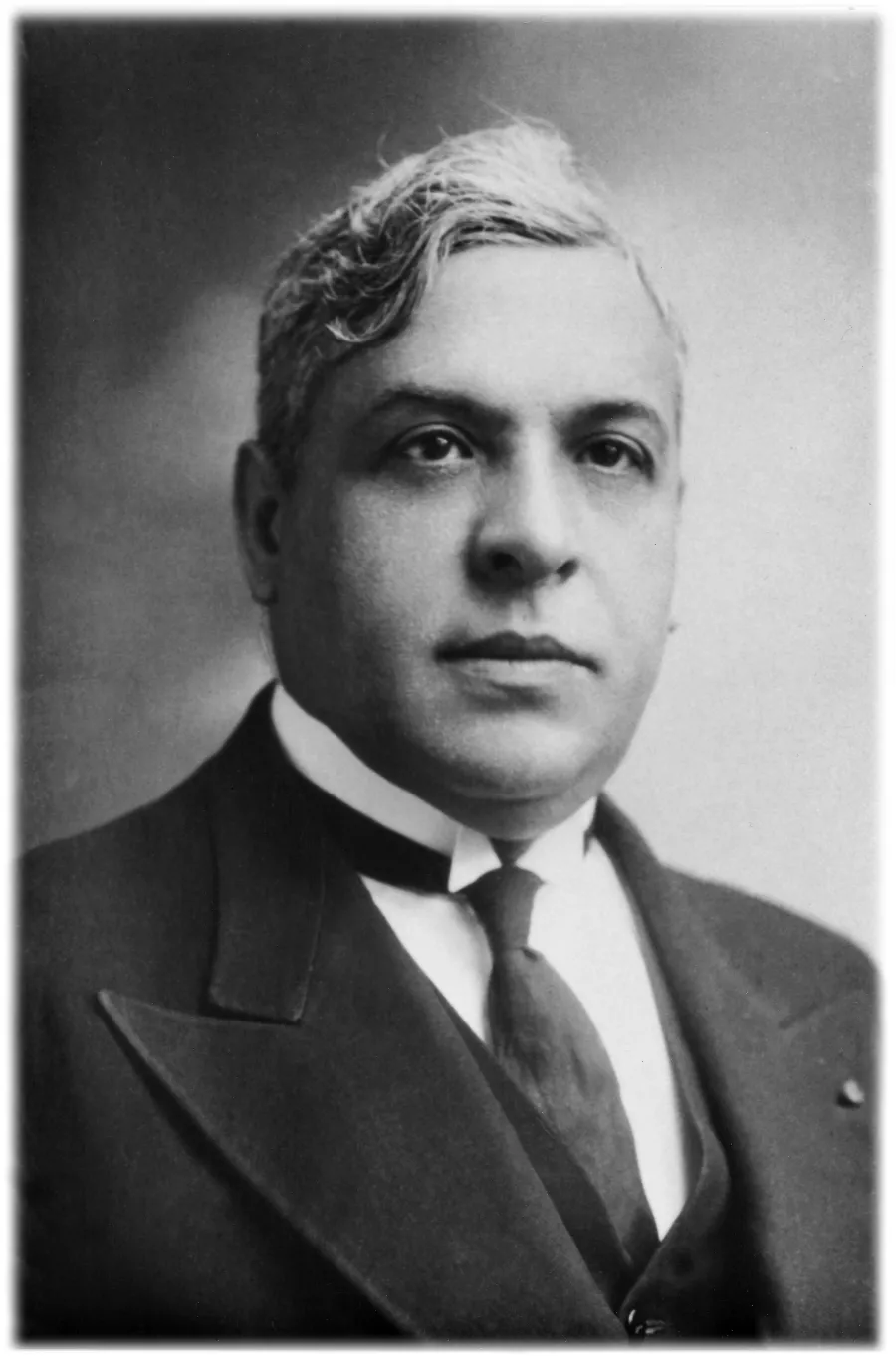

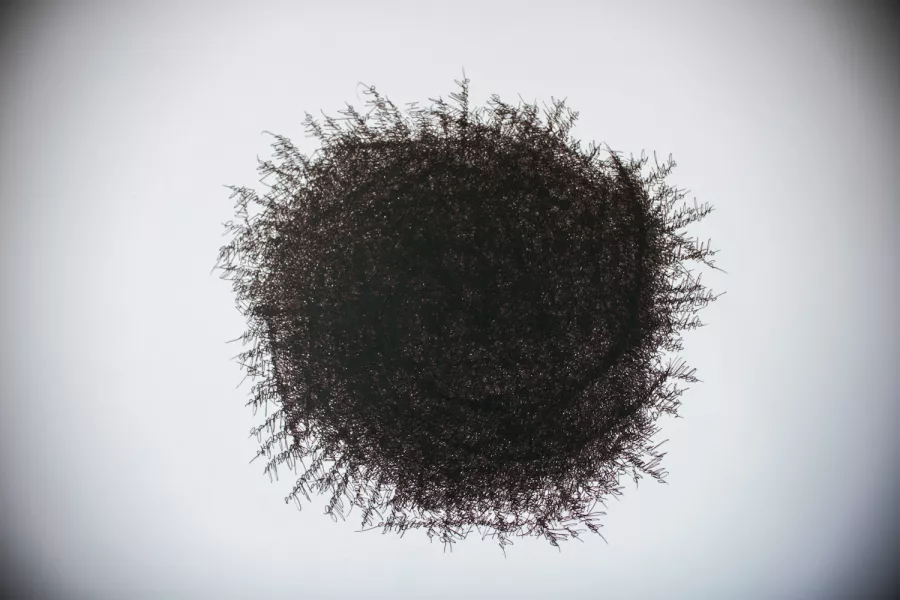

Overlapping tightly, densely packed, superimposed, the names are a palimpsest, a tribute to Aristides de Sousa Mendes, a man who changed history by defying his government and saving thousands from Nazi persecution.

“I had always been impressed by the fact that my grandfather had written visas for 30,000 people,” says Mendes, avant-garde artist and professor of Art who has taught at Western since 2001.

By the time he was 5 or 6 years old, Mendes became aware of his family legacy. He had heard about it in adult conversation, as relatives would come to his home in the Bay Area and discuss Sousa Mendes, not only unrecognized for his heroism by his home country of Portugal but actively ostracized because of it. Sousa Mendes, disgraced and penniless, had died in Lisbon in 1954 in total obscurity.

But to Mendes, visa recipients like Norbert Gingold, a virtuoso pianist who went on to found the San Francisco Youth Symphony Orchestra, were normal visitors at his family home. Mendes says, “I just remember it was part of the oral history of the family.”

Mendes, whose interest in art developed in high school and flourished during his time as an undergraduate at the University of California-Santa Cruz, says, “I thought, sometimes, every so often, that I would like to do something to pay homage to my grandfather as an image or as a work of art. I wasn’t a traditionalist.

The art I had in mind was more experimental, the avant-garde and so forth. So I didn’t have any interest in making a drawing of or a painting of the teeming masses or a portrait of my grandfather. That wasn’t what I was interested in as an artist. But I hadn’t formulated a project that was resonant for me.” Only after he’d completed graduate school at Stanford University did Mendes start developing what would become a signature style. As a faculty member at the University of Oklahoma School of Art, very conservative at the time, Mendes felt he couldn’t speak openly about his progressive political beliefs. He began rereading and writing out works verbatim that he felt were important in a complex, superimposed style. His palimpsests, pages with lines of text layered on top of each other, began as a way to publicly present what was private, to hide in the open with text indecipherable to anyone but himself.

An act of conscience

In 2004, he created his first drawing in homage to his grandfather’s heroic act, with 2,000 superimposed names, shown at an exhibition at Oregon State University.

Mendes then decided to start a series, 30 drawings with 1,000 names each. A thousand, he says, is a more fundamental, meaningful number. Done privately and in his Bellingham studio, these drawings became a powerful way to contemplate and engage with his grandfather’s story, a reflection, he says, and a secular prayer. He calls the collection “There Is a Mirror in My Heart.”

