If you follow presidential election politics this year, you might conclude that Mexican immigrants are pouring into the United States without legal permission. You might also conclude that the number of immigrants living here illegally would be much greater if the U.S. weren’t spending $18 billion a year to keep them out.

In fact, neither is true, says Douglas Massey, ’74, professor of sociology and public affairs at Princeton University.

“Since 2008, illegal migration from Mexico has pretty much dropped to zero,” says Massey, who has studied Mexican immigration patterns for more than three decades.

For one thing, Mexico’s once stratospheric birth rate has plummeted, easing the population pressures that once drove immigrants north to the U.S.

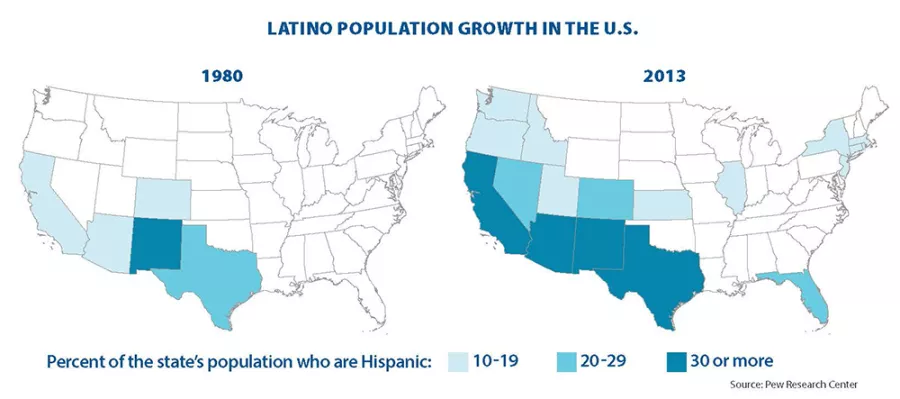

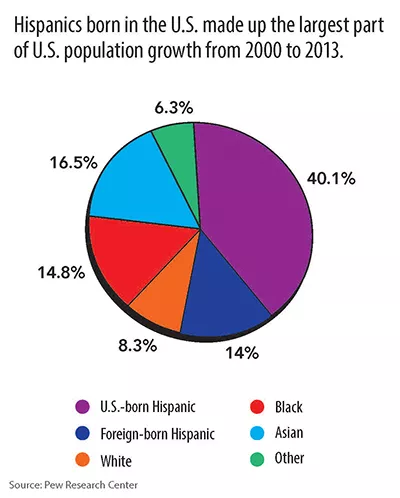

Even so, there has been a sharp increase in the U.S. Latino population – ironically due in part to the long-term U.S. government effort to stem illegal immigration, Massey says. Over decades, that has contributed to a large increase in America's population diversity: According to the U.S. Census, now about 38 percent of U.S. residents are Hispanic, black, Asian or another minority group.

So while this year’s presidential candidates sculpt their talking points on immigration – or describe the walls they would build along the borders – American politics is in the midst of a sea change decades in the making, thanks in part to U.S. immigration policy.

The growing diversity of the voting population is affecting the outcome in political races – and the beneficiaries so far have tended to be Democratic candidates. For instance, 2012 election data shows that Republican Mitt Romney failed to attract voters from across the spectrum and it cost him the White House.

“In 1988, George Bush won 59 percent of the white vote, which translated into 426 electoral votes (and four years in the White House),” conservative columnist George Will wrote in a recent article. “Twenty-four years later, Mitt Romney won 59 percent of the white vote and just 206 electoral votes.” Romney, Will wrote, got just 17 percent of the minority vote.

If the past is any indication, these trends could become a problem for the Republicans. “In 2014, less than 50 percent of births were (non-Hispanic) whites,” says Massey. “That’s the future.”

Massey’s interest in immigration is part of a broader focus on economic stratification and inequality. As such, his work deals with a variety of issues involving race and ethnicity. A recent paper, for instance, dealt with the underlying issues that ignited racial violence in Ferguson, Missouri.

His interest in these subjects began in the turbulent 1960s in his hometown of Olympia, a city that reflected the racial stratification of American society. “While I was in junior high school, the first black family moved into Olympia. Before that, the only black person was a blind man who lived in a downtown hotel and made a living tuning pianos.” But Massey had only to pick up a newspaper or turn on the television news to see another America, as riots and the struggles of the civil rights movement played out across the country.

After graduating from Western with a Bachelor of Arts and three majors – sociology-anthropology, psychology, and Spanish – he earned his master’s and Ph.D. in sociology at Princeton, then began a long academic career that included first-hand research into immigration from Mexico. “Official data on illegal immigration isn’t very good,” he says. “So I designed surveys to collect data. I’ve been working in Mexico since 1982.” Every year, his survey teams go into a different set of Mexican communities to look at migration patterns. Then his teams go to the U.S. cities where the migrants have moved. This work, combined with other data sources, allows Massey to track the ebb and flow of immigration to the U.S.

At one time, he says, the migrant relationship between the U.S. and Mexico was governed by a predictable process. Migrant farm workers came north to the U.S. legally during the growing season, then returned to Mexico when it ended. Back then, illegal immigration wasn’t even on the radar screen.

