When 12-year-old Will Taylor first felt attracted to other boys, it was thrilling and perilous all at once.

“Feeling that rush that should be joyful was immediately turned into a negative,” says Taylor, ‘05, B.A., Fairhaven interdisciplinary concentration. “It was 1994 and it wasn’t safe to feel that way.”

During his childhood, Taylor didn’t see LGBTQ+ people included authentically in the books he read or television he watched, nor did he have someone he felt safe talking to about his feelings. “I’d never even been shown what it means to be gay,” he says. “When I had these really big feelings for the first time, I immediately suppressed them because of the fear.”

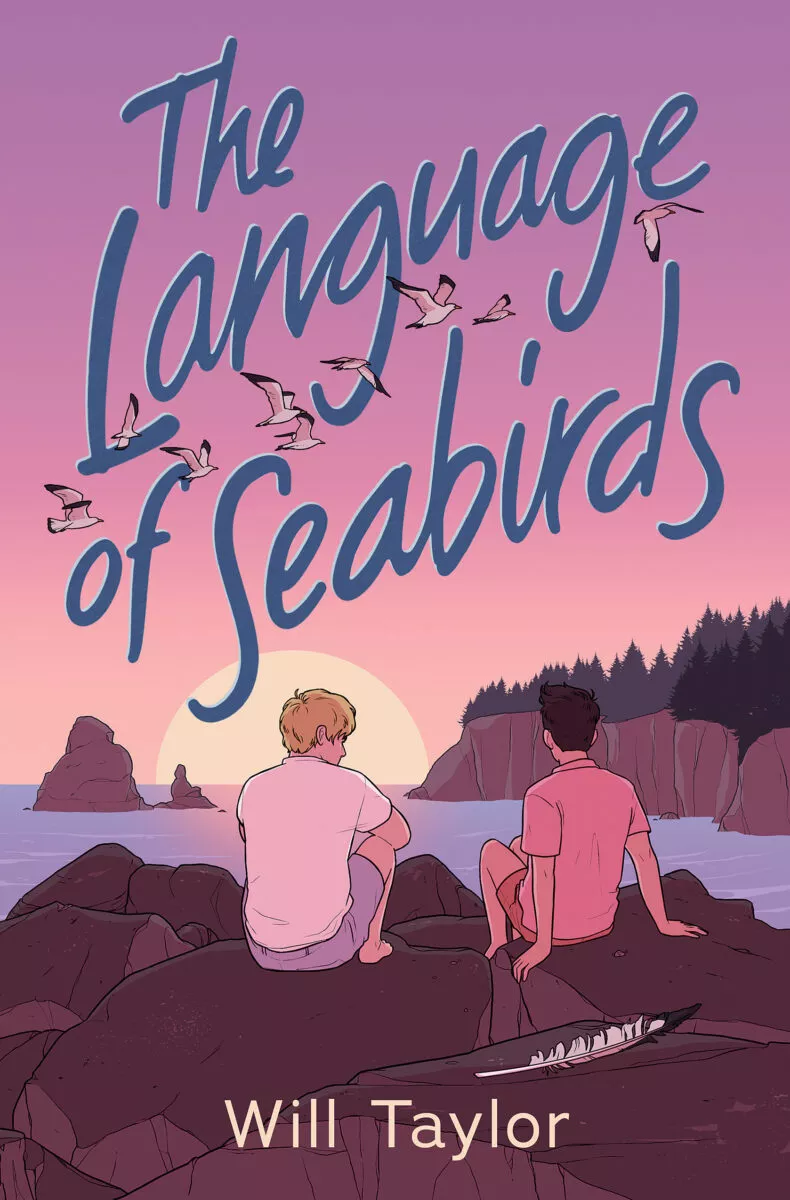

At age 40, Taylor wrote “The Language of Seabirds.” Published in July by Scholastic, it is one of the small but growing examples of books for and about LGBTQ+ youth.

The main character, 12-year-old Jeremy, is attracted to a boy named Evan during a vacation to the Oregon Coast with his newly divorced dad. Throughout his two weeks at the beach, Jeremy overcomes his uncertainty and fear to develop an ever-deepening relationship with Evan.

“I really wanted to create a book where a 12-year-old had the exact same experience I had,” Taylor says, “but he gets to go a different direction.”

Jeremy and Evan’s relationship blossoms as they create a coded language based on the names of seabirds, inspired by a field guide Jeremy finds in the vacation home. It starts with marbled murrelet, which means “friends,” peaks with Cassin’s auklet for “us,” and ends with curlew, which symbolizes “goodbye.”

This code—and the empowerment Jeremy and Evan found in its development—is so central to the story that Taylor dedicated the book to “every kid who’s had to speak in code.”

“Jeremy is a lot braver than I was,” Taylor says. “He was way more willing to take risks.”

WWU Librarian Sylvia Tag says that children’s literature serves as a mirror, a window, and a sliding glass door, a concept coined by Rudine Sims Bishop, a trailblazer in the field of multicultural children’s literature.

When a child sees themselves in the characters of a book, Tag says, that story becomes a mirror. When children read about characters different from them, they can develop a sense of empathy for a wide array of identities and the book becomes a window. When the mirror and window change a child’s perspective, the book becomes a door to a more inclusive world.

“It’s so important to everyone’s healthy development to grow up with books that they can see themself in and that expand one’s understanding beyond only the self, their immediate family, and their closest peers,” says Western’s Litav Langley, assistant vice president of Access, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion and previously director of LGBTQ+ Western.