Ballpoint pen in hand, he contemplated family anecdotes, like how his grandfather, a member of the Portuguese nobility who served as a diplomat throughout Europe, Africa, and in the Americas, stood up at a banquet in Brazil in the 1930s. The toast was to Antonio de Oliveira Salazar’s new regime — Salazar, who’d recently taken power in Portugal, was a man no one would have dared to publicly call out as a dictator — and when everyone sat down, Sousa Mendes remained standing. He toasted the monarchy, an unthinkable act. His small rebellion caused him to be recalled to Lisbon for a reprimand. But this act of conscience would foreshadow his role in the war to come.

As the Nazis advanced across Europe, Salazar, officially neutral but unofficially pro-Hitler, issued Circular 14, a directive to Portugal’s diplomats to deny safe haven to refugees, explicitly to Jews, Russians and others who could not return to their countries of origin. Sousa Mendes, the Portuguese diplomat in charge of visas in Bordeaux, couldn’t ignore the plight of the 120,000 refugees who’d fled Nazi persecution. Turned away from Portugal’s borders, many had seen family die, had lost everything, and were confined to a field of three city blocks without access to food, shelter or sanitary facilities.

Visa assembly line

Sousa Mendes decided to defy Salazar’s orders, orders he believed violated the Portuguese constitution and his own deep Catholic faith, and his act inspired other consular officials, Manuel de Vieira Braga in Bayonne and Emile Gissot in Toulouse, to defy their government. José de Seabra, Sousa Mendes’ consular staff member, acted under Sousa

Mendes’ orders, playing an important role as well. Rabbi Chaim Kruger, collecting passports and delivering them in batches, worked with Sousa Mendes so that he could issue visas faster, as he attempted to issue as many as he could while he still had the authority.

The recipients, terrified of losing their places in line, waited for days and nights without eating or drinking, washing or changing their clothes, in order to gain access to the consulate. Then, they watched as officials jammed their visa forms into boxes and sacks, and brought them upstairs. Fees were waived for the recipients who couldn’t pay. Sousa Mendes worked furiously, fervently, signing as many as he could before he could be stopped.

As a performative act of social engagement and live art, Mendes tried to recreate his grandfather’s heroic act by publicly signing 30,000 names during an exhibition at the University of New South Wales in 2008, themed “Marking Time.” While Mendes sat there, drawing and explaining his work to a fascinated, international audience, he could feel that ticking clock. He says, “I was fully aware of time, the passage of time, the urgency of time, in terms of what my grandfather did. In those five days, I didn’t come close to 30,000. I think I only had 2,000, maybe 2,500. At first I thought it was a failed project. Then I realized it was an invitation, to make this project ongoing.” He has since added to the piece during performance art in New York, in Melbourne, Australia, and in Paris and Bordeaux, France. Currently, the drawing includes slightly fewer than 6,000 names on a 7-foot by 7-foot sheet of paper.

But this massive drawing, which may never be finished, very much highlights the immense scope of Sousa Mendes’ act. Mendes relates a story, told to him by a family member, about the deep sense of urgency to produce so many visas in such a short period of time. “First of all,” Mendes says, “they used up all of the consulate’s visa forms. Then, once those were gone, they started using a rubber stamp and putting it on all the plain paper they had at hand. But they ran out of that. So they started putting it on shopping sacks, tearing open paper shopping sacks. When they ran out of those, they used wallpaper.”

