Back when microbiologist Peter Greenberg’s (’70, Biology) baby daughter Barbara was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis in 1986, he had no plans to fight the disease in his own lab.

Being a worried dad was enough, he thought. Bringing the genetic lung disease to work with him would be too overwhelming.

Greenberg was happily working in what was then an obscure area of research: the social life of bacteria. He’s a pioneer in the discovery of quorum sensing, a mechanism in which bacteria accomplish something collectively that they cannot do alone.

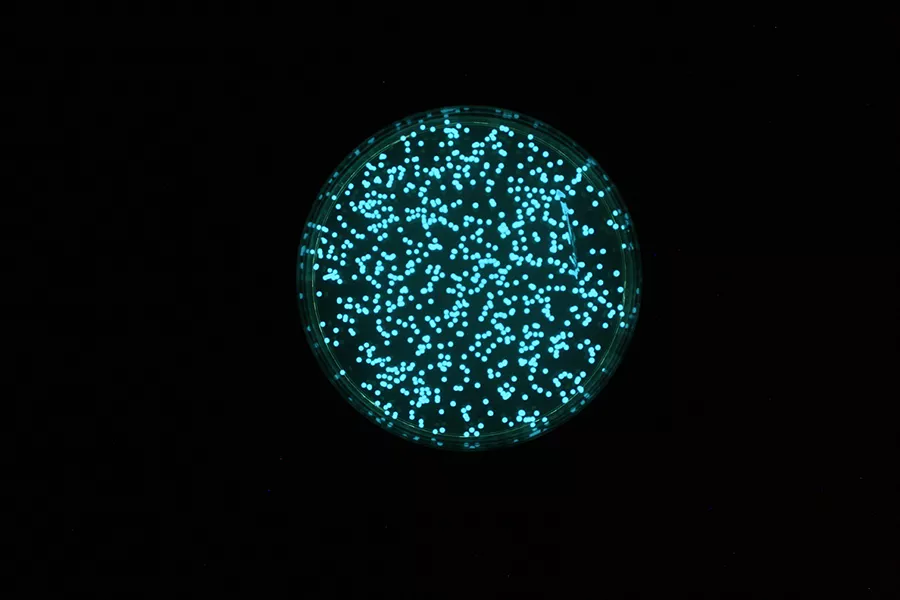

Greenberg first studied quorum sensing in luminescent bacteria, Vibrio fischeri, commonly found in sea creatures. “Somehow, they know when they’re in a crowd and they make light together,” Greenberg says. “A single bacterium can’t make enough light for anyone to see, but when they’re in a big group, they can.”

Greenberg and other scientists discovered in the ‘80s that bacteria communicate by releasing a chemical: When the concentration of the chemical rises, the lights go on.

“People said, ‘That’s interesting, but so what?’” remembers Greenberg, now a microbiologist at the University of Washington and a 2010 WWU Distinguished Alumnus. “But it turns out that what we’ve observed in these marine bacteria has been observed in lots of other bacteria. In fact, there are a lot of human pathogens that make those signals.”

Including the most common pathogen in the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis. When a colleague told Greenberg the CF pathogen Pseudomonas had genes similar to those that control light production in the luminescent bacteria, Greenberg’s research took on a new focus – and more scientists began to pay attention.

In September, Greenberg won the prestigious 2015 Shaw Prize in Life Science and Medicine with Princeton University microbiologist Bonnie Bassler. Greenberg and Bassler, chair of Princeton’s Department of Molecular Biology, will divide the $1 million award.

The international award was established in 2002 by the Hong Kong-based Shaw Foundation to promote worldwide scientific research. Many Shaw laureates have gone on to win the Nobel Prize.

Today, many researchers are competing to make drugs that target quorum sensing in the fight against disease, Greenberg says. And doctors already fight some nasty infections with drugs that attack communities of bacteria called biofilms, another offshoot of his work.

One of those drugs helped Greenberg’s now-adult daughter Barbara fight a CF-related infection earlier this year, her worried dad thankful for the help.