"Artistic Gifts" originally appeared in Window magazine in spring 2012.

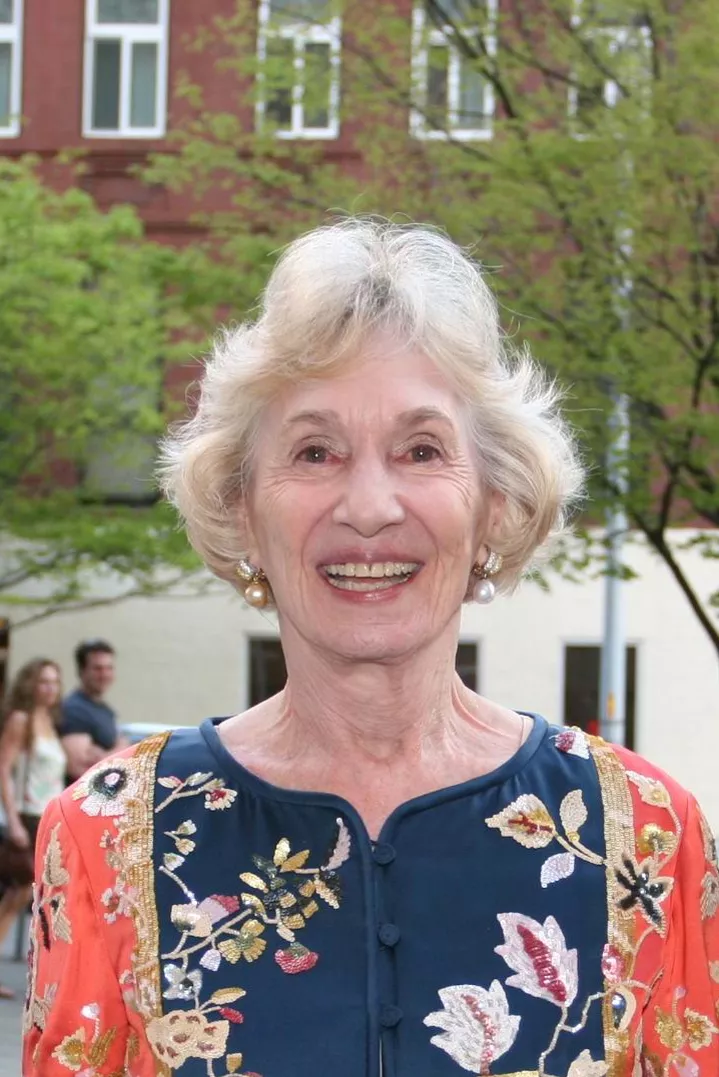

Virginia Wright passed away in 2020. Learn more about her life.

"Artistic Gifts" originally appeared in Window magazine in spring 2012.

Virginia Wright passed away in 2020. Learn more about her life.

How much art can you buy with a million bucks?

That was the question Virginia Wright faced in 1969, when her father, Northwest timber baron Prentice Bloedel, gave her a million dollar endowment and a mandate to buy public artworks for the region.

Mr. Bloedel’s gift came as a surprise: He didn’t really like contemporary art. But he knew what made his daughter tick – and that she had the passion, the knowledge and the connections to make his investment a pretty safe bet.

He was right. Since that time, the Virginia Wright Fund has reshaped the landscape of Northwest art and provided the driving force behind Western Washington University’s nationally acclaimed Outdoor Sculpture Collection. Of the collection’s 25 artworks, the Virginia Wright Fund purchased five and partially paid for two others. Six more works were donated from the Wrights’ private collection. Mr. Bloedel would surely be pleased.

If you have a lot of money, giving it away is easy enough. But if you want your money to make a difference, it takes vision, research, hard work and the guts to go out on a limb. Those are qualities that set that Virginia Wright and her late husband, Bagley, apart from the crowd and made them a power couple whose impact on this region’s cultural life began well before Prentice Bloedel endowed the Virginia Wright Fund. Their work has since extended far beyond it.

