In the realm of honorary gestures, it might seem minor—particularly for a man already awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor. But to the family of former Western student James K. Okubo—and the current community of Whatcom County Japanese Americans—the June granting of the university’s first posthumous degree to a once-forgotten war hero was a landmark event.

Okubo was a promising sophomore, an aspiring dentist, at Bellingham’s Western Washington College of Education in 1942 when he and his family were ripped from well-established Bellingham lives during the wartime incarceration of citizens of Japanese descent. Seventy-seven years later, Okubo’s family, at a June graduation ceremony, gratefully received the degree he never had a chance to complete.

“I thought it was a very kind gesture, making reparations for the past,” says Anne Okubo, 64, daughter of James Okubo, who died in 1967. “That’s not really the responsibility of the current generation. But the current generation needs to understand the history, so we don’t repeat it.”

A star athlete at Bellingham High School and the son of Kenzo and Fuyu Okubo, who operated the Sunrise Café on Holly Street, Jim Okubo was denied the chance to fulfill his dream of graduating from his hometown college. After spending 11 months at the Tule Lake camp in California, Okubo enlisted in the U.S. Army, where he earned multiple medals for valor while serving as a medic.

His wartime exploits were rediscovered in the late 1990s, thanks to a review of military records of Asian American veterans. Okubo was posthumously granted the Medal of Honor by President Clinton in 2000 for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.”

His story has taken on new life, amidst a flurry of remembrance of the incarceration of Japanese American citizens nearly eight decades ago, and caught the eye of members of Western’s campus community. Fittingly, the 2011 Washington legislation enabling regional universities to grant honorary degrees (nine have since been granted) also authorized degrees for students removed from college during the incarceration of Japanese Americans, notes Paul Dunn, Western’s chief of staff and secretary to the Board of Trustees.

Two Western employees of Japanese descent, Carole Teshima, ’94, B.A., Fairhaven interdisciplinary concentration, and Mark Okinaka, ’15, MBA, nominated Okubo for the honorary degree. Okinaka had reviewed the hand-typed books of enrollment records from that era, searching for students who may have faced incarceration in 1942. Okubo appeared to be the only full-time student forced to leave Western after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the now-infamous Order 9066, authorizing the incarceration of West Coast citizens of Japanese, German, and Italian descent, on Feb. 19, 1942.

Okinaka’s own father, uncle and grandparents were incarcerated at the Manzanar and Tule Lake camps. His father and brother both went on to serve in the military, his father in the U.S. Army for 30 years, including time in the Vietnam War, and his uncle in the U.S. Air Force.

Mark Okinaka followed in the family tradition and served in the U.S. Army during the Persian Gulf War. Last year, he told Okubo’s story at Western’s Veteran’s Day assembly.

Teshima’s heart leapt when she received word that the degree application for Okubo had been approved. Helping bring honor to Okubo and other Japanese Americans imprisoned in camps during World War II, she says, “is one of the great thrills of my life.”

Teshima, a former Bellingham Herald news librarian, has become Whatcom County’s go-to historian of local citizens of Japanese ancestry. She’s a member of a local group of about two dozen Sansei, or third-generation Japanese Americans, many of whom had parents and or grandparents incarcerated during the war. (U.S. immigrants born in Japan are referred to as Issei; second-generation family members, such as James Okubo, are Nisei, based on Japanese numerals.)

Her father, George M. Teshima, served in a separate company of James Okubo’s WWII Army regiment, fighting in Italy and France and earning a Purple Heart. Her great aunt and her family were sent to a Canadian incarceration camp in British Columbia.

Acceptance, then feverish suspicion

Starting with data on Northwest Washington Asian immigrants compiled in 1982 by University of Washington anthropology researcher Margaret Willson, ’79, B.A., ’82, M.A., anthropology, Teshima has fleshed out the lives of most of the Japanese American families in Bellingham leading up to the war.

The first recorded instance of a Japanese person immigrating to Washington state was in 1880 in Walla Walla. A decade later, 81 Japanese immigrants had settled in Whatcom County, most arriving via British Columbia, Willson found.

By that time, Teshima notes, most earlier Asian immigrants, from China, had already been driven out of Whatcom by a torrent of racist sentiment. Many Japanese and East Indian immigrants filled their place in the local labor market. The first Japanese residents in Whatcom were mostly educated members of the Japanese upper working class, Teshima notes. Most sought to swiftly integrate, learn English, run their own businesses, and generally fit in.

In spite of ongoing anti-Asian sentiment in Whatcom County, Japanese immigrants for many years were more accepted, largely because they became active in the Bellingham business community. But latent racism resurfaced with the outbreak of war.