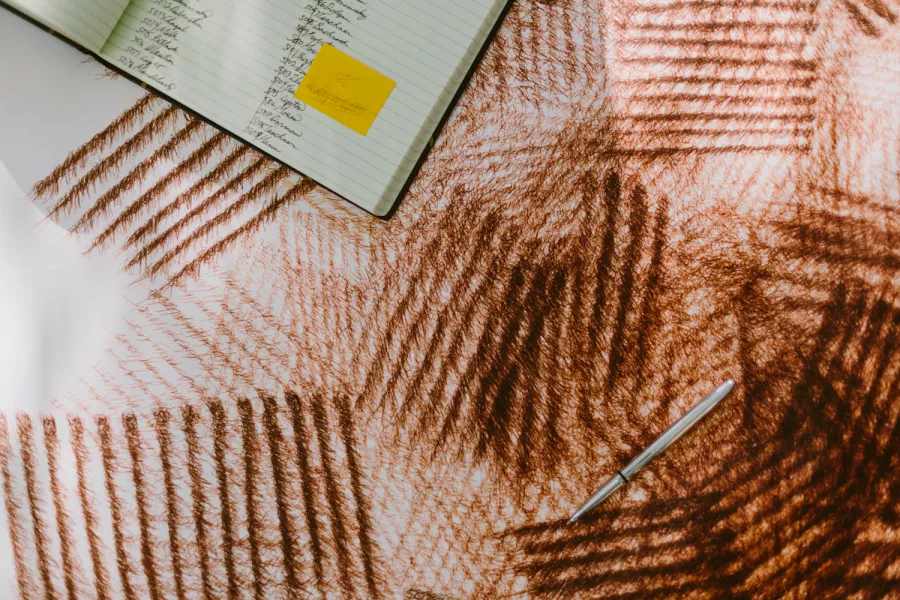

Mendes is acquiring vintage wallpaper to incorporate this family legend into his next series of drawings, so that these old patterns mingle with the names of those Sousa Mendes saved. He uses ledgers to keep track of the names he uses in his work. His grandfather, too, had ledgers in which he wrote the names of the recipients. “They’re pretty similar,” Mendes says. “Numbers, names, and all that. I like that.”

Only one Sousa Mendes ledger has been recovered. That means that less than 5,000 names of the 30,000 recipients are known. More names of recipients, and their descendants, are being discovered every day by the Sousa Mendes Foundation.

When the visas were brought out in Bordeaux, Mendes relates, the recipients’ names were called; they had no idea of what was happening behind the scenes. Mendes says, “They only knew that someone had given them a visa from Portugal. The younger kids, they never knew.”

The visas gave the families passage to Lisbon, where they could book passage to safety. Recipients included Archduke Otto von Habsburg, Emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, who would have likely been executed by Hitler if it were not for the visa from Mendes. Other notable recipients included artist Salvador Dali and his wife Gala, H.A. and Margaret Rey, who created “Curious George,” and married actors Madeleine Le Beau and Marcel Dalio, who later went on to play in “Casablanca.” Michel Gill, an actor from “House of Cards,” only found out recently, Mendes says, that his father and grandfather were recipients, too.

An aftermath in obscurity

Sousa Mendes never regretted the price he paid for disobeying his government’s orders, but he and his large family paid dearly. Ostracized in Portugal and unable to earn a livelihood, Sousa Mendes became so impoverished by 1942 that he and his family took their meals at a Jewish soup kitchen in Lisbon. His children, too, were denied access to employment and university studies in Portugal, and many emigrated to other countries in order to survive. Sousa Mendes died in 1954 at the Franciscan Hospital for the Poor in Lisbon and his 19th century mansion, the Casa do Passal, was forfeited to a bank.

In 1995, the Portuguese government finally posthumously recognized and celebrated Sousa Mendes’ act of heroism. Sousa Mendes was also the first diplomat to be recognized by Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, as Righteous Among the Nations, in 1966.

Mendes intends to continue his work on his grandfather’s legacy through an upcoming artistic video project, where he takes “video stills” of Sousa Mendes visa recipients and their descendants. Mendes says, “These video stills are something of a hybrid between traditional portrait photography and the movement of a live video image.” He’ll make these video stills as he retraces the refugees’ route on a journey that begins in Bordeaux, crosses through Spain, and includes such important destinations as the restored Casa do Passal in Portugal.

Even though Sousa Mendes may have died unrecognized and unknown, by celebrating his grandfather’s story through his artwork, Mendes urges us to recognize that his grandfather’s legacy lives on—not only in his many descendants, but also in the visa recipients, and their descendants, those he saved.