“Seabirds” is a bit of a departure for Taylor, an established children’s author whose four other works include middle-grade buddy comedies like “Maggie and Abby’s Neverending Pillow Fort,” and the girl-meets-celebrity-poodle tale of “Catch That Dog.”

No time for bullies

While completing his concentration in Sacred Architecture at Fairhaven College of Interdisciplinary Studies, Taylor took two writing classes with published authors: a poetry class with retired professor Mary Cornish and a short story class with former WWU faculty member Greta Gaard.

“Both were more impactful than I properly understood at the time, and they definitely bookended my time at Western,” Taylor says.

Taylor uses his WWU-inspired zeal for creative writing to build an environment in “Seabirds” where Jeremy and Evan face conflict, but not the bullying and trauma that is prevalent in LGBTQ+ literature.

“Emphasizing bullying and difficulty fitting into straight society is still centering heterosexual narratives—it’s about them having trouble with gay people and how gay people suffer after that,” Taylor says. “I decided, ‘I’m not going to give them the time. This is my world. I’m not going to give them power here.’”

Instead, the conflict comes from Jeremy’s hesitation to tell his dad about his feelings for another boy. His father’s frustration grows as Jeremy chooses time with Evan over him.

This tension builds until Jeremy’s dad finally realizes his son’s relationship with Evan is much more than a friendship. Taylor says the moment in the book where Jeremy comes out to his father was so powerful it brought one early reader to tears.

“I wrote it for 12-year-old me,” Taylor says, “because I know that 12-year-old me needed it so deeply.”

Unfortunately, LGBTQ+ representation in children’s books is sorely lacking.

“Queer books are having a bit of a boom moment, but only in comparison to their almost total absence on library and bookstore shelves before,” Taylor says. “It’s pretty grim how far publishing has to go to reach even mild equity.”

Meanwhile, books with LGBTQ+ and ethnically diverse characters are being removed from school libraries across the country. PEN America counted 1,145 titles by 874 different authors that were banned in 86 school districts during the past year alone.

This kind of censorship can have dire consequences, according to Taylor, noting that the already “incredibly high” rates of suicide among LGBTQ+ youth rose during the pandemic.

“Queer youth are so often trapped at home with family situations where they’re not safe, where they’re separated from peer access, they’re being bullied online,” says Taylor. “It’s very, very grim for Queer youth right now in this country, especially with the targeted book bans and major political parties trying to remove access to books like this that can literally save lives.”

“Seabirds” has not been targeted or banned yet, but it could as it becomes more well known, says Richard Price, ‘03, B.A., political science and history. Price is associate professor of political science at Weber State University whose blog “Adventures in Censorship” explores book challenges in school libraries.

“Just in terms of the description, (‘Seabirds’) definitely hits all the things that make it a target because it’s Queer-affirming,” they say.

Activist groups that advocate book banning often react to one or two sentences or pages that go viral on social media, Price says. Something as minor as a same-sex couple holding hands can be enough for them to start pressuring schools to ban it, they say.

Some of this may be rooted in inaccurate assumptions of what LGBTQ+ literature represents, says Langley.

“There is often a problematic misrepresentation that talking about LGBTQ+ folks, especially in lower grades, means teaching about sex. In fact, it simply means talking about people who are in our families and school communities. It’s part of a broader, harmful trope that hypersexualizes LGBTQ+ folks.”

Fighting the bans

Recently, groups of parents and community members have been showing up to school board meetings and emailing school administrators to prevent LGBTQ+ inclusive literature from being banned, Price says. Examples include the national group Red, Wine, and Blue, and localized movements such as the Florida Right to Read Committee.

But people don’t have to wait until inclusive literature for kids is under attack before taking action, Langley says. People can partner with school officials and teachers to help make sure that inclusive curriculums and literature are maintained and ask questions when schools aren’t being inclusive.

Publishing companies can also push back against book challenges. For instance, Scholastic has a department to help authors with challenges against their books, Taylor says.

“Obviously when it comes to state laws there is only so much they can do, but if and when I do get pushback of a more substantial nature, I know that they will have my back,” he says.

School librarians can also be leaders in stemming the tide of book bans, says Tag, by developing a protocol for fairly and justly evaluating whether a book should be removed from the school’s collection.

“These documents are in place so that when challenges come up, there’s a rationale that people aren’t thinking about for the first time,” Tag says. “There are thoughtful people in those states and there are advocates for reading and for kids, but they’re being overwhelmed by the politics of it.”

Taylor says he saw the effect of these politics firsthand when a teacher asked him to come talk to their class about “Catch That Dog” but not mentioning “Seabirds” in the request, even though the books were released only three weeks apart. Whether the teacher didn’t want their students to know about the book, or was afraid of the political backlash, the result was the same.

“That felt very insidious and very hard to fight because if people aren’t coming right out and telling me ‘We pulled your book, we banned your book, we’re not buying your book because it’s Queer,’ I have no way of reacting or fighting back,” Taylor says.

Despite this challenging climate for LGBTQ+ books, Taylor’s vision of a more inclusive world of children's literature remains.

“One of the goals many teachers, librarians, and authors share is that we want every single kid in every single school in America to have a book that reflects their experience available in their library,” Taylor says. “We’re not even slightly close to that happening at this point, but we are working on it.”