Teshima’s files are filled with government records and browning clips from local newspapers, documenting the stark transition from begrudging acceptance of local Japanese immigrants to feverish suspicion after the attacks on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

Most of this sprang from unfounded fears that citizens of Japanese descent were poised to commit acts of sabotage. Random arrests of “suspicious” local Japanese American citizens by Bellingham police occurred during the period, and drew little public backlash.

By the time of Roosevelt’s order, Japanese “internment” already enjoyed broad political support in the region. Gov. Arthur Langlie encouraged it, as did local elected officials. On Feb. 25, 1942, the Bellingham City Council approved a resolution calling for “the removal of all alien enemies, including American born Japanese, to concentration camps far removed from the Pacific coast.”

On June 3, 1942, the bus arriving to remove Whatcom’s Japanese Americans opened its doors at the Okubo residence at 1406 H Street, where family patriarch Kenzo Okubo had posted a “for sale” sign on the wall of the family home.

A story marking the event played on inside pages of the newspaper and was decidedly humdrum: “Whatcom County was without persons of Japanese extraction Wednesday afternoon,” the Bellingham Herald reported on June 3, 1942. “All resident Japanese here—thirty-three of them—left Bellingham Wednesday morning for the Tule Lake assembly center south of the California-Oregon border. Taking only their personal belongings, most of the departing Japanese traveled by chartered bus to Burlington. There they boarded a train for the Tule Lake center.”

In all, 97 residents of Whatcom, Skagit, San Juan and Island counties were incarcerated, most initially sent to the large Tule Lake camp, according to news accounts at the time. Another 57 were picked up by buses in Everett, hundreds more in Seattle and around Puget Sound.

None of the families removed from Whatcom County would ever return. Most were admirably gracious in their introduction to captivity, The Herald noted: “A majority of those ordered to the California assembly center from Whatcom County were born and reared in Bellingham and are citizens of the United States,” the newspaper noted. “They left their homes behind without complaint, one graduate of Bellingham high school declaring just before the bus departed: ‘Bellingham is the finest place in all the world.’”

Walled-off family histories

Okubo put on a brave public face, even making light of the pending incarceration. In an event memorialized by the campus newspaper, The WWC Collegian, Okubo was feted with an “evacuation party” by some of his Western classmates, at which he handed out gifts—leftovers, he said, from the family packing up for departure—including a Japanese newspaper and blackout paint.

Five months into his incarceration, Okubo reported back to the newspaper from his “relocation center” that the place was “nice,” but he longed for “some good Washington rain.”

That sort of outwardly understated response to a cataclysmic event was typical of incarcerated families, particularly the Nisei, Teshima and Anne Okubo agreed. It carried over to the post-war era, when most Japanese Americans, stung by the perceptions that they were not loyal Americans, endeavored to push the ugly incident into the past and move on.

The Japanese phrase, Shikata ga nai, translating to “it cannot be helped” or “nothing can be done about it,” sums up the sentiment of that generation, Teshima says.

The reaction from that generation was understandable, but proved unintentionally devastating to many of their children, Anne Okubo noted.

“That’s what the current generation needs to understand,” she says. “The story of internment, why it happened, and what it did to the Japanese community. It absolutely destroyed Japanese American culture,” particularly for the immediate next generation, she says.

Memories of the pre-war and war years were so thoroughly walled off by her parents that Anne Okubo realized only recently, through news stories, that her father had ever attended Western.

Singled out for valor

James Okubo, born May 30, 1920, in Anacortes, grew up as a member of a large extended Bellingham family that included six siblings, along with four cousins after the death of Fuyu Okubo’s sister.

An athlete and avid skier, James graduated from Bellingham High School in 1938, later enrolling at Western, which he attended until his family’s forced removal from Bellingham. He ended his stay at Tule Lake by joining the Army on May 20, 1943.

After basic training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, Okubo, then 22, was assigned as a medic to the soon-to-be-legendary 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a segregated squad of Japanese Americans. Committing to the war effort was a full family affair: Also enlisting were James’ two brothers, Hiram and Sumi, and cousins Isamu and Saburo Kunimatsu. (Isamu “Eke” Kunimatsu, also of the 442nd, was killed in Italy on July 12, 1944.)

The 442nd regiment earned fame in a daring October 1944 rescue of the U.S. Army’s “Lost Battalion,” trapped behind enemy lines in eastern France.

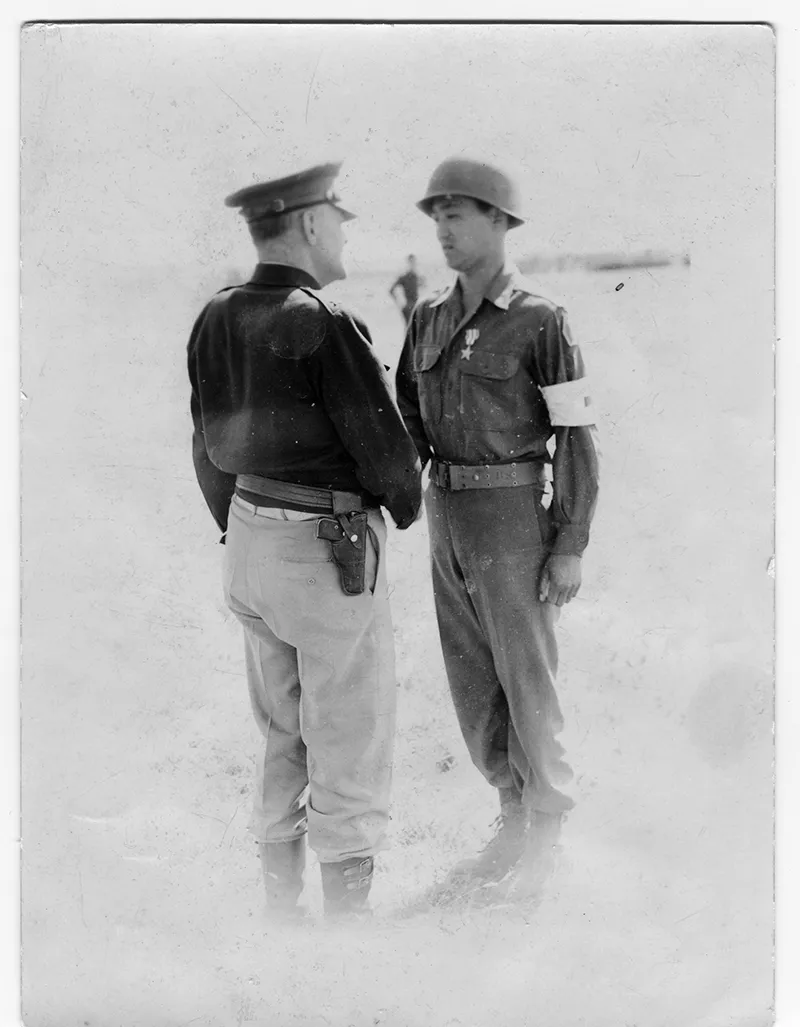

Okubo was singled out for valor: In a crucial battle, Okubo, dodging grenades and heavy fire, crawled 150 yards, to within 40 yards of enemy lines, to carry wounded men to safety, and personally treated 17 fellow soldiers. Days later, he ran through machine gun fire to rescue a comrade from a burning tank, saving his life.

In 1945, Okubo’s superiors nominated him for a Medal of Honor, but he received a Silver Star, perhaps because of a mistaken belief that it was the highest honor for enlisted medics at the time.

Okubo rarely spoke about his war experience, his daughter recalled. After the war, he reconnected in Detroit with surviving family members (his father had died at Tule Lake from pneumonia; other family members had been moved to a camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming). Okubo enrolled in Wayne State University, where he met his future wife, Noboyu Miyaya. The couple had three children, and Okubo finished dental school at the University of Detroit.

From then on, he practiced dentistry, including much pro bono work, taught at his alma mater, and conducted research, including early studies of links between tobacco and oral cancer.

“We didn’t see him much,” Anne Okubo recalls.

James Okubo, 46, was killed in car accident on a family ski trip near Flint, Michigan, in 1967. Daughter Anne was in the backseat of a car driven by her father. She recalls only occasional stories, mostly from her aunts, about the “camp” days, with little indication that it was forced incarceration.

Growing up in Detroit, her own generation was still struggling to suppress its Asian identity, she recalls. It wasn’t until she moved to Hawaii and became exposed to broader Asian communities that she realized what a hole that had left in her self-image—and how much ill-advised policies, such as the fear-based incarceration of her forebears, had contributed.

“It was something people were ashamed of, being Japanese,” she says. “It was a painful experience. People lost everything. It erased their whole heritage. The whole experience emotionally scarred them, making them risk-averse about being Japanese. That’s why my generation, the Sansei, was totally Americanized. We were discouraged from being Japanese. I grew up thinking I was white. It bore a large emotional toll on entire generations.”

As an adult, working in public health administration in the Bay Area, the mother of two adult children, and grandmother to one, she understands. People, loved ones, come and go too soon.

But their stories—assuming they are shared—live on. They have meaning.

Had he lived, James Okubo would have turned 99 shortly before the June graduation ceremony honoring him on Western’s campus. His story, his family believes, has meaning. Especially now that the university he once loved and called home has officially embraced it.

“I think it’s a pretty big deal,” says Anne Okubo, who looked forward to meeting members of Whatcom County’s reestablished Japanese American community for the first time. “It’s an honorary degree from a large university. People don’t get those every day. There have been other things, like buildings, named after my father. This is something different.”

For them, and for Western.