Radioactivity

U.S. Marine veteran Chris Brown (’12, Human Services) says his burden from three deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan is like a bag of rocks. The rocks represent the injuries, physical and mental, he and his fellow Marines suffered, and the guilt that he made it back home when 41 of his friends never did.

He carries this symbolic burden over his shoulder wherever he goes and, sometimes, he just wants to set it down.

“The tough part,” he writes, “I’m afraid to lose those rocks. I’m afraid to lose them because of what they have done to shape my character and who I am as a man.”

But by sharing his experiences, Brown feels as though he can pass on some of those rocks for safekeeping, easing his burden.

He’s also taken a few of those rocks and planted them in the earth. What’s growing there now will help many other veterans ease their own burdens.

Brown is founder and director of Growing Veterans, an organization combining sustainable farming with veteran reintegration.

The concept grew out of his experiences studying Human Services at Western while working in Western’s Veteran’s Services office through the VetCorps program. He and some of the “regulars” from the veterans office, many of them students at Huxley College of the Environment, often discussed agriculture and food systems.

Brown saw that sustainable agriculture practices could use support, as could veterans transitioning back into civilian life. Together, the two created some very powerful outcomes, he thought.

Growing Veterans was also a way to support himself as he works through his own struggles as a combat veteran.

“I wanted to focus my learning on veterans’ issues in an attempt to both understand myself better but also to enter a career centered around helping veterans,” Brown says.

More personally, Brown says, his work is “an attempt to justify the guilt that I carried about the guys who never made it home.”

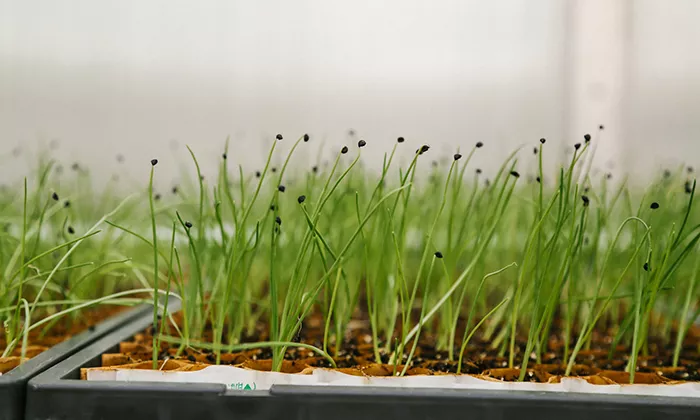

On a sunny, crisp March morning, Brown gives a tour of the Growing Veterans farm in rural Whatcom County. Beds of kale and leeks have wintered over, and a new field on the southern end of the property is freshly tilled. One greenhouse is already filled with starts for the planting season, and the other greenhouse is nearly ready for tomatoes, basil and peppers to be sold at farmer’s markets outside Veterans Affairs hospitals.

On this day, a handful of people are working on the farm. Outreach Coordinator and Market Manager Matt Aamot, an Army veteran of Kuwait and Bosnia, is showing around new employee Dan Robinson. It is Robinson’s first day as the field manager, recruited from a veteran-farming program in Colorado.

Meanwhile, Billy Pacaccio is working on the junction box in the barn. Pacaccio was a Navy veteran and a Whatcom Community College student when he joined Growing Veterans in its second year. He says his job is not just helping to manage the farm, but building a community in which his fellow veterans, with all kinds of backgrounds and experiences, come together around a goal.

“They found the earth in common,” Pacaccio says, “and from there they prospered from it.”

Growing Veterans has five full-time paid staff members and four part-time employees, all but one a veteran. Three more veterans also work for Growing Veterans through AmeriCorps.

In addition to paid staff, volunteers – 370 last year alone – help in the field or greenhouse, or sell produce at farmers markets. Others help with peer support or community outreach or with tasks such as grant writing and advising.

Brown, 28, grew up King County and didn’t have a background in farming, so when he decided to start a veterans’ farming group he first needed some basic training. He turned to Growing Washington, an Everson-based nonprofit supporting the growth of sustainable agriculture. Brown was hired on as a farmhand, working 20 hours a week to learn all the facets of farming, from planting to delivery.

He spent another 20 volunteer hours a week developing the Growing Veterans concept. By the time the 2013 growing season rolled around, Growing Washington had helped Brown and Growing Veterans secure a three-acre farm in Whatcom County that once belonged to the Bellingham Food Bank.

Then Brown started getting the word out, and an initial crew of four veterans got involved. Word started to spread, and the first season saw more than 100 volunteers, veteran and civilian, come lend a hand on the farm.

“I’ve gone with the motto, ‘If you build it they will come,’” says Brown, who has submitted the IRS paperwork for Growing Veterans to become an independent nonprofit organization. “We weren’t expecting it to happen so fast.”

Growing Veterans sells its produce at weekly farmers markets at the VA hospitals in Seattle and Lakewood. Some local grocers have expressed interest in selling as well, which may be possible as the operation grows, Brown says. He would also like to open a commercial kitchen to create “value-added” products from the produce, and create more jobs for veterans.

But Brown’s plans include much more than employment: One of his long-term goals, to develop peer-to-peer support for veterans, took a giant step forward this winter when Growing Veterans signed a lease on a 40-acre property on the Skagit- Snohomish County line. The land, owned by a Vietnam veteran, will allow Growing Veterans to plant some perennial crops such as blueberries to supplement their farmers markets as well as provide a space for retreats and reflection at the home located there.

“It’s in a more rural setting that will lend itself to therapeutic activities for our peer support programming,” Brown says. Nationally, an average of 18 to 22 veterans a day commit suicide, and Brown is hopeful Growing Veterans’ peer support training, with a focus on suicide prevention, will be in place by the end of the year.

Brown and two other peer mentors were recently certified through ASIST, a suicide-intervention training program. Brown’s goal is to get all peer mentors certified, and have some mentors certified as trainers so they can bring suicide intervention training to others in the community.

So far, the peer support element of Growing Veterans has been relatively informal, but intentionally so, Brown says. Often, veterans struggle to reach out for help because military culture traditionally viewed seeking help for mental health issues as a sign of weakness. By avoiding language around “getting help” and focusing on building camaraderie and community, Brown feels veterans have been more comfortable and willing to participate in what he calls an innovative peer-support program.

“The reason I can confidently say it is innovative is because it’s not being designed by doctors; it’s being designed by the veterans who are involved,” Brown says, adding that the vets are also consulting with mental health counselors along the way.

Brown estimates Growing Veterans’ peer-to-peer support will reach at least 50 veterans this year; in the long term he hopes to help thousands.

Coming to the farm benefits veterans in numerous ways, Brown says. “They’re talking about similar experiences, realizing they’re not alone in this struggle to reintegrate, and they’re sharing real, tangible supports with each other.”

Another important goal of Growing Veterans, Brown says, is to broaden interaction between veterans and civilians. This facet of Growing Veterans is unique, he says, something he has not seen in other veteran farming projects across the country.

And when the greater community gets involved, the veterans get a different kind of support: understanding.

Bridging the gap between veterans and civilians is vitally important as servicemen and -women reintegrate into daily life outside the military. Brown suggests that simply inviting a veteran to tell his or her story, listening with openness and respect, offers some of the greatest help a veteran can receive.

“Not only are you helping yourself have a better understanding of the veteran experience,” Brown says, “but also opening the door for a veteran to heal.”

Brown has tapped into Western’s resources to help establish Growing Veterans. Interns, working with the Center for Service Learning, have helped write grants, plan events, design websites and more.

And English Professor Emeritus Bill Smith has been a core volunteer, helping the organization develop its grant-writing system.

“He’s like our guardian angel,” Brown says.