In the 28 years since he lost his son in an infamous Jack in the Box E. coli outbreak, no one could blame Darin Detwiler, ’97, B.A., history, if he had let bitterness consume him, cursed the government and food industry, and chosen to disappear.

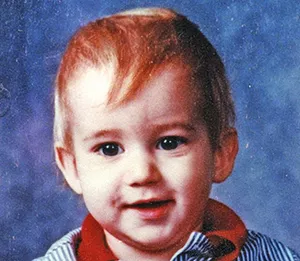

Sixteen-month-old Riley, who had just taken his first steps the week before, never ate a hamburger. He got sick at daycare from another child who had eaten the contaminated meat at a Bellingham fast-food restaurant.

The 1993 outbreak, which poisoned more than 700 people, made national news. It also made hamburgers suddenly scary. Riley was one of four children who died. Airlifted from Bellingham to a Seattle hospital, Riley was gone in a matter of weeks, leaving behind his dad, mom and a 9-year-old brother.

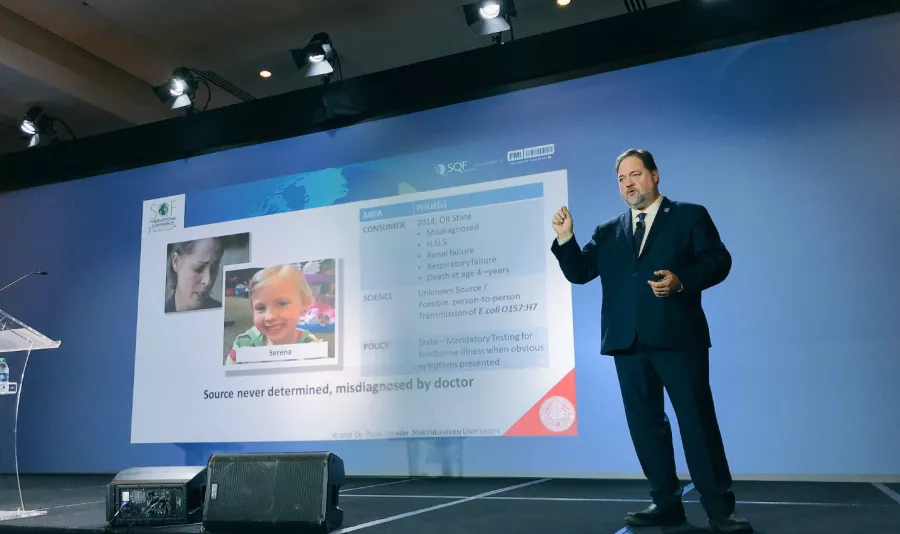

Instead of hiding, Detwiler immersed himself in the food-safety industry. Colleagues have described him as courageous, even a hero. He has a doctorate in food law and policy and is an internationally known expert in food safety. A professor for Boston’s Northeastern University College of Professional Studies, he teaches about food regulations, writes about food safety reform and food security for industry journals and works as an education consultant and victim’s advocate. He has worked with national agencies, U.S. legislators and is a sought-after speaker in the food industry. He has written two books, contributed to many others and has a TEDx talk.

“Nothing I do will ever bring back my son,” he says. “But everything I do allows me to grow as an individual… (and) also, in a way, continue to be a father to my son.”

The day after Riley’s death, President Bill Clinton called from Air Force One, asking how he could help. A grieving Detwiler told the president that consumers should be protected. At the time, “I honestly thought food safety was something the government would take care of, that we wouldn’t see this year after year.”

Channeling grief into a degree

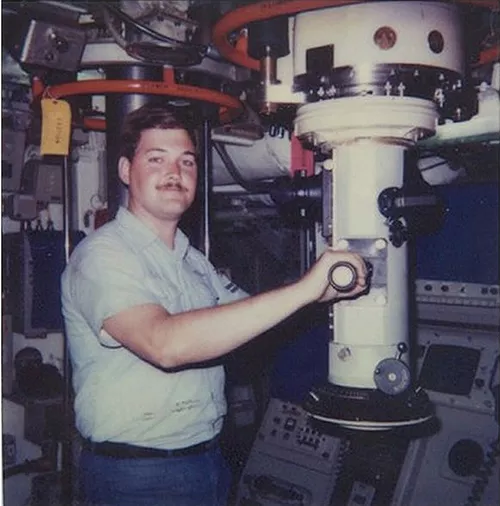

After high school in Moorpark, California, Detwiler graduated from the U.S. Navy’s elite Nuclear Power School, then operated a submarine nuclear propulsion plant off the West Coast. Having spent time at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard prior to completing his service in Hawaii, he moved to Bellingham in 1992, where he entered the naval reserves only a few months before Riley got sick.

Before the outbreak, “like most 24-year-olds, I thought I was immortal. After my work on a nuclear reactor, I thought I was smart—but I had no awareness of E. coli,” he says.

Detwiler channeled his grief into academia, enrolling in Whatcom Community College, then Western Washington University. At 25, while still a Western student, he wrote an op-ed for the New York Times headlined “Tragedy Wasn’t Enough.” He appeared on Good Morning America, Phil Donahue and CNN, and spoke to members of Congress.

After completing his bachelor’s degree, Detwiler continued at Western to earn his certificate in teaching, then went on to teach in local schools for 16 years, including high school history and social studies, math, science, forensic science and biotechnology. He even got FDA-certified as a food science educator and was appointed to serve two terms as a special advisor to the USDA while still teaching high school.

“No one trains people how to deal with the loss of a child,” he says in a phone call from Long Beach, California, where he recently moved to teach at one of Northeastern’s branch campuses. “We don’t take that class in high school. But going to Western Washington University was one of the best decisions I made in terms of … becoming part of a learning community” at a time when he was unsure of his life’s path. He says he believes it’s why he began and continues to teach. “I was definitely shaped by what I experienced at Western.”

Today, food recalls and Salmonella outbreaks in produce and at popular eateries like Chipotle are a part of life. So are books, movies and documentaries dealing with the food industry. Yet before 1993, food safety culture did not really exist in the minds of most Americans.

After, the innocuous fast-food hamburger became linked to a frightening pathogen most U.S. consumers had never heard of: E. coli. Common to humans and usually harmless, poisonous strains emerged with the meat industry practice of raising cows crammed together in feed lots, where fecal matter can contaminate meat. The beef industry—and Americans’ confidence in their food supply— would never be the same.

By 1994, the strain of E. coli that killed Riley had been declared an adulterant— meat that contained it could not pass USDA inspection. In the past two decades, E. coli cases linked to hamburger have declined dramatically. Food thermometers and cooking temperature charts (the USDA’s magic number for ground beef: 160 degrees Fahrenheit) are becoming more common in household kitchens, and restaurant restrooms are required to post hand-washing requirements. The industry is still dealing with major E. coli outbreaks, but also with other pathogens and other foods. The new scourge: Salmonella, with outbreaks in products like leafy greens, peanut butter and imported food.

“The skew has changed. Frankly, Darin had a role in that,” says Bainbridge Island attorney Bill Marler, who in 1998 co-founded a firm devoted exclusively to food safety cases. “There were a lot of players in that. What Darin has brought to the table is a real-world example of a family that was tragically impacted by food poisoning.”

Detwiler’s advocacy has taken its toll. He and Riley’s mom stayed together for 20 years after their son’s death but then split. Detwiler recently remarried; he has two sons and one stepson, all adults. He has sought counseling as he’s still sorting through the collateral damage from experiencing a parent’s worst nightmare —while reliving it to prevent others from that same heartbreak.

At conventions and presentations, workshops and federal hearings, Detwiler recounts the excruciating details: His kidneys failing, Riley calling for a bottle he couldn’t have; his little-boy body dwarfed by tubes and wires; and seeing him “in what looked like, to me, the world’s smallest white coffin.” He tells about his son’s death to open the door for others. “That is perhaps the number one way I can contribute,” Detwiler says. “Not by dumping my son’s story on them, but by building on my son’s story to paint a picture of why we need to do this, today.”

Mid-career shift

Soft-spoken and patient, Detwiler might still be a high school teacher if not for the day when TV news came to his Redmond classroom on the 20-year anniversary of Riley’s death. Despite his years of food safety advocacy and work with the USDA, he had never told his students about his family’s loss. After an interviewer forced his hand, one student raised hers.

“ ’Mr. D, if this is still an issue we have to deal with and you’ve been working on it all this time, why are you still a history teacher?’” he remembers. “I submitted my papers to resign at end of that school year.”

Newly single with grown children, Detwiler moved to Boston. He started teaching food policy at Northeastern while studying for his doctorate and traveling with the FDA for hearings on food safety. From 2014-2016, he was on the road so much he needed a spreadsheet to keep track. The day after defending his thesis, he was hired full-time as a professor, where he could not only teach his passion but pay the bills—he’s still paying off student loans.

“To see Darin transform himself and commit to these issues and just remain focused, remain determined and undeterred… it’s absolutely inspiring,” says Brian Ronholm, FDA undersecretary of food safety under President Obama and currently Consumer Reports’ food policy director.

Food culture is now mainstream, from Anthony Bourdain to Morgan Spurlock’s “Supersize Me.” But in 1993, Detwiler was invited to work on a TV movie about Riley’s death that never got made. “Not enough sex and violence,” Detwiler says network executives told him. Now, Netflix is shooting a documentary based on the book, “Poisoned,” about the 1993 outbreak. Food safety attorney Bill Marler figures prominently, and Detwiler was hired as a technical consultant.

“People might not even realize the impact he’s had because he’s been working behind the scenes, working with the regulators, working with the industry, working with victims of foodborne illness,” says former student Adam Friedlander, now a food safety manager at the Food Marketing Institute in D.C. “Darin is a hero within the food system.”

Mary Heersink nearly lost her son the year before the deadly 1993 E. coli outbreak. A board member for the advocacy group Stop Foodborne Illness, she says Detwiler last year helped produce a guide for parents whose kids got sick or died from food poisoning. “Darin was so helpful…honest, so transparent, so emotionally giving,” she says.

Detwiler didn’t eat red meat for years, but “I can’t be the boy in the plastic bubble,” he says. “I still have to eat.” He avoids cantaloupe, sprouts (“You can’t clean it,” he says), and bagged lettuce because you can’t trace it to one supplier.

Detwiler does most of the shopping and cleaning of food in his household. At an unfamiliar restaurant, he first visits their restroom. If it’s dirty, he’ll gather his guests and walk out. A professional perk? “I have the executive leadership on speed dial,” including Pepsi, The Cheesecake Factory, Wendy’s, Costco and Amy’s Kitchen.

Despite more awareness and scrutiny, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates 48 million people suffer foodborne diseases annually, 128,000 are hospitalized and 3,000 die.

“I even got a food-borne illness (Salmonella) at a food safety conference,” Detwiler says. “We’re all vulnerable.”

The growth of anti-science, anti-regulation groups, who insist on people’s rights to drink unpasteurized milk and eat undercooked steak, for example, doesn’t help. Obama’s 2011 signing of the Food Safety Modernization Act gave the FDA more authority, including long-sought mandatory recall power.

Meanwhile, Detwiler keeps teaching, talking and plugging away. A current project: working with the foodborne illness investigation industry on a program that can track food purchases and notify individuals through text or email when there’s a recall. (Consumer participation would be voluntary.) “I want to make sure the benefit is for the consumer,” he says.

Losing Riley shaped him but, Detwiler insists, does not define him. “I truly believe I’ve found a voice,” he says. “For every bad actor, if you will, when it comes to food safety, there are hundreds on the other end of the spectrum. My work has been, to some degree, my greatest therapy.”