For starters, Bagley Wright was president of Pentagram, the corporation that built that quirky tower for the 1962 Century 21 World’s Fair. Who knew the Space Needle would become Seattle’s premier landmark? At a time when Seattle’s theatrical scene was nearly non-existent, Bagley helped found the Seattle Repertory Theater and served as its first president. He also served as board president for Seattle Art Museum, trustee of the Seattle Symphony and chairman of the heart defibrillator manufacturer Physio-Control from 1966 to 1980.

A Seattle native, Virginia was a budding art collector, with an art history degree from Barnard College and a job at Manhattan’s avant-garde Sidney Janice Gallery, when she met Bagley in the early 1950s. He was a recent Princeton grad, working as a journalist, who immediately set his sights on the brainy, attractive young collector, granddaughter of Northwest timber magnates R.D. Merrill and J. H. Bloedel. They married, started a family, and moved back to Seattle in 1955.

While her husband was busy raising buildings and running businesses, Virginia was raising the couple’s four children – Charlie, Merrill, Robin and Bing – and, step by step, building the Northwest’s premier collection of post-World War II art. (That collection is a promised gift to the Seattle Art Museum.) For a while, Virginia ran her own gallery in Pioneer Square, specializing in prints by blue chip New York artists. But it wasn’t until her father’s gift that she found the perfect channel for her education and her energy, she said: “It gave me a purpose, and it changed my life.”

The first outdoor sculpture Wright purchased was a snap: Barnett Newman’s stunning 26-foot tall, Cor-Ten steel “Broken Obelisk.” Virginia saw it, loved it, wrote a check for $100,000, and donated the piece to the University of Washington, where it still resides prominently in Red Square, a university icon. Two other versions of the sculpture exist: one at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the other at the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas.

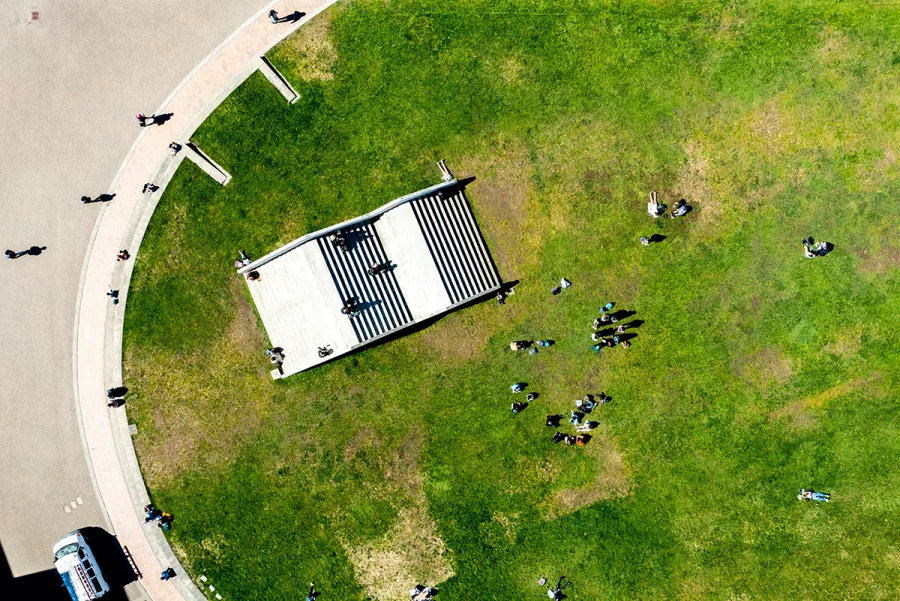

Then in the 1970s, Wright and her advisers turned their eyes toward the growing campus of WWU, which Wright saw as “a happening place” with a lot of pride, where some of the region’s best architects were designing new buildings. Some thought Wright was attracted to WWU because her father was born in Bellingham. Not true, she says. “It really was because the site was so beautiful. We fell in love with the campus.”

