifting of intended career paths beyond traditional employers such as government, recreation, conservation and planning agencies into the private sector.

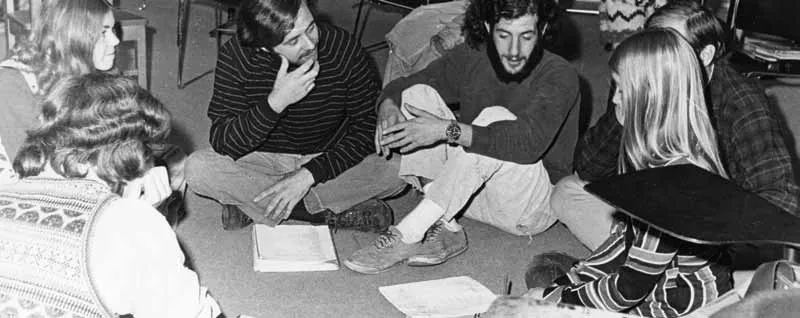

Students in the founding groups of Huxley students were largely activists in a relatively tight-knit social group that literally lived together, sharing housing, food and other life necessities. Many either drifted into the program to fulfill a broadly defined passion, or intended to qualify for jobs in research or government.

“That’s all changed,” Hollenhorst says with a chuckle. “Today a student will come to Huxley, look me in the eye and say: ‘I want to go to work on greening Costco’s supply chain!’ In my generation, we never would have thought of working for corporate America. That’s not what an environmentalist did. Students today know that’s part of the solution.”

Result: Rather than sneer at one another across campus, Western’s Huxley and College of Business and Economics now enthusiastically collaborate. Students demand it; Western’s Business & Sustainability major is a tangible result.

Even so, Huxley hasn’t abandoned its traditional mission of blending biophysical sciences that identify and quantify environmental problems with the social sciences necessary to form private and public-policy solutions. That problem-solving focus embodied in curriculum has led to a raft of tangible environmental solutions, including local success stories such as land-use regulations around Bellingham’s drinking water source, Lake Whatcom.

“There’s still people teaching about rivers,” Hollenhorst notes. “There’s still people teaching about environmental education, teaching about land law and water law. But now, climate is interjected into all those conversations. You can still focus on the things you love. But there’s a climate lens, and there’s a social justice lens.”

The latter focus is intertwined with another area of emphasis spotlighted at Huxley in the past decade: what is viewed as a critical need to diversify the student body and faculty in a field of study which, in America, has long been overwhelmingly white. A more-diverse Huxley College alumni is better poised to address likely looming challenges of environmental justice – the equitable sharing of consequences of, and the burden of addressing, climate change.

“It’s not just something we struggle with in Huxley, but rather is an indictment of the entire environmental movement and environmental community,” Hollenhorst says.

Environmental organizations continue to be an “overwhelmingly white ‘green insiders club’” with very little inclusion of people of color, according to data gathered by Green 2.0, which advocates for inclusion and diversity in environmentalism.

“It’s probably a lot of different factors,” Hollenhorst says, “But the language we use, the subjects we study, the discourse we engage in, the research we conduct, has not been as inclusive of the breadth of environmental issues, particularly those facing marginalized sectors of our society, as it should be. That’s on us. We need to find ways to be better at this.”

A 2015 Huxley study laid bare the scope of the task. Fewer than 1 percent of Huxley students were African American; only 0.6 percent identified as Native American; 2.6 percent Asian, and 6.4 percent Hispanic or Latino. All of those numbers were lower than comparable populations in the state, in Bellingham, and among Western’s general student population.

Today, the total percentage of students of color is about 21 percent at Huxley, compared with overall WWU enrollment of 26 percent at Western. But the growth in students of color at Huxley still lags behind the college’s overall growth, says Shalini Singh, Huxley’s diversity recruiter and retention specialist.

In keeping with a similar effort underway—and showing some successes—campus wide, Huxley has launched a multi-pronged effort to enhance diversity. It brought Singh on board, and the college has made it a priority to boost the diversity among staff, faculty and students and to cultivate an inclusive academic environment. Administrators already working to secure funding for Huxley amidst historically declining levels of state budgetary support have spent more time focusing on ways to attract funding to provide access opportunities to prospective students in underrepresented communities. Existing scholarships have been refocused with that goal in mind; new ones are on the drawing board and seeking financing. Faculty and staff hiring protocols also have been remodeled, mostly to broaden job descriptions as a means to attract more diverse candidates, Hollenhorst says.

Much of this work is energized by the students themselves, says Singh, who is amazed by students’ willingness to take on additional responsibilities, on top of heavy course loads and work schedules, to help guide inclusion efforts.

“They take on these initiatives, knowing they may never get to see the results they’re hoping for during their time at Huxley,” Singh says. “But they work on them knowing they may be able to leave behind a legacy for future Huxley Students.”

One way Huxley has already made significant strides in that direction—enhancing not only the cultural diversity of its student cohort, but its economic and class diversity—is by establishing branch degree programs in Everett, Poulsbo and Port Angeles, employing community colleges as home bases for what become four-year bachelor’s degrees.

Beyond Bellingham

As Huxley celebrates its 50th, the Huxley College on the Peninsulas program is gearing up to bake its own 25th-anniversary cake. Graduates of those programs, which offer bachelor’s degrees in environmental policy and environmental science, already are inculcating Huxley environmental principles into local communities. Many are older, returning, single parent or other non-traditional students who say they would never have been able to realize those life dreams without programs that allowed them to study near their suburban or rural homes.

One of them is LaTrisha Suggs, 50, of Port Angeles, a 2002 graduate who was working two jobs to support a young son when she heard about a fledgling two-year Huxley program launching at Peninsula College. She jumped at the chance, attending evening and weekend extension courses while working 55 hours per week, earning her degree in two years.

As part of that program, she served an internship with Clallam County, researching septic systems along the Dungeness River. A member of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, she was hired after completion of her degree as assistant director of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribal team working on the monumental, and historic, project to remove two derelict dams on the Elwha River, the largest such watershed-restoration project in the nation. She now works as the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe’s Habitat Restoration Planner, a job that largely entails purchasing privately owned tracts of land in floodplain areas of the Dungeness, where her work began.

“Full circle,” she says. But hers keeps expanding.

Active on many other community boards and associations, she recently was appointed to fill a two-year vacancy left by the death of a Port Angeles City Council member. City officials believe she is the first Native American—and possibly the first nonwhite person—to serve on the council since it was established in 1890.

“I got lucky,” Suggs says. “I was a single mom. Being able to go off to a university wasn’t in my future.”

Today, as a mother of three and grandmother of two, she eyes a future in public service that she says would not have been possible without Huxley’s outreach. Port Angeles is growing in positive directions both culturally and economically, she says, and like many other rural areas is launching its own efforts to combat local effects of climate change.

“I’m just fortunate to be smack in the middle of it all.”

Other program graduates offered similar sentiments. While it’s distressing that the need has become so critical, so fast, Huxley has succeeded in seeding the local government, for-profit and nonprofit infrastructure with influential people possessing the skills to at least begin to tackle overwhelming problems in small, ultimately constructive ways, they say.

It’s constantly on the minds of Huxley grads such as Amy Lucas, a 2012 graduate of the Everett CC Huxley program who now works as a senior planner for Snohomish County Parks and Recreation.

“This is a crisis, yes, but there are things we can do, in moderation, right now to help mitigate all the impacts,” she says. “A lot of people think they need to do a complete 180 in their lifestyle, and that all solutions will be really expensive. But really it’s about small victories—baby steps. My soap box is moderation. Small changes can make big impacts—if we all make them together.”