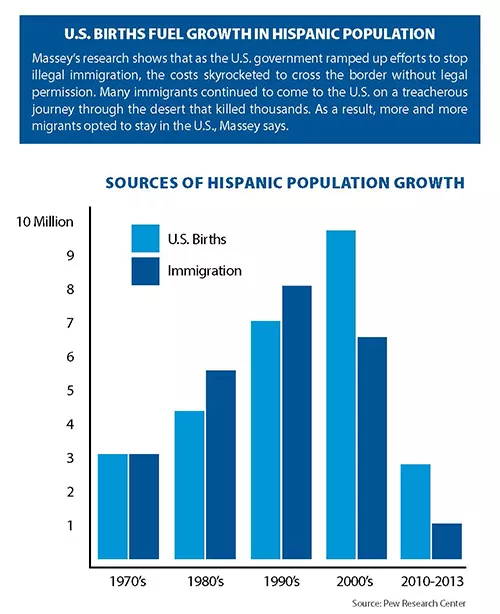

In the 1960s, Congress moved to ban the annual migrant influx. But the growers still needed labor and the Mexicans still needed the work. So the migrants came anyway – illegally. In response, the U.S. ramped up its efforts to stop them at traditional entry points such as San Diego and El Paso, Texas, says Massey.

The migrants countered by crossing the Sonoran Desert into Arizona. But this tactic was neither safe nor cheap. The average cost of an illegal border crossing jumped from around $500 to roughly $3,000, says Massey. Over time, thousands of migrants perished on their desert trek from exposure, thirst, drowning, homicide and other non-natural causes, federal data shows.

The combination of rising costs and danger eventually spurred many migrants to rethink their traditional pattern of coming to the U.S. for work and then going home. Instead, they began to stay.

“The end result was a doubling of the net rate of illegal migration and a sharp increase in undocumented population growth through the 1990s and into the new century,” Massey wrote in Daedalus, the Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. “In the course of two decades, the North American migration system was transformed from a circular flow of male migrant workers going to California and a few other states into a settled population of families living in all fifty states,” he wrote. The upshot: The number of residents living in the U.S. without legal permission soared from 1.9 million to 12 million in the two-decade period ending in 2008.

To counter this growth, the U.S. orchestrated a major increase in roundups and deportations. People responded by petitioning for U.S. citizenship to keep from being thrown out. The 2.4 million who have succeeded since 1990 were permitted under U.S. law to bring their spouses and minor children to the U.S. Steadily, this process has helped the number of new Latino citizens increase to the point that they are having a pronounced impact on the demographic makeup of the U.S. and its political system.

California is an example of the changes taking place. California was once a Red State that twice elected Republican Ronald Reagan as its governor – and president. It is now a Blue State in which some 15 million Hispanics (as identified by the census) and other minorities make up 61 percent of the population; the state has consistently voted Democratic in every presidential election since 1992.

The same factors may soon transform Texas, a Republican bastion and the nation’s second-most populous state. The state has more than 11 million Latinos and nearly 5 million other nonwhite Hispanic residents, who together now outnumber non- Hispanic whites by more than 4 million, according to 2015 estimates from the Texas Department of Health Services. “I think Texas will slip into the Democratic column in the next election or two,” says Massey. “When that happens, the Republicans will have very little chance at winning the presidency.”

But in the long-term, Massey predicts that U.S. politics will adjust to the population shifts, particularly if the rising tide of voters leaves one political party out in the cold. “The job description of a successful politician is winning elections,” says Massey. “And if they start to lose elections, they will have to change.”

He believes that time will resolve the illegal immigration issue as well, even if the U.S. doesn’t give legal status to the millions of people already here. “If the influx of illegal migrants stops, as it seems to have done, then eventually the illegal population will die out. And it will be replaced by their American-born children and their children’s children.

“Today there’s a reaction against this shift,” he says. “But ultimately, demography will have its way and the country will change.”

THE FACE OF A FAST-CHANGING NATION

The rise in the Latino population has propelled the U.S. toward the day when we will become a nation of minorities. Here are some facts from the U.S. census:

- Sometime in 2044, non-Hispanic white Americans will become another minority, just like Hispanics, Asians, African Americans and Native Americans. While non-Hispanic whites will still be the largest single group within the population, they will no longer constitute more than half the population.

- To get a glimpse of what America will look like then, just look at the makeup of America's children: Nearly one out of two is a member of (what is now) a minority group.

- By 2060, the demographic changes will be much more pronounced. Of a projected population of 417 million, the Census Bureau predicts there will be 182 million non-Hispanic whites, 119 million Hispanics, close to 75 million African-Americans, 49 million Asian-Americans, and more than 10 million Native Americans.

- Broken down by percentages, non-Hispanic whites will constitute about 44 percent of the population in 2060, Hispanics 29 percent, African-Americans 18 percent, and Native Americans 2.4 percent. Americans of mixed race will make up about 6 percent.

Source: Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014- 2060. U.S. Census Bureau March 2015.