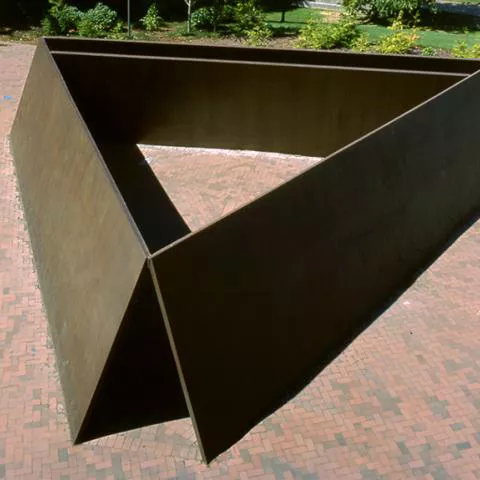

Wright began a conversation with faculty, administrators and then-president Charles Flora about donating a sculpture called “X-Delta” by an up-and-coming artist named Mark di Suvero. Response was enthusiastic. Agreements were signed. Then immediately the $40,000 deal started to go south.

Visit Western's Outdoor Sculpture Collection to see all the sculptures Wright donated or helped to bring to Western, including:

It turned out that “X-Delta” had been stolen! Or rather, as Wright tells it, while still in New York on loan to a “questionable” art dealer, the 11-foot-tall artwork had been seized to satisfy an unpaid debt. (The piece has since resurfaced and now stands on the campus of Dartmouth College.) The artist was at a loss on how to recover “X-Delta” and offered to create a new, site-specific piece for WWU in its place. That sounded like a great idea.

But one thing after another went wrong during the winter of 1975, and once the artwork was finally installed, a vocal group of students protested against it and circulated a petition to have it removed. They apparently thought the looming, abstract artwork of steel I-beams looked too industrial and interfered with the view (which at that time included Georgia Pacific’s pulp mill). Several students, swinging on the sculpture, brought a moving piece of it crashing to the ground.

It’s likely they didn’t know – or didn’t care – that during that same year di Suvero was honored with a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and had been the first living artist to exhibit his work at Le Jardin des Tuileries at the Louvre Museum in Paris. Public artworks rarely please everybody – at least in the beginning.

Wright herself was flabbergasted when she saw the enormous 27-by-36-by-64-foot sculpture titled “For Handel,” so different from the compact piece she had originally purchased. “It took my breath away it was so big,” she recalls. That experience taught her an enduring lesson about the gamble of commissioning artworks: “To the degree the outcome is different from your mental image, you can be exhilarated or very disappointed.”

But in this case, it turned out for the best. Wright acknowledges that the piece is “mind-blowingly good” and “For Handel” now holds pride of place as the centerpiece for the WWU Outdoor Sculpture Collection.

Part of Wright’s vision for the campus was to install a number of artworks in proximity, so that students and visitors could learn about 20th century art. Her next purchase was a steel sculpture by British artist Anthony Caro, donated to WWU in 1976. (Caro was knighted by Queen Elizabeth in 1987.)

At the same time Wright was working with Seattle Art Commission, the National Endowment for the Arts and other sources to commission Michael Heizer’s massive stone and concrete “Adjacent, Against, Upon,” for Myrtle Edwards Park on the Seattle waterfront. It stands near the Olympic Sculpture Park, which the Wrights were later deeply involved in planning, paying for and furnishing with art. And let’s not forget the Seattle Art Museum’s prominent “Hammering Man.” The Virginia Wright Fund chipped in a big chunk of the purchase price for that downtown landmark.

Wright says none of this could have happened without the enlightened support of university presidents Flora and, more recently, Karen Morse. Wright credits the success of the Outdoor Sculpture Collection to its longtime curator, Sarah Clark-Langager, whose excellent oversight has made the campus art collection a destination for visitors from across the country.

Recently, the Wrights added another targeted gift – a $250,000 donation that will enable the university to create two new galleries in the Performing Arts Center and renovate an existing gallery. The couple made the gift in honor of Clark-Langager, Virginia’s longtime friend. Sadly, Mr. Wright died last summer at 87, before he could see the results of that gift.

Through it all, Virginia Wright sees her experiences collecting and bestowing artworks as the time of her life. “It’s what I really love,” she said. “I can only look back on all that as kind of a joy ride. It was interesting; it got me in connection with a lot of interesting people. It was the best kind of fun.”