Imagine following the traditional hunting trails of your ancestors while hearing the animal migration stories of your people in your native language — a language that hasn’t been taught since your grandparents’ generation.

Caskey Russell is using virtual reality to offer this experience to generations of Indigenous people who otherwise never would have had the opportunity. The dean of Western’s Fairhaven College of Interdisciplinary Studies, Russell published new research in March 2023 in the Journal of Native American and Indigenous Studies Association on how virtual reality could be used to revitalize dying languages.

According to the United Nations, 96% of the world’s languages are spoken by only 3% of the population. And while Indigenous people only make up 6% of the world’s population, they account for over 4,000 of the 6,700 languages recorded so far. Furthermore, a report by the UN in 2019 found that a language was going extinct every two weeks — which means that more than 100 additional languages have gone extinct since that study came out.

Back in 2017, when Russell was the chair of American Indian Studies at the University of Wyoming, he saw the potential for VR while working with Wyoming graduate student Phineas Kelly on an augmented reality program aimed at teaching the Arapaho language.

Like the popular augmented reality game Pokémon Go, Kelly’s program superimposed animated graphics and sounds on the landscape as viewed on the screens of users’ mobile devices at specific locations at the Wyoming campus.

After the success at Wyoming, Russell saw the opportunity to go further and become more immersive. Kelly and Russell worked with the elders of the Arapaho tribe to record a song and story that they then placed within a fully immersive traditional Arapaho gathering space just outside of Laramie, Wyoming called Bito’o’wo. The program also filled the space with interactive images of cultural items.

“Arapaho community is very close knit, multiple generations living together, and they saw what we were doing,” said Russell as he reflected on the results of their efforts over the years. “They find tech beneficial when it can promote the culture. It matched with their grandkids’ and great-grandkids’ interest in computers and video games in particular.”

Russell is himself a member of the Tlingit tribe of Alaska— a relationship that deepened during his graduate studies at Western and at the University of Oregon. He yearned to further his own cultural connections and jumped into researching immersive language tools such as virtual reality.

“I wanted the languages at least for the tribes in Wyoming to be offered in our curriculum,” Russell said. “But also important to me was the notion that, if this works, maybe I can use this to aid me in my own language acquisition.”

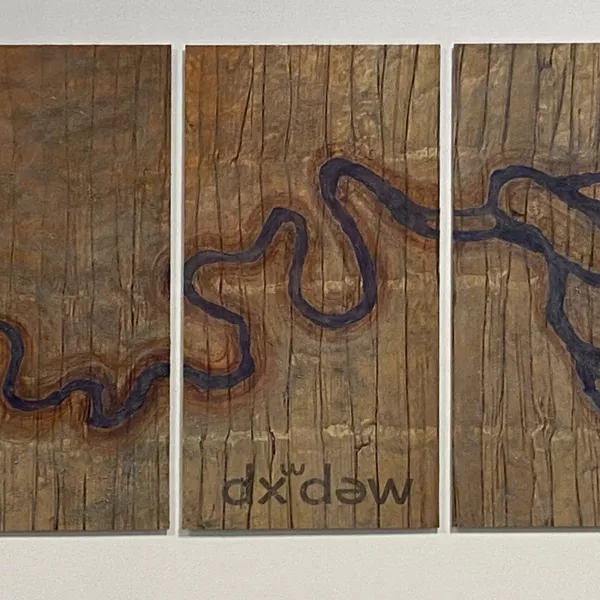

Russell worked with Kelly for six years on these AR and VR projects between 2017 and 2022, mapping traditional locations using video cameras and then working with the Arapaho elders to record the language and stories that went along with the locations.

“It was a lot of fun hiking up to some of these areas,” Russell said. He traveled to the Never Summer mountains in Colorado and Elk Mountain in Wyoming, and it “was really cool to go to and film.”

These experiences that Russell’s team was able to capture create learning experiences that would be impossible without technology. For the price and time of one team going on these excursions to these locations, now an infinite number of students can replicate the trip all from the classroom.

“We're in the testing phase, and now the VR is in the Northern Arapaho Immersion Preschool,” Russell said. “It'll be interesting to see the feedback from the language speakers and the elders. Is it working? [Are they] becoming more fluent in Arapaho?”

With the alarming rate at which languages are being lost, the importance of efforts like Russell’s is intensified as they not only compete against the clock of extinction but also represent potentially the last line of defense in revitalizing these endangered languages.

For example, of the roughly 30,000 Tlingit members, there are just under 100 fluent speakers left. Russell’s grandmother passed away in 1997, beyond the loss of a beloved family member it was also the loss of a tangible way to learn his native language.

“My grandmother was the last fluent Tlingit speaker in our family. My mom and I didn't learn it, and I tried in graduate school,” Russell said, gesturing to the wall of books in front of him, pointing out several on the Tlingit language, dictionaries, and introductory reference material. “It is a difficult language.”

VR allows us to engage in learning a language how we learn our first language — observing and engaging with our surroundings while hearing our peers and elders speaking.

Russell has plans to enlist VR to help more people learn the Tlingit language, too.

“The goal for me would be ‘Zelda’ in Tlingit, a video game — fully immersive VR video game — set maybe 500 years ago up in native Alaska,” Russell said. “You have to enter a village and maybe from oral tradition take a quest or you know fight a traditional monster.”

Russell beamed with excitement as he discussed his many goals and parameters for the final product of this fully immersive language program: A game that would not only be entertaining but capable of dialing in a person’s language comprehension in a way that it could slowly intensify until they were experiencing the program entirely in Tlingit.

“I've kind of put it on hold because of the deanship but I'm still searching for ways to connect with the tech around here and the tribes and I still have that as a goal,” Russell said.

Russell’s goals with revitalizing these Indigenous languages go beyond just offering programs to the respective tribes involved. He believes that the mass appeal of fully immersive language programs could be a way to bring these sorts of languages to the broader community. During his time on the project, he said that roughly 50% of participants were non-Native.

“I think many students beyond just Native students would be interested in learning an Indigenous language,” he said. “It's just never been on offer.”

He added that part of the cultural genocide of the 1800s was the active effort to seek out and eradicate any programs that did offer to teach these native languages.

Russell said he would love to see an immersive language program formed at Western and the surrounding high schools.

“I would love to see Western offer local native languages,” Russell said. “In those languages, you're going to get the history of this area, history of the Salish Sea, history of the tribes — history of a lot of stuff, a lot of cultural stuff. That could be enlightening to Native students and non-native students. Offering languages in high schools and universities from local tribes will go a long way in telling these tribes ‘Yes, you're welcome here, and you have a place at